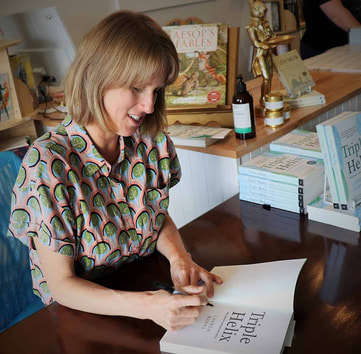

Photo: Geoff Ellis

Photo: Geoff Ellis AFTER book launches of Triple Helix: my donor-conceived story in Sydney and Melbourne, Inverloch writer Lauren was among friends for her local launch, at Hare and Tortoise Books in Korumburra this week. She was in conversation with Catherine Watson, editor of the Bass Coast Post.

Catherine: After many years of searching, you finally found your donor father. You describe coming down to Bass Coast to meet Ben for the first time. Every reader can feel the tension. And when you meet him you notice parts of yourself in Ben and his two children. Not just physical characteristics but interests and even gestures.

Lauren: It was really bizarre. Almost like a blind date. It was a very surreal experience being in a room surrounded by people who look like you. It feels familiar but they’re also strangers you’ve never met before. In a way that first contact was like a jigsaw piece falling into place. The first letter and the first phone call and the first meeting. It was quite a relief to see we did have a lot of similarities. His siblings reflected my dual love of words and writing but also equations and engineering. Hs brother is a maths teacher, another brother is an English language academic, one was a journalist. I could definitely recognise those elements. We all love nature. We all drove Subaru Foresters, oddly enough. (Laughter) I don’t know if that’s genetic but it lined up. We all dropped crumbs down our shirts!

Catherine: You had been mysteriously attracted to the German language.

Lauren: It was really bizarre. Almost like a blind date. It was a very surreal experience being in a room surrounded by people who look like you. It feels familiar but they’re also strangers you’ve never met before. In a way that first contact was like a jigsaw piece falling into place. The first letter and the first phone call and the first meeting. It was quite a relief to see we did have a lot of similarities. His siblings reflected my dual love of words and writing but also equations and engineering. Hs brother is a maths teacher, another brother is an English language academic, one was a journalist. I could definitely recognise those elements. We all love nature. We all drove Subaru Foresters, oddly enough. (Laughter) I don’t know if that’s genetic but it lined up. We all dropped crumbs down our shirts!

Catherine: You had been mysteriously attracted to the German language.

Lauren: Yes, I was always drawn to German, which is strange. Most people think it’s an ugly language, not as beautiful as French or Spanish. I found out that Ben’s mother Dymphna was very talented at languages. She won the Gold Medal for German at Melbourne University and she translated early German explorers’ journals into English. She translated Baron von Hügel’s journal.

Catherine: When you found out about your donor father, your mother realised his father was Manning Clark, famous Australian author and historian. Had you heard of him?

Lauren: He’s not quite so famous in my generation as my mother’s but I had heard of him. When I read in Ben’s letter that his father was Manning, my mother said “Oh my gosh, his father’s Manning Clark!” She went to the bookshelf and pulled out his autobiography. She flipped through and there’s a photo of the family. So a photo of my biological father was in the house all the years I was searching for him!

I loved the way Ben described his dad as “an annoyer of conservatives”. That resonated with me as well.

Catherine: Anonymous donor insemination was carried out in Victoria hospitals. No one needed to know … people were told to go home and forget it ever happened.

Lauren: I call it a psychological treatment as much as a physical treatment. I was conceived in the 1980s. Secrecy was seen as essential to keep the sanctity of the nuclear family intact. Sometimes they actually mixed sperm from the husband with the donor, sometimes they told them to go home and make love. The psychological salve was to bury it. That’s why it’s difficult for parents to deal with it. The husband might not have dealt with the grief of infertility.

So it wasn’t talked about. It was quite taboo. Really it was incredibly damaging for people like me when we grew up. The secret leaches out inevitably. We saw that with similar cohorts like adoptees or people in care or child migrants or the Stolen Generations. To erase this information is like a wound.

Catherine: When you found out about your donor father, your mother realised his father was Manning Clark, famous Australian author and historian. Had you heard of him?

Lauren: He’s not quite so famous in my generation as my mother’s but I had heard of him. When I read in Ben’s letter that his father was Manning, my mother said “Oh my gosh, his father’s Manning Clark!” She went to the bookshelf and pulled out his autobiography. She flipped through and there’s a photo of the family. So a photo of my biological father was in the house all the years I was searching for him!

I loved the way Ben described his dad as “an annoyer of conservatives”. That resonated with me as well.

Catherine: Anonymous donor insemination was carried out in Victoria hospitals. No one needed to know … people were told to go home and forget it ever happened.

