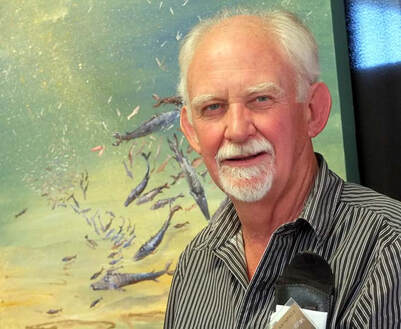

Ray Dahlstrom with A Legacy for the Ocean: “I don’t particularly like it. That’s not the point.”

Ray Dahlstrom with A Legacy for the Ocean: “I don’t particularly like it. That’s not the point.” By Catherine Watson

JELLYFISH and chips ... Ray Dahlstrom’s dire prediction of a future when the oceans are acid has been good to him, he admits. It’s been turned into T-shirts, fridge magnets, mugs.

The original image was from a painting called Acid Ocean. It depicts a future where there are no more fish in the oceans, just jellyfish.

The themes of Dahlstrom’s new exhibition, Legacy for the Ocean, are catastrophic but the paintings are glorious explosions of colour made three-dimensional with epoxy resin, sand and found materials.

JELLYFISH and chips ... Ray Dahlstrom’s dire prediction of a future when the oceans are acid has been good to him, he admits. It’s been turned into T-shirts, fridge magnets, mugs.

The original image was from a painting called Acid Ocean. It depicts a future where there are no more fish in the oceans, just jellyfish.

The themes of Dahlstrom’s new exhibition, Legacy for the Ocean, are catastrophic but the paintings are glorious explosions of colour made three-dimensional with epoxy resin, sand and found materials.

| Take A Legacy for the Ocean, a painting of a fish and jellyfish in netting after which the exhibition is named. “People love it or they hate it.” He shrugs. “I don’t particularly like it. That’s not the point. The point is to tell a story.” The images of the skeletal fish and the jellyfish came to him when he attended a talk at Kilcunda a couple of years ago and watched a science teacher use the litmus paper test to explain what happened to oceans when they absorbed too much carbon dioxide. Climate change was already at the forefront of his mind. He and his wife lost their Steels Creek house in the Black Saturday fires. “We’d lived there 25 years,” Dahlstrom says. “We’d had seven years of drought. The trees were dying. You couldn’t have a vegetable garden. For those last few years we kept saying ‘We must move’. Until the decision was made for us.” |

On February 7, 2009, like many people, they stayed to defend their property. When their house became too hot inside, they went outside and watched it burn. They lost everything except the clothes they were wearing. Dahlstrom lost more than 100 paintings – 25 years of work – along with his brushes, paints and canvases. When you commiserate, he points out that people lost their lives.

He painted his first work six weeks later: a chimney in the bush. He called it simply #375, which was their address in Steels Creek. It was a farewell to the house, and a farewell to the bush he had loved and painted for so many years.

And then it was time to move on. In 2010 he and his wife bought a 40-acre block near Inverloch where they agist horses. His studio is a converted shed, which he opens at weekends for visitors.

He’s always painted what he sees around him so now he paints the sea – the surface of the sea and what’s below – but his concerns about climate change are never far away.

“The creation of a ‘pretty picture’ has become secondary in importance to that of raising issues about the causes of change to our environment,” he states on his website.

Were his paintings always political?

He considers the question. “I wouldn’t say political. Perhaps commentary. They make a point.”

But not all of them. Sometimes a painting is just a painting. In the current exhibition, he has a couple of blue-on-blue paintings of fish and jellyfish that he painted because he wanted to use Prussian blue.

“There’s no statement, just the use of a different colour." He stands, head to one side, considering Journey to Prussia as if for the first time. “See how it’s almost black in places?”

He’s painted the Phillip Island shearwaters – “that’s been my bread and butter; that’s been good” – and he did a series of four or five paintings called Bunurong Mistique.

He smiles. “People buy them for their new houses. They bring along their tape measure and look for one that will match the décor.” He's a serious painter, but not a precious one.

A Legacy for the Ocean: Paintings by Ray Dahlstrom. Wonthaggi Artspace Gallery, 7 McBride Avenue, March 16- April 7

He painted his first work six weeks later: a chimney in the bush. He called it simply #375, which was their address in Steels Creek. It was a farewell to the house, and a farewell to the bush he had loved and painted for so many years.

And then it was time to move on. In 2010 he and his wife bought a 40-acre block near Inverloch where they agist horses. His studio is a converted shed, which he opens at weekends for visitors.

He’s always painted what he sees around him so now he paints the sea – the surface of the sea and what’s below – but his concerns about climate change are never far away.

“The creation of a ‘pretty picture’ has become secondary in importance to that of raising issues about the causes of change to our environment,” he states on his website.

Were his paintings always political?

He considers the question. “I wouldn’t say political. Perhaps commentary. They make a point.”

But not all of them. Sometimes a painting is just a painting. In the current exhibition, he has a couple of blue-on-blue paintings of fish and jellyfish that he painted because he wanted to use Prussian blue.

“There’s no statement, just the use of a different colour." He stands, head to one side, considering Journey to Prussia as if for the first time. “See how it’s almost black in places?”

He’s painted the Phillip Island shearwaters – “that’s been my bread and butter; that’s been good” – and he did a series of four or five paintings called Bunurong Mistique.

He smiles. “People buy them for their new houses. They bring along their tape measure and look for one that will match the décor.” He's a serious painter, but not a precious one.

A Legacy for the Ocean: Paintings by Ray Dahlstrom. Wonthaggi Artspace Gallery, 7 McBride Avenue, March 16- April 7