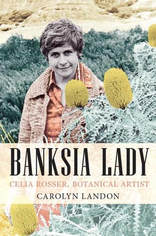

Carolyn Landon’s new biography of Celia Rosser matches the skill of the author with that of the artist, writes Kay Patterson.

From left: Kay Patterson, Celia Rosser and Carolyn Landon at the launch of Banksia Lady: Photo: Alex Smart,

From left: Kay Patterson, Celia Rosser and Carolyn Landon at the launch of Banksia Lady: Photo: Alex Smart, CAROLYN Landon has captured Celia Rosser to a tee – her growth as a person, the ups and downs she has confronted, her development as a botanical artist, her love of storytelling and her sense of humour and infectious laugh. Those of us who know Celia see her in the pages of this biography and those who don’t, but love her work, will grow to know the person and to appreciate even more her genius as one of the great botanical artists and the only one to have painted a whole genus.

She has deftly woven her into a broad tapestry of the discovery and history of Australia after British settlement, the history and development of botanical art, the major players in this area and the social changes in Australia.

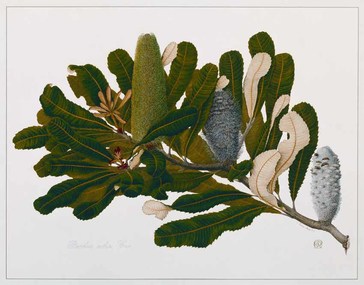

She enlightens us about the challenges Celia had in capturing the beauty of mosses and banksias while ensuring the illustration of these is scientifically accurate, the attention to detail applied by Celia in choosing her specimens and ensuring the accuracy of her representations, her use of field sketches, numerous tracings and colour roughs.

She explains how Celia uses the same attention to detail to select her tools of trade, the paints and colours – I know there is at least one colour she uses, the name of which she holds close to her chest, I could only disclose it at the risk of pain of death. The paper she chooses, the light source by which she paints, are also carefully considered.

As I was reading some of the stories Carolyn related, especially about one or two field trips, I could almost hear Celia’s characteristic chuckle – sometimes a mischievous chuckle – which more often than not burst into a full blown laugh.

One, retold in the book was about Celia’s first field trip to see banksias in their natural setting when the party pitched their tents in the middle of the night. Early next morning, when the road construction caterpillar and tip trucks came rumbling along dangerously close to them, they realised they were camped in the middle of a road under construction.

The story of the banksias has involved a large number of people – academics, chancellors and vice-chancellors, botanists, biologists, bryologists, psychologists, photographers, anatomists, most from Monash University.

I was working on my PhD in the same building as Celia and got to know her through friends in the botany department. I was conscious that there was no real acknowledgment when Celia finished a banksia. Some of these would have taken well over a year from collection to completion, stopping and starting as she waited for another season. The work was lonely and demanding and the precision required meant endless hours leaning over her work, often using an illuminated magnifying glass, wreaking havoc on Celia’s back and eyes.

I had seen most of the banksias as they were painted, pored over the books and folios but, seeing them all at the National Library in Canberra brought a tear to my eye and a lump to my throat. It highlighted the magnitude of this magnificent and unique opus. Celia’s artistry and brilliance were on full display.

One way a person could stir Celia up was to say her work looked like a photograph or ask why she didn’t just photograph the banksias. Read the book and you will know why that would send her into a tailspin.

Celia’s mood could often be influenced by the banksia she was painting – dark and foreboding Robur, the nightmarish tangle of Dryandroides leaves, or the “mad blonde” Lullfitzii which nearly drove her mad – each banksia produced a different response – they are all so different.

Carolyn talks about the changes between the six banksia paintings Celia undertook for the Victorian Herbarium, funded by the Maud Gibson Trust, and the Monash banksias. She explains in Chapter 13 Celia’s frustration: “She was feeling the drawings were flat, that no matter what she did she could not find the perspective to give it depth and volume”.

