Many of our fears about growing old are exaggerated, writes LINDA GORDON. Mrs Abraham and George help her realise that.

Courage, my friends

|

April 18, 2015

THERE is a tendency towards the absolute when it comes to considering our old age: It will be ghastly; I will be forgotten; I will be dribbling at both ends; I would rather die. We imagine a place and time where who we are and how we live will count for nothing. This is not my first-hand experience in working with frail older people and those living with dementia. If anything, older old people are more abundant in their humanity – their humanness – than my peer group. In my experience of helping the vulnerable elderly I have come face to face with some of the funniest, bravest, saddest people I am likely to meet in my lifetime. Coping with this onslaught takes a toll but I feel privileged to have experienced the dying of the light along with them. We have to be able to overcome our instinct for disgust and denial at the way a life can go in order to appreciate the lessons of our elders. It may be a good moment in time for older baby boomers to consider the real situation for people in their 80s now, as opposed to the distorted picture we’ve come to rely on. In June 2013 there were 168,968 people living permanently in aged care homes in Australia. That figure represented about a quarter of the total population aged 85 years and over. Census and population research data also showed that two-thirds of older, old people, needing some measure of help with domestic and personal care, live in the community, and that living alone is the predominant arrangement. Clearly we are not all headed for the dreaded institution. Over the last decade there has been a reduction in the number of care homes but they are getting bigger, with most having more than 60 beds. I’m using the term care homes rather than aged care facilities as this latter seems such a bureaucratic dodge. What is a facility, anyway? It certainly doesn’t sound like anybody’s home. And home is where we want to be, overwhelmingly. This was made very clear to me when I began working for an inner-city council’s home and community care (HACC) service, in 2004. |

"How would I want to live?"

The Wintringham story “At every farm there was always a verandah at the big house where the boss lived. And the boss always had an old father who would sit on the verandah with a moth eaten old dog. They would sit together observing all the goings on. You’d give him cheek as you passed and he’d wave his stick at you. He wasn’t inside waiting to die and he wasn’t outside working, he was in between. He would give his opinions on the stock and do jobs like collecting the eggs. He wasn’t behind glass windows peering out. The verandahs gave him a space to be.”

Wintringham aged care and housing services CEO Bryan Lipmann is describing his design concept for a hostel called McLean Lodge. Built in Flemington in the early 1990s, it was designed around the needs of elderly homeless people. The verandahs became an integral part of the hostel’s design despite causing much hand wringing among the housing and aged care bureaucrats at the time. In 2011 Wintringham won Australia’s first UN Habitat Scroll of Honour Award, a prestigious human settlements accolade. Wintringham, with its social justice model of care to the fore, seems to have been able to keep a tight focus on the person in need, and not on the system. As author Elaine Farrelly describes it in her book The Wintringham Story, for Bryan Lipmann the most important question when planning care for the elderly homeless was, "How would I want to live?" |

I visited a list of people each week, helping them with domestic chores, showers, shopping and meal preparation. I had completed the required TAFE course and was continuing my studies in aged and dementia care. My regulars made the theory all too real.

Mrs Abrahams was not happy. She had been told by the last carer that her cat was dangerous and would have to go. It took a lot of polite cajoling to get her to answer the door on my first visit.

The issue, I discovered, was the cat’s litter tray. I was there to help Mrs Abrahams with her shower but what she most wanted was help with emptying the cat’s overflowing toilet. Mrs Abrahams could not bend or walk well but, oh, she loved that cat.

All it took for us to develop trust and a good working relationship was for me to empty the litter tray and put down clean newspaper each time I visited. Then she would happily let me help her get cleaned up and dressed for the day.

Reports of her being in danger from tripping over her cat or of infection from cat droppings threatened Mrs Abraham’s independence and, as she saw it, had her leaving her home and her beloved pet behind. She was feisty but with good reason.

I used to wonder if George got me mixed up with another sort of female from another sort of service. George was a bachelor in his 90s, polite and softly spoken but within minutes of my arrival to his tidy home he would be asking me to sit beside him, to stop cleaning and have a cup of tea, or putting his hand on my leg while I drove him to the shops.

He was lonely, isolated but fiercely independent. He had been refusing all home help and just muddling along. I can’t say that I always enjoyed George’s company but I would have a cup of tea with him when there was time, and I know he looked forward to this. When I left the council I think they tried to get a male carer to help George. I hope it worked.

