By Catherine Watson

THE death of renowned gallery director James Mollison last month has revived memories of his most controversial purchase for the National Art Gallery of Australia: Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles.

In 1973, on Mollison’s advice, the gallery paid $1.3 million for the modernist work, then a record price for any work by an American artist or for an Australian gallery. It required sign-off by then prime minister Gough Whitlam, and critics decried it as typical of the excess and waste of the Labor government.

Few locals are aware that Mollison was a local boy, born in Wonthaggi in 1931.

THE death of renowned gallery director James Mollison last month has revived memories of his most controversial purchase for the National Art Gallery of Australia: Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles.

In 1973, on Mollison’s advice, the gallery paid $1.3 million for the modernist work, then a record price for any work by an American artist or for an Australian gallery. It required sign-off by then prime minister Gough Whitlam, and critics decried it as typical of the excess and waste of the Labor government.

Few locals are aware that Mollison was a local boy, born in Wonthaggi in 1931.

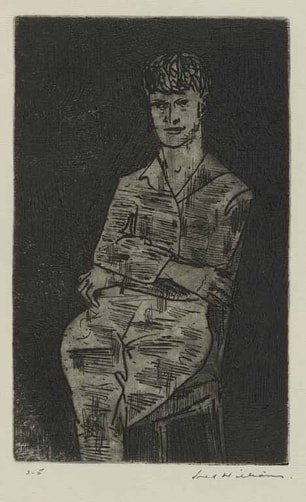

James Mollison, etching, Fred Williams 1964-65, NGA,

James Mollison, etching, Fred Williams 1964-65, NGA, Local historian Nola Thorpe has unearthed a cutting from the Wonthaggi Sentinel of October 3 1968, as Mollison heads to Canberra for his new role as founding director of the NGA, scheduled to be completed in 1972.

The short Sentinel article states: “He is a son of Mr James Mollison, of Sorrento, and grandson of Mr James Mollison, Snr., of Merrin Crescent, Wonthaggi.

“His work before the opening will include cataloguing a national collection of paintings, advise the Commonwealth Arts Advisory Board on additional collections, and work in conjunction with the architects in planning the national gallery.”

Realising the gallery had missed the boat on the old European masters, Mollison turned his attention to modern American works, Australian art (particularly Aboriginal works) and works from the Pacific and south-east Asia.

The Blue Poles purchase attracted howls of derision from many quarters. “$1.3m for dribs and drabs”, read one headline. “Barefoot drunks painted our $1 million masterpiece”, read another.

Liberal Senator Condor Laucke suggested the Australian advisers (Mollison) had been “taken for a ride by some sharpies in New York".

There were "major old masters" available for the price paid for the painting, he said.

"There are quite important Australian collections such as that of Sir James McGregor which would be typically desirable for our gallery" he said.

The short Sentinel article states: “He is a son of Mr James Mollison, of Sorrento, and grandson of Mr James Mollison, Snr., of Merrin Crescent, Wonthaggi.

“His work before the opening will include cataloguing a national collection of paintings, advise the Commonwealth Arts Advisory Board on additional collections, and work in conjunction with the architects in planning the national gallery.”

Realising the gallery had missed the boat on the old European masters, Mollison turned his attention to modern American works, Australian art (particularly Aboriginal works) and works from the Pacific and south-east Asia.

The Blue Poles purchase attracted howls of derision from many quarters. “$1.3m for dribs and drabs”, read one headline. “Barefoot drunks painted our $1 million masterpiece”, read another.

Liberal Senator Condor Laucke suggested the Australian advisers (Mollison) had been “taken for a ride by some sharpies in New York".

There were "major old masters" available for the price paid for the painting, he said.

"There are quite important Australian collections such as that of Sir James McGregor which would be typically desirable for our gallery" he said.

Blue Poles continues to divide and intrigue people.

"Never had such a picture moved and disturbed the Australian public," art historian and gallery director Patrick McCaughey told a Blue Poles symposium in Sydney in 2012.

Mollison not only survived the storm but went on to be vindicated with Blue Poles becoming a crowd favourite and its value rising exponentially. Today it’s estimated to be worth up to $450 million – except that it’s not for sale.

Little is known about Mollison’s early life in Wonthaggi. One wonders how the young man – cultured, gay – coped in the working class world of 1940s Wonthaggi.

Grazia Gunn, who is writing a history of Mollison’s years at the NGA, writes that Mollison developed a passion for art at a young age. Despite the absence of mothers and grandmothers from the Sentinel article, his mother was certainly an important figure in his life.

“He spent weekends with his mother at the Melbourne Public Library, now the State Library of Victoria, when the building also housed the museum, the National Gallery of Victoria and the art school.”

He would also visit the US information to read Life and other magazines and books that featured American artists and culture.

“At the age of 16 he asked NGV gallery director Daryl Lindsay for a job. Lindsay casually responded: ‘Yes, but later.’ Mollison arrived at his office the next day, ready for work, several decades before he would eventually return to the gallery as education officer and then director.

"Never had such a picture moved and disturbed the Australian public," art historian and gallery director Patrick McCaughey told a Blue Poles symposium in Sydney in 2012.

Mollison not only survived the storm but went on to be vindicated with Blue Poles becoming a crowd favourite and its value rising exponentially. Today it’s estimated to be worth up to $450 million – except that it’s not for sale.

Little is known about Mollison’s early life in Wonthaggi. One wonders how the young man – cultured, gay – coped in the working class world of 1940s Wonthaggi.

Grazia Gunn, who is writing a history of Mollison’s years at the NGA, writes that Mollison developed a passion for art at a young age. Despite the absence of mothers and grandmothers from the Sentinel article, his mother was certainly an important figure in his life.

“He spent weekends with his mother at the Melbourne Public Library, now the State Library of Victoria, when the building also housed the museum, the National Gallery of Victoria and the art school.”

He would also visit the US information to read Life and other magazines and books that featured American artists and culture.

“At the age of 16 he asked NGV gallery director Daryl Lindsay for a job. Lindsay casually responded: ‘Yes, but later.’ Mollison arrived at his office the next day, ready for work, several decades before he would eventually return to the gallery as education officer and then director.