She then explains Celia’s epiphany: “I looked away from the page in disgust and there was a spare fruiting cone lying on the desk. I was looking at it from the top – like a cross-section – and I could see the old dried up florets coming out of it like a spiral. I could see the spiral one way and the spiral the other way were at two different angles. I rushed out the door, and nearly knocked Professor Canny over. I held the cone up to him and said ‘Look! Look at this!’ and he said, ‘Oh, yes, the spiral. The Fibonacci Spiral. We didn’t think to tell you’. He then gave her some literature to read but she says she really worked it out for herself, ‘When you get the two spirals right and the rows turn in properly, then you have the perspective’.” Carolyn says, “Never again would her paintings look flat.”.

Celia was determined to ensure her paintings had perspective and they do. Carolyn has done the same with her literary skills and artistry – in her own way she has painted Celia in her various stages as a person and an artist. As you read through the book you see Celia blossom and grow into a superb and world renowned botanical artist. It’s a wonderful biography diligently researched, detailed, sensitive and, in its own way, it has depth and perspective.

In 1992 when Volume II was to be presented to the Queen in Canberra, Celia told me how nervous she was. I said to her, “Celia, there will be hundreds of people in the Great Hall – the Prime Minister, former prime ministers, ambassadors, high commissioners, High Court judges – all hoping to be remembered in posterity. But the only two who will be remembered in a hundred years are Queen Elizabeth as the longest reigning British monarch and Celia Rosser.”

Kay Patterson was a Liberal Party Senator for Victoria from 1987 to 2008 and a Vice Chancellor's Professorial Fellow at Monash University. This is the edited text of the speech she gave to launch Banksia Lady at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Cranbourne, last Sunday.

She has deftly woven her into a broad tapestry of the discovery and history of Australia after British settlement, the history and development of botanical art, the major players in this area and the social changes in Australia.

She enlightens us about the challenges Celia had in capturing the beauty of mosses and banksias while ensuring the illustration of these is scientifically accurate, the attention to detail applied by Celia in choosing her specimens and ensuring the accuracy of her representations, her use of field sketches, numerous tracings and colour roughs.

She explains how Celia uses the same attention to detail to select her tools of trade, the paints and colours – I know there is at least one colour she uses, the name of which she holds close to her chest, I could only disclose it at the risk of pain of death. The paper she chooses, the light source by which she paints, are also carefully considered.

As I was reading some of the stories Carolyn related, especially about one or two field trips, I could almost hear Celia’s characteristic chuckle – sometimes a mischievous chuckle – which more often than not burst into a full blown laugh.

One, retold in the book was about Celia’s first field trip to see banksias in their natural setting when the party pitched their tents in the middle of the night. Early next morning, when the road construction caterpillar and tip trucks came rumbling along dangerously close to them, they realised they were camped in the middle of a road under construction.

The story of the banksias has involved a large number of people – academics, chancellors and vice-chancellors, botanists, biologists, bryologists, psychologists, photographers, anatomists, most from Monash University.

I was working on my PhD in the same building as Celia and got to know her through friends in the botany department. I was conscious that there was no real acknowledgment when Celia finished a banksia. Some of these would have taken well over a year from collection to completion, stopping and starting as she waited for another season. The work was lonely and demanding and the precision required meant endless hours leaning over her work, often using an illuminated magnifying glass, wreaking havoc on Celia’s back and eyes.

I had seen most of the banksias as they were painted, pored over the books and folios but, seeing them all at the National Library in Canberra brought a tear to my eye and a lump to my throat. It highlighted the magnitude of this magnificent and unique opus. Celia’s artistry and brilliance were on full display.

One way a person could stir Celia up was to say her work looked like a photograph or ask why she didn’t just photograph the banksias. Read the book and you will know why that would send her into a tailspin.

Celia’s mood could often be influenced by the banksia she was painting – dark and foreboding Robur, the nightmarish tangle of Dryandroides leaves, or the “mad blonde” Lullfitzii which nearly drove her mad – each banksia produced a different response – they are all so different.

Carolyn talks about the changes between the six banksia paintings Celia undertook for the Victorian Herbarium, funded by the Maud Gibson Trust, and the Monash banksias. She explains in Chapter 13 Celia’s frustration: “She was feeling the drawings were flat, that no matter what she did she could not find the perspective to give it depth and volume”.