How would George and Mrs Abrahams have coped with a move into a care home? What would they have thought of the daily enquiry about bowel movements, the surrender of privacy, and the mostly unintended, casual cruelty of institutional care?

I hear the complaint from within aged care that “it’s the system, there’s nothing we can do” but I’m not convinced. When I worked in aged care I was the system for the people I was there to help.

As soon as we shift our focus away from individual people, those fully formed and complicated human beings like George or Mrs Abrahams, and towards residents, or clients, or consumers of care, we are lost.

Training and education is important in community and health services but it does not stop abuse of our personhood, or guarantee our humanity will be honoured. Educated teachers, priests, the staff of care institutions at all levels commit all manner of abuse because the system, the institution, protects them.

But persist with the individual, refuse to think of “them”, and we can make a home away from home that might suit any one of us.

My wish list for aged care for the frail and vulnerable elderly, and for myself when the time comes, includes deinstitutionalised small communities centred on a garden, with more palliation and less intervention. I will want timely attention to relieve discomfort and pain but more than this I wish for kindness, humour and grace in my decline.

A former newspaper journalist, Linda Gordon has worked as a home and community care worker, personal care worker in residential aged care, teacher in aged care, and diversional therapist in dementia-specific care.

COMMENTS

April 23, 2015

Thank you, Linda. Your beautifully written, humane essay goes to the heart of the matter. But why, we need to ask ourselves, do so many homes not provide the ideal you describe? In my volunteering role I have seen some very sad situations over years, yet felt powerless to intervene, and guilty at not doing so.

Felicia Di Stefano, Glen Forbes

April 19, 2015

Thanks Linda Gordon for putting your "… wish list for aged care for the frail and vulnerable elderly" so clearly. Your list corresponds to my dream of care in my less able time down the track of life - though I fervently hope not to need it.

Sue Packham

Mrs Abrahams was not happy. She had been told by the last carer that her cat was dangerous and would have to go. It took a lot of polite cajoling to get her to answer the door on my first visit.

The issue, I discovered, was the cat’s litter tray. I was there to help Mrs Abrahams with her shower but what she most wanted was help with emptying the cat’s overflowing toilet. Mrs Abrahams could not bend or walk well but, oh, she loved that cat.

All it took for us to develop trust and a good working relationship was for me to empty the litter tray and put down clean newspaper each time I visited. Then she would happily let me help her get cleaned up and dressed for the day.

Reports of her being in danger from tripping over her cat or of infection from cat droppings threatened Mrs Abraham’s independence and, as she saw it, had her leaving her home and her beloved pet behind. She was feisty but with good reason.

I used to wonder if George got me mixed up with another sort of female from another sort of service. George was a bachelor in his 90s, polite and softly spoken but within minutes of my arrival to his tidy home he would be asking me to sit beside him, to stop cleaning and have a cup of tea, or putting his hand on my leg while I drove him to the shops.

He was lonely, isolated but fiercely independent. He had been refusing all home help and just muddling along. I can’t say that I always enjoyed George’s company but I would have a cup of tea with him when there was time, and I know he looked forward to this. When I left the council I think they tried to get a male carer to help George. I hope it worked.

How would George and Mrs Abrahams have coped with a move into a care home? What would they have thought of the daily enquiry about bowel movements, the surrender of privacy, and the mostly unintended, casual cruelty of institutional care?

I hear the complaint from within aged care that “it’s the system, there’s nothing we can do” but I’m not convinced. When I worked in aged care I was the system for the people I was there to help.

As soon as we shift our focus away from individual people, those fully formed and complicated human beings like George or Mrs Abrahams, and towards residents, or clients, or consumers of care, we are lost.

Training and education is important in community and health services but it does not stop abuse of our personhood, or guarantee our humanity will be honoured. Educated teachers, priests, the staff of care institutions at all levels commit all manner of abuse because the system, the institution, protects them.

But persist with the individual, refuse to think of “them”, and we can make a home away from home that might suit any one of us.

My wish list for aged care for the frail and vulnerable elderly, and for myself when the time comes, includes deinstitutionalised small communities centred on a garden, with more palliation and less intervention. I will want timely attention to relieve discomfort and pain but more than this I wish for kindness, humour and grace in my decline.

A former newspaper journalist, Linda Gordon has worked as a home and community care worker, personal care worker in residential aged care, teacher in aged care, and diversional therapist in dementia-specific care.