Lauren: I call it a psychological treatment as much as a physical treatment. I was conceived in the 1980s. Secrecy was seen as essential to keep the sanctity of the nuclear family intact. Sometimes they actually mixed sperm from the husband with the donor, sometimes they told them to go home and make love. The psychological salve was to bury it. That’s why it’s difficult for parents to deal with it. The husband might not have dealt with the grief of infertility.

So it wasn’t talked about. It was quite taboo. Really it was incredibly damaging for people like me when we grew up. The secret leaches out inevitably. We saw that with similar cohorts like adoptees or people in care or child migrants or the Stolen Generations. To erase this information is like a wound.

Triple Helixby Lauren Burns is on sale at Hare and Tortoise Books in Korumburra and all good bookshops.

Triple Helixby Lauren Burns is on sale at Hare and Tortoise Books in Korumburra and all good bookshops. Catherine: Your mother was quite remarkable for telling you. She also had had her own family secrets …

Lauren: She’s an identical twin. That genetic cloning was something she’s always struggled with, simply because of the way she was brought up. The twins were always together and it was difficult for them to form their individual identity. There were always those attacks on Manning Clark for supposed Communist links but my mother’s father actually was a Communist. When they matched the donor they did a good job! He was Irish and had fled his family. He always portrayed himself as working class man but we found out later he came from a middle class background back in Ireland but he’d severed ties with that and passionately believed the Soviet model offered a better world.

Then we found out recently that before he had four other marriages before my grandmother! I think family secrets are actually very common!

Catherine: DNA testing means the secrets can’t be kept any more.

Lauren: The technology has been a game changer. You can buy a kit from Ancestry.com for $100 and upload to a database. My own search took me many years but these days it can proceed at lightning pace. There was this hierarchy of doctors and clinics and lawmakers and legislators and we always felt disempowered. There were always gatekeepers to this information and donor-conceived people never had access to it but now through the DNA in our own cells people are taking back power and searching for information.

Lauren: She’s an identical twin. That genetic cloning was something she’s always struggled with, simply because of the way she was brought up. The twins were always together and it was difficult for them to form their individual identity. There were always those attacks on Manning Clark for supposed Communist links but my mother’s father actually was a Communist. When they matched the donor they did a good job! He was Irish and had fled his family. He always portrayed himself as working class man but we found out later he came from a middle class background back in Ireland but he’d severed ties with that and passionately believed the Soviet model offered a better world.

Then we found out recently that before he had four other marriages before my grandmother! I think family secrets are actually very common!

Catherine: DNA testing means the secrets can’t be kept any more.

Lauren: The technology has been a game changer. You can buy a kit from Ancestry.com for $100 and upload to a database. My own search took me many years but these days it can proceed at lightning pace. There was this hierarchy of doctors and clinics and lawmakers and legislators and we always felt disempowered. There were always gatekeepers to this information and donor-conceived people never had access to it but now through the DNA in our own cells people are taking back power and searching for information.

Lauren Burns was in conversation with Catherine Watson.

Lauren Burns was in conversation with Catherine Watson. Catherine: The assisted donor system was flawed but at least it was part of the public health system. What’s the situation now?

Lauren: It’s become much more globalised. There’s a lot of pressure to allow for the importation of eggs and sperm. I find the whole idea of the industry really gross. A human being is not a commodity. There’s a clinic based in Victoria which markets itself as low-cost. It imports its eggs from the UK, which sounds okay, but those eggs from the UK actually come mostly from women in Ukraine. Ukraine now is also the global capital for low-cost surrogacy as well, basically because of the dynamic of poverty and whiteness. A healthy human egg from a young white woman is worth more than gold.

There is a lot of shady exploitation. Women may feel they have no choice but to sell their reproductive capabilities. You see shades of it in Russian or Ukraine where women say they feel as though they were treated like a milking cow.

Altruistic systems using local and known donors can be much better. In the donor-coneived community, we believe the way to go about it is forming relationships.

Lauren: It’s become much more globalised. There’s a lot of pressure to allow for the importation of eggs and sperm. I find the whole idea of the industry really gross. A human being is not a commodity. There’s a clinic based in Victoria which markets itself as low-cost. It imports its eggs from the UK, which sounds okay, but those eggs from the UK actually come mostly from women in Ukraine. Ukraine now is also the global capital for low-cost surrogacy as well, basically because of the dynamic of poverty and whiteness. A healthy human egg from a young white woman is worth more than gold.

There is a lot of shady exploitation. Women may feel they have no choice but to sell their reproductive capabilities. You see shades of it in Russian or Ukraine where women say they feel as though they were treated like a milking cow.

Altruistic systems using local and known donors can be much better. In the donor-coneived community, we believe the way to go about it is forming relationships.