She then explains Celia’s epiphany: “I looked away from the page in disgust and there was a spare fruiting cone lying on the desk. I was looking at it from the top – like a cross-section – and I could see the old dried up florets coming out of it like a spiral. I could see the spiral one way and the spiral the other way were at two different angles. I rushed out the door, and nearly knocked Professor Canny over. I held the cone up to him and said ‘Look! Look at this!’ and he said, ‘Oh, yes, the spiral. The Fibonacci Spiral. We didn’t think to tell you’. He then gave her some literature to read but she says she really worked it out for herself, ‘When you get the two spirals right and the rows turn in properly, then you have the perspective’.” Carolyn says, “Never again would her paintings look flat.”.

Celia was determined to ensure her paintings had perspective and they do. Carolyn has done the same with her literary skills and artistry – in her own way she has painted Celia in her various stages as a person and an artist. As you read through the book you see Celia blossom and grow into a superb and world renowned botanical artist. It’s a wonderful biography diligently researched, detailed, sensitive and, in its own way, it has depth and perspective.

In 1992 when Volume II was to be presented to the Queen in Canberra, Celia told me how nervous she was. I said to her, “Celia, there will be hundreds of people in the Great Hall – the Prime Minister, former prime ministers, ambassadors, high commissioners, High Court judges – all hoping to be remembered in posterity. But the only two who will be remembered in a hundred years are Queen Elizabeth as the longest reigning British monarch and Celia Rosser.”

Kay Patterson was a Liberal Party Senator for Victoria from 1987 to 2008 and a Vice Chancellor's Professorial Fellow at Monash University. This is the edited text of the speech she gave to launch Banksia Lady at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Cranbourne, last Sunday.

Q&A with Carolyn LandonThe Post asked author Carolyn Landon about writing Banksia Lady.

Post: You’ve written four biographies about four very different people. What do you look for in a subject?

CL: Daryl Tonkin (Jacksons Track), Bette Boyanton (Cups with No Handles) and Eileen Harrison (Black Swan) all represented moments in our history: Daryl’s life was about Victorian Aboriginal life from the 30s through the 50s when the Protection Board was derelict and Aboriginal people were left pretty much to their own devices, although they had no rights and, finally, the disruption of that life with the formation of the Aboriginal Welfare Board; Bette’s life represented the changes in women’s experiences throughout the 20th century, most tellingly change from the Great Depression to Second Wave Feminism; Kurnai artist, Eileen Harrison, grew up at Lake Tyers and suffered the terrible consequences of Assimilation Polices imposed upon her people.

On the other hand, the life of Celia Rosser is about Celia Rosser, world famous botanical artist. She is unique and represents no social movement in our history. Nevertheless, it was clear from the start that her life would send the reader on a journey that covers three centuries of discovery, science, art, the establishment of great scientific and cultural institutions… Her achievements seem to open up the world. I couldn’t turn away from writing her life, although it was unlike any life I had written.

Post: What made you decide Celia Rosser was “the one” for your next book?

CL: Paul and Wendy Satchell, who had had an exhibition of their art work at the Celia Rosser Gallery in Fish Creek, encouraged me to go see Celia and take her seriously. When Celia showed me the 18th Century style florilegium that was the culmination of her 25 years of painting the entire genus of Banksias, I was hooked. It is one of the most beautiful things I have ever seen; one of the great books of the 20th Century.

Post: How much did you know about botanical art when you took on the project?

CL: Nothing. I didn’t even understand that it was art. I thought is was science, pure and simple. It’s a terrible admission. Celia and many others put me straight.

Post: What do you enjoy most: the research or the writing?

CL: I need a “story” first of all to make research pleasurable. If I start by going to the archive without an idea of the narrative line I want to follow, the research is tedious, which means at the beginning of a project while I am still nutting out the core of the story, the research is difficult and confusing. Once I know where I am going, I enjoy both the writing and the research.

Post: There’s an immense amount of research behind each of your subjects. How hard is it to stop that research from overwhelming the story?

CL: Once I know the line I want to take, the research does not overwhelm the story.