COMMENTS

April 23, 2015

Thank you, Linda. Your beautifully written, humane essay goes to the heart of the matter. But why, we need to ask ourselves, do so many homes not provide the ideal you describe? In my volunteering role I have seen some very sad situations over years, yet felt powerless to intervene, and guilty at not doing so.

Felicia Di Stefano, Glen Forbes

April 19, 2015

Thanks Linda Gordon for putting your "… wish list for aged care for the frail and vulnerable elderly" so clearly. Your list corresponds to my dream of care in my less able time down the track of life - though I fervently hope not to need it.

Sue Packham

When her mother could no longer manage at home, LINDA GORDON saw the good, the bad and the indifferent sides of aged care.

Maria’s story

Maria Cawcutt, Europe, 1950s

Maria Cawcutt, Europe, 1950s

March 21, 2015

MY MOTHER died a little over five years ago of pancreatic cancer and with Alzheimer's disease. She was in her 90th year. Her cancer was advanced at diagnosis and speedy in its progress; from confirmed to cremated in about six weeks.

This was all in stark contrast to the progress of her unique experience of dementia, where the signs and symptoms emerged more than 10 years before her death.

These years were confounding and frustrating for us all because she was never really convinced that she had Alzheimer's. We had little hope of talking to her of the “what if” and the “what then”.

What we had to work with was no living with family, no living alone, no support groups, and her often stated wish to move into a “retirement village” when she felt ready.

And so the visits began: independent living units, low-care accommodation, hostels. She was very positive about some of these places but would backpedal if we suggested a follow up visit or a trial stay. She enjoyed the outings and we kept a list of possibilities for later on.

My mother was still living with a partner during the first five or so years post-Alzheimer's. This was untenable in the longer run given his health and my mother's gradual but unrelenting memory loss. But neither of them would be hurried or forced, no matter how inevitable the future.

Finally the time arrived. He needed to go and a choice had to be made.

My mother agreed to try moving to a small unit in a village-style place five minutes from her former home and 10 minutes from where her partner was living. We had our doubts but she went willingly and that was a blessing.

She lasted just weeks. Her memory, understanding and orientation declined dramatically, as she tried and failed to negotiate her new way of life without live-in support. The village management recommended we try elsewhere, and quickly.

Next was a “low-care” home we had visited previously, close enough to my older sister and not too far from Mum's partner, to make regular visiting easy enough.

This was also short lived. My mother walked out the front door. While the care manager had been happy to accept her knowing she had moderate-to-middling-dementia, she was not so accommodating when Mother decided she needed a walk, and the street outside looked pretty good to her.

It also proved to be too big. Mum struggled to find her way from the dining room to her bedroom. Getting lost only increased her fear and frustration.

MY MOTHER died a little over five years ago of pancreatic cancer and with Alzheimer's disease. She was in her 90th year. Her cancer was advanced at diagnosis and speedy in its progress; from confirmed to cremated in about six weeks.

This was all in stark contrast to the progress of her unique experience of dementia, where the signs and symptoms emerged more than 10 years before her death.

These years were confounding and frustrating for us all because she was never really convinced that she had Alzheimer's. We had little hope of talking to her of the “what if” and the “what then”.

What we had to work with was no living with family, no living alone, no support groups, and her often stated wish to move into a “retirement village” when she felt ready.

And so the visits began: independent living units, low-care accommodation, hostels. She was very positive about some of these places but would backpedal if we suggested a follow up visit or a trial stay. She enjoyed the outings and we kept a list of possibilities for later on.

My mother was still living with a partner during the first five or so years post-Alzheimer's. This was untenable in the longer run given his health and my mother's gradual but unrelenting memory loss. But neither of them would be hurried or forced, no matter how inevitable the future.

Finally the time arrived. He needed to go and a choice had to be made.

My mother agreed to try moving to a small unit in a village-style place five minutes from her former home and 10 minutes from where her partner was living. We had our doubts but she went willingly and that was a blessing.

She lasted just weeks. Her memory, understanding and orientation declined dramatically, as she tried and failed to negotiate her new way of life without live-in support. The village management recommended we try elsewhere, and quickly.

Next was a “low-care” home we had visited previously, close enough to my older sister and not too far from Mum's partner, to make regular visiting easy enough.

This was also short lived. My mother walked out the front door. While the care manager had been happy to accept her knowing she had moderate-to-middling-dementia, she was not so accommodating when Mother decided she needed a walk, and the street outside looked pretty good to her.

It also proved to be too big. Mum struggled to find her way from the dining room to her bedroom. Getting lost only increased her fear and frustration.

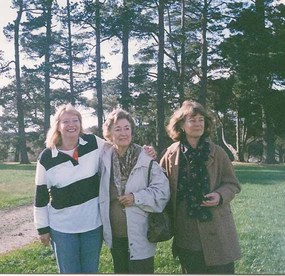

Maria Cawcutt with two of her daughters, Prue and Janet, 2001, a year after she was diagnosed

Maria Cawcutt with two of her daughters, Prue and Janet, 2001, a year after she was diagnosed with Alzheimer's.

We had a second look at a hostel very close to my sister. It was modest in size – just 28 bedrooms – and unpretentiously but comfortably fitted out and furnished. There was a garden, slightly unkempt in spots but with some lovely tall gum trees and big windows in the living spaces and some rooms.

My sister chose a room not too far from the dining room with a view of a stand of gum trees. We managed to negotiate for a care assistant to accompany Mum on a daily walk and for a keypad lock to be fitted to the front entrance. There was another resident with fairly severe dementia already living there but she was not a walker.

There were some unkind remarks overheard from the other residents when Mum couldn't find her allocated place at the dining table. But they accepted her in time. It was remarkable to me that she took to the place so well, joining in enthusiastically with the exercise sessions and winning the bingo! Bingo! My sisters and I found this both funny and touching.

We got to know the staff; the carers, the cleaners, the kitchen staff and laundry lady. One of my sisters volunteered as a recreation assistant, leading a group crossword puzzle session. We sat with Mum in the garden, walked the nearby streets and delivered her safely home. There were sad farewells at the end of our regular visits but over time her life was experienced in a fairly constant present. She forgot we had been almost before we left the building. There were days when she did not know us until we said our names several times over.

This was to be home until the last four months of her life, when she came to live with me. The hostel, which had a series of a care managers in its last 12 months of operating (a sure sign that something was amiss), suddenly announced it was closing down and all residents and staff were given notice.

This forced my hand. I could not bear the thought of moving my mother to the next level of care in a hurry. Finding a suitable dementia-specific unit would take time. And while that was our eventual aim, she would live with me until one could be found.

My sister chose a room not too far from the dining room with a view of a stand of gum trees. We managed to negotiate for a care assistant to accompany Mum on a daily walk and for a keypad lock to be fitted to the front entrance. There was another resident with fairly severe dementia already living there but she was not a walker.

There were some unkind remarks overheard from the other residents when Mum couldn't find her allocated place at the dining table. But they accepted her in time. It was remarkable to me that she took to the place so well, joining in enthusiastically with the exercise sessions and winning the bingo! Bingo! My sisters and I found this both funny and touching.

We got to know the staff; the carers, the cleaners, the kitchen staff and laundry lady. One of my sisters volunteered as a recreation assistant, leading a group crossword puzzle session. We sat with Mum in the garden, walked the nearby streets and delivered her safely home. There were sad farewells at the end of our regular visits but over time her life was experienced in a fairly constant present. She forgot we had been almost before we left the building. There were days when she did not know us until we said our names several times over.

This was to be home until the last four months of her life, when she came to live with me. The hostel, which had a series of a care managers in its last 12 months of operating (a sure sign that something was amiss), suddenly announced it was closing down and all residents and staff were given notice.

This forced my hand. I could not bear the thought of moving my mother to the next level of care in a hurry. Finding a suitable dementia-specific unit would take time. And while that was our eventual aim, she would live with me until one could be found.

Maria Cawcutt and the author, Wonthaggi, 2009

Maria Cawcutt and the author, Wonthaggi, 2009

What a blessing that hostel closure turned out to be. Three months into her stay she became terribly ill. Thankfully she had just one week in hospital. This was tough on her despite the good work of all involved.

There was no doubt in my mind that she should come home and that palliative care would see us to the end.

She did not know me as her daughter in these last weeks. I was a kindly presence in her gloaming world. This in turn allowed me to provide the intimate care she needed without embarrassment to her or me. Finally, it was the last reduction to the bed, the dosage and the breath. All that had gone before came down to that.

There was never a question about how my mother would live in her old, old age. It would be in a community of sorts; she hated the idea of living alone.

And it would be a compromise for her, and for all who cared about her.

I do not believe that to be in need of help is to be helpless. My mother showed me this.