Post: At the book launch, you mentioned that of all the books you’d written this was the one that took you most deeply into Australia. What did you mean?

CL: Doing a book about botany and botanical art has made me look around. I can now see my physical world with clearer eyes, from the shape of a leaf to the depth of a forest. Working with the Kurnai (Jackson’s Track) I learned that the Aboriginal soul lives in the rocks upon which this continent sits and that the ancestors are always present, which is why we need to acknowledge them for they are listening. With the Banksias, a plant that is 10 millions years old, I learned about the movement of continents. The story of the ‘discovery’ of banksias opened my imagination up to the migration of men (generic) to a ‘lost’ continent, to the discovery of what had always been here and a flowering of understanding about the world.

Post: What’s your next project?

CL: I am working on a book about Pauline Toner, a member of the Cain Labor government, the first woman in Victoria to be given a ministry and to sit on the Front Bench.

Carolyn Landon’s historical essays appear in the Bass Coast Post.

Post: You’ve written four biographies about four very different people. What do you look for in a subject?

CL: Daryl Tonkin (Jacksons Track), Bette Boyanton (Cups with No Handles) and Eileen Harrison (Black Swan) all represented moments in our history: Daryl’s life was about Victorian Aboriginal life from the 30s through the 50s when the Protection Board was derelict and Aboriginal people were left pretty much to their own devices, although they had no rights and, finally, the disruption of that life with the formation of the Aboriginal Welfare Board; Bette’s life represented the changes in women’s experiences throughout the 20th century, most tellingly change from the Great Depression to Second Wave Feminism; Kurnai artist, Eileen Harrison, grew up at Lake Tyers and suffered the terrible consequences of Assimilation Polices imposed upon her people.

On the other hand, the life of Celia Rosser is about Celia Rosser, world famous botanical artist. She is unique and represents no social movement in our history. Nevertheless, it was clear from the start that her life would send the reader on a journey that covers three centuries of discovery, science, art, the establishment of great scientific and cultural institutions… Her achievements seem to open up the world. I couldn’t turn away from writing her life, although it was unlike any life I had written.

Post: What made you decide Celia Rosser was “the one” for your next book?

CL: Paul and Wendy Satchell, who had had an exhibition of their art work at the Celia Rosser Gallery in Fish Creek, encouraged me to go see Celia and take her seriously. When Celia showed me the 18th Century style florilegium that was the culmination of her 25 years of painting the entire genus of Banksias, I was hooked. It is one of the most beautiful things I have ever seen; one of the great books of the 20th Century.

Post: How much did you know about botanical art when you took on the project?

CL: Nothing. I didn’t even understand that it was art. I thought is was science, pure and simple. It’s a terrible admission. Celia and many others put me straight.

Post: What do you enjoy most: the research or the writing?

CL: I need a “story” first of all to make research pleasurable. If I start by going to the archive without an idea of the narrative line I want to follow, the research is tedious, which means at the beginning of a project while I am still nutting out the core of the story, the research is difficult and confusing. Once I know where I am going, I enjoy both the writing and the research.

Post: There’s an immense amount of research behind each of your subjects. How hard is it to stop that research from overwhelming the story?

CL: Once I know the line I want to take, the research does not overwhelm the story.

Post: At the book launch, you mentioned that of all the books you’d written this was the one that took you most deeply into Australia. What did you mean?

CL: Doing a book about botany and botanical art has made me look around. I can now see my physical world with clearer eyes, from the shape of a leaf to the depth of a forest. Working with the Kurnai (Jackson’s Track) I learned that the Aboriginal soul lives in the rocks upon which this continent sits and that the ancestors are always present, which is why we need to acknowledge them for they are listening. With the Banksias, a plant that is 10 millions years old, I learned about the movement of continents. The story of the ‘discovery’ of banksias opened my imagination up to the migration of men (generic) to a ‘lost’ continent, to the discovery of what had always been here and a flowering of understanding about the world.

Post: What’s your next project?

CL: I am working on a book about Pauline Toner, a member of the Cain Labor government, the first woman in Victoria to be given a ministry and to sit on the Front Bench.

Carolyn Landon’s historical essays appear in the Bass Coast Post.