COMMENTS

April 3, 2015

Thank you, Linda. Your story brings back memories of life with our mother aftershe was diagnosed with dementia. Maria was a fortunate lady.

Felicia Di Stefano, Glen Forbes

March 22, 2015

Thank you Linda, a story of care and love so beautifully told.

In what appears to be a week of reflection on aging and aged care

I doubt if I will read anything more moving.

Bob Middleton, Jeetho West

There was no doubt in my mind that she should come home and that palliative care would see us to the end.

She did not know me as her daughter in these last weeks. I was a kindly presence in her gloaming world. This in turn allowed me to provide the intimate care she needed without embarrassment to her or me. Finally, it was the last reduction to the bed, the dosage and the breath. All that had gone before came down to that.

There was never a question about how my mother would live in her old, old age. It would be in a community of sorts; she hated the idea of living alone.

And it would be a compromise for her, and for all who cared about her.

I do not believe that to be in need of help is to be helpless. My mother showed me this.

COMMENTS

April 3, 2015

Thank you, Linda. Your story brings back memories of life with our mother aftershe was diagnosed with dementia. Maria was a fortunate lady.

Felicia Di Stefano, Glen Forbes

March 22, 2015

Thank you Linda, a story of care and love so beautifully told.

In what appears to be a week of reflection on aging and aged care

I doubt if I will read anything more moving.

Bob Middleton, Jeetho West

Open letter to Russell Broadbent

|

November 15, 2014

Dear Mr Broadbent LAST Sunday I signed a petition, addressed to you, which called on the Australian government to take a more humane approach to the treatment of asylum seekers. |

Stormy Waters: a play about us and them will be performed at Foster Uniting Church, 36 Station Road, at 2.30pm on Sunday, November 23. Admission is free and all are welcome.

|

Parishioners and visitors were asked to put their name to the petition at the close of a short musical play, exploring the refugee issue, held at the Wonthaggi Anglican Church. Stormy Waters will be performed in several other churches within your electorate in coming weeks. The church was almost full and people applauded warmly.

It occurred to me that this was just the right place to hear a call for greater compassion for these displaced, traumatised and vulnerable people seeking refuge with us. Leaving the church, I wondered how I could show solidarity with this timely reminder of our obligations to those who are suffering and asking for our help.

Thankfully I decided to visit your website first to see if this was indeed an issue you had raised with your fellow parliamentarians. It was a great relief to read your speeches to Parliament of July 8 and May 29 this year, as well as a speech given on June 21, 2013. They were inspiring and decent; all that we look for in our elected leaders.

May I just briefly remind you of the words you chose when paying tribute to the inspiring Christian, John McIntyre, Bishop of Gippsland, who died in July this year? You spoke to Parliament of a man whose heart “lay with the alien and the outsider”, of a man “passionate about the needs of dispossessed people ... reaching out to alienated people and helping them find community”. You said he was a man of great compassion. And you note that three weeks before his death he made a speech calling on the government and community to offer compassion and justice to asylum seekers.

Last year you asked Parliament to reflect on new data about refugee movements across the globe. In this speech you acknowledge the genuine community concerns about accepting asylum seekers. “I understand that people fear these situations. I am concerned about that. We can address that. But let us try to work through this new paradigm together, this new world that we live in, which is not the same as the 1950s, in the best interests of this nation and its people.”

Your sentiments are wise, compassionate and pragmatic.

Will you also use such compelling language and considered argument when you present the petition I and others signed to your fellows in Parliament?

A great challenge comes with it but you have shown in word and deed that you are more than equal to it.

I take heart not just from your quoted words about the late Bishop of Gippsland but also from your address to Parliament in May, regarding a meeting with members of the Corner Inlet Social Justice Group.

“It was a pressure time. It was an exhausting time, but it was a pleasurable time, to know that there are people in our community who actually take a direct interest in what is going on and are prepared to come out, sit down and discuss the issues with their local member.

“Consider carefully how you make your decisions.”

Thank you for taking the time to consider this letter.

Yours sincerely

Linda Gordon, Wonthaggi

COMMENTS

November 16, 2014

Congratulations to Linda Gordon on her fine letter to Russell Broadbent, a member of the Liberal Government who has also earned my respect for his stand on asylum seekers. Congratulations too for the article Political prisoners on how hard it must be for idealists to stick to their ideals in politics. Well, Russell Broadbent is one who is trying to!

Best wishes to you and Bass Coast Post. You are doing a magnificent job presenting thoughts, opinions, ideas and news that might otherwise not be aired.

Meryl Tobin

It occurred to me that this was just the right place to hear a call for greater compassion for these displaced, traumatised and vulnerable people seeking refuge with us. Leaving the church, I wondered how I could show solidarity with this timely reminder of our obligations to those who are suffering and asking for our help.

Thankfully I decided to visit your website first to see if this was indeed an issue you had raised with your fellow parliamentarians. It was a great relief to read your speeches to Parliament of July 8 and May 29 this year, as well as a speech given on June 21, 2013. They were inspiring and decent; all that we look for in our elected leaders.

May I just briefly remind you of the words you chose when paying tribute to the inspiring Christian, John McIntyre, Bishop of Gippsland, who died in July this year? You spoke to Parliament of a man whose heart “lay with the alien and the outsider”, of a man “passionate about the needs of dispossessed people ... reaching out to alienated people and helping them find community”. You said he was a man of great compassion. And you note that three weeks before his death he made a speech calling on the government and community to offer compassion and justice to asylum seekers.

Last year you asked Parliament to reflect on new data about refugee movements across the globe. In this speech you acknowledge the genuine community concerns about accepting asylum seekers. “I understand that people fear these situations. I am concerned about that. We can address that. But let us try to work through this new paradigm together, this new world that we live in, which is not the same as the 1950s, in the best interests of this nation and its people.”

Your sentiments are wise, compassionate and pragmatic.

Will you also use such compelling language and considered argument when you present the petition I and others signed to your fellows in Parliament?

A great challenge comes with it but you have shown in word and deed that you are more than equal to it.

I take heart not just from your quoted words about the late Bishop of Gippsland but also from your address to Parliament in May, regarding a meeting with members of the Corner Inlet Social Justice Group.

“It was a pressure time. It was an exhausting time, but it was a pleasurable time, to know that there are people in our community who actually take a direct interest in what is going on and are prepared to come out, sit down and discuss the issues with their local member.

“Consider carefully how you make your decisions.”

Thank you for taking the time to consider this letter.

Yours sincerely

Linda Gordon, Wonthaggi

COMMENTS

November 16, 2014

Congratulations to Linda Gordon on her fine letter to Russell Broadbent, a member of the Liberal Government who has also earned my respect for his stand on asylum seekers. Congratulations too for the article Political prisoners on how hard it must be for idealists to stick to their ideals in politics. Well, Russell Broadbent is one who is trying to!

Best wishes to you and Bass Coast Post. You are doing a magnificent job presenting thoughts, opinions, ideas and news that might otherwise not be aired.

Meryl Tobin

The streets of my town

|

By Linda Gordon

October 19, 2013 A RECENT report on Wonthaggi’s future development to accommodate Melbourne’s overflow and “protect the coastal towns” of Bass Coast (Wonthaggi poised for growth spurt, October 12, 2013) has made me uneasy. Maybe this country town needs protection too? I wonder if you’ve had a chance to walk, cycle or drive through Wonthaggi’s recently finished Heartlands housing estate. The foreground is all neat kerbing, bitumen curves, light poles and small trees in grow bags. But beyond this tidy, if slightly cramped, aspect is a huge slab of concrete backside belonging to the retail giants Coles, Liquorland and Target. All sightlines lead to the big, bold brands. Plenty of people will want to live close to the shops but will they want to live with the shops? Still, there is open space on two sides, a walking path and a place to sit. And most of the time, we don’t pay much attention to this advertising visual pollution because it is everywhere in urban and suburban places. There is a lingering uneasiness, though. We are going to see a lot more housing developments like Heartlands in Wonthaggi. Not so close to the Plaza, perhaps, but with similar narrow roads, which don’t always cope with two-and- three- car households, plus visitors. Compare the estate look to the established streets of the town, with their predominantly green and interesting streetscapes, that tell the story of Wonthaggi’s settlement. If we are to have more planned developments, and we are, the informal beauty of streets in this country town becomes a precious resource. They are rich in nature, social history and diversity; the car does not dominate. Their scale is human not commercial. |

Do you have a favourite street in your town? Send in a photo and a description of what you like about it and help us record the everyday, informal beauty of the streets in our coastal and country towns.

|

One of my favourites is Broome Crescent with its gentle curves and dips, mature trees, minimal hard landscaping and old timber houses. It chimes exactly with its era and setting in a medium-sized country town established in the early decades of last century.