Director Sophie Cuttriss: “Women view the experience of war quite differently.”

Director Sophie Cuttriss: “Women view the experience of war quite differently.” Sophie Cuttriss jumped at a chance to direct the anti-war Minefields and Miniskirts in the Vietnam Veterans Museum.

By Gill Heal

PHOTOS of the massive crowds that occupied the city streets in 1970 tell us a lot about the peace marchers who took part in Melbourne’s anti-Vietnam moratoriums. There’s excitement on those faces and pride, and a sense of newly discovered power – the intoxicating experience of democracy at work as 100,000 people call for an end to the war and conscription.

The Vietnamese War cost the lives of 520 Australians and injured more than 3000. Yet, sitting on hard bitumen, cushioned by the righteousness of our position, we protesters felt little sympathy for our forces in Vietnam. They were on the other side of a bottomless chasm. We couldn’t begin to understand each other.

By Gill Heal

PHOTOS of the massive crowds that occupied the city streets in 1970 tell us a lot about the peace marchers who took part in Melbourne’s anti-Vietnam moratoriums. There’s excitement on those faces and pride, and a sense of newly discovered power – the intoxicating experience of democracy at work as 100,000 people call for an end to the war and conscription.

The Vietnamese War cost the lives of 520 Australians and injured more than 3000. Yet, sitting on hard bitumen, cushioned by the righteousness of our position, we protesters felt little sympathy for our forces in Vietnam. They were on the other side of a bottomless chasm. We couldn’t begin to understand each other.

We were lousy winners. When the war ended and those service men and women were discharged, they were told to disappear, to make themselves invisible to avoid hecklers. They remained off the radar of public consciousness until, decades later, reports of failed marriages, suicide and mental illness culminated in the disastrous statistics associated with post-traumatic stress disorder – a condition affecting almost one third of the 50,000 Australians who served in Vietnam.

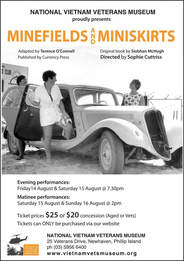

The play Minefields and Miniskirts takes us behind the statistics and confronts us with the stories of real people. Adapted by Terence O’Connell from Siobhan McHugh’s collection of interviews with more than 50 Australian women, it sheds a steady light on the human cost of the war and a nation’s neglect.

O'Connell’s adaption gives us five representative characters: the Correspondent, the Entertainer, the Nurse, the Volunteer and the Vet's Abused Wife. Their monologues are interspersed with songs from the `60s and `70s. These five channel the impact of the war on women.

Wonthaggi Theatre Group stalwart Sophie Cuttriss saw a production of the play at Warragul a decade ago and was deeply moved by it. She thinks there is much to learn from the women’s perspective of war. “We don’t appreciate how much women are damaged by war,” she says. “They view the experience quite differently.”

AS director of WTG’s 2011 production of the play, and aware of the enormous sensitivities involved, Sophie was apprehensive about how the Vietnam veteran community would respond. She needn’t have worried. Veteran’s wives confirmed that it told their stories. And inevitably, in telling their own stories, they tell those of men as well. A Green Beret in the front row wept. He came back a second time and spoke to the cast. The production had achieved something authentic and true.

“I was humbled by the response of the audience,” admits Sophie. “We had audiences that didn’t make a sound, except a laugh or a sob.”

This year’s production of Minefields and Miniskirts is a fundraiser auspiced by the National Vietnam Veterans’ Museum at Newhaven. When sales executive Sonia Hogg approached the WTG with the idea of performing the play in the museum, Sophie put her hand up. She was daunted but, she said, “I’d learnt that if I turn down an opportunity because of fear then I miss out on all sorts of experiences.” And she wanted to support the museum.

Bass Coast composer/conductor Larry Hills was available, as were all but two of the original cast. “The stars must have been in alignment,” Sophie says.

Lighting designer John Cuttriss is enjoying the spatial challenges, taking advantage of the museum’s infrastructure by hanging lights from steel pipes. “The set is minimal but atmospheric,” Sophie says. “We’ll be performing in front of two helicopters. The strength of the play is in the stories and how they’re told.”

Sophie is interested in how the closer physical proximity of the audience in this production will play out for the actors. “In the first production at the Arts Centre, we knew that some stories were distressing but we were separated to a degree.” Ultimately, she says, this is an anti-war play. “The human cost is horrendous regardless of what side you’re on.”

But this is also a play about survival, the ability of people to maintain their compassion and humour, to manage their lives when they return from the war, to find a way of managing that damage. “They’re not the same person. They’ve grown stronger, more resilient; their priorities have changed. They’re more tolerant.”

In leading us to be more mindful and compassionate, Minefields and Miniskirts is important theatre. But perhaps it might do more. There’s a danger in thinking that understanding the pain is enough, that we just have to understand that war has terrible costs. It’s not enough.

The real danger lies deeper: it’s in our readiness to see threat where there is just difference, in our unwillingness to build bridges across the gaps that loom between us. Can Minefields and Miniskirts change this for us?

The play Minefields and Miniskirts takes us behind the statistics and confronts us with the stories of real people. Adapted by Terence O’Connell from Siobhan McHugh’s collection of interviews with more than 50 Australian women, it sheds a steady light on the human cost of the war and a nation’s neglect.

O'Connell’s adaption gives us five representative characters: the Correspondent, the Entertainer, the Nurse, the Volunteer and the Vet's Abused Wife. Their monologues are interspersed with songs from the `60s and `70s. These five channel the impact of the war on women.

Wonthaggi Theatre Group stalwart Sophie Cuttriss saw a production of the play at Warragul a decade ago and was deeply moved by it. She thinks there is much to learn from the women’s perspective of war. “We don’t appreciate how much women are damaged by war,” she says. “They view the experience quite differently.”

AS director of WTG’s 2011 production of the play, and aware of the enormous sensitivities involved, Sophie was apprehensive about how the Vietnam veteran community would respond. She needn’t have worried. Veteran’s wives confirmed that it told their stories. And inevitably, in telling their own stories, they tell those of men as well. A Green Beret in the front row wept. He came back a second time and spoke to the cast. The production had achieved something authentic and true.

“I was humbled by the response of the audience,” admits Sophie. “We had audiences that didn’t make a sound, except a laugh or a sob.”

This year’s production of Minefields and Miniskirts is a fundraiser auspiced by the National Vietnam Veterans’ Museum at Newhaven. When sales executive Sonia Hogg approached the WTG with the idea of performing the play in the museum, Sophie put her hand up. She was daunted but, she said, “I’d learnt that if I turn down an opportunity because of fear then I miss out on all sorts of experiences.” And she wanted to support the museum.

Bass Coast composer/conductor Larry Hills was available, as were all but two of the original cast. “The stars must have been in alignment,” Sophie says.

Lighting designer John Cuttriss is enjoying the spatial challenges, taking advantage of the museum’s infrastructure by hanging lights from steel pipes. “The set is minimal but atmospheric,” Sophie says. “We’ll be performing in front of two helicopters. The strength of the play is in the stories and how they’re told.”

Sophie is interested in how the closer physical proximity of the audience in this production will play out for the actors. “In the first production at the Arts Centre, we knew that some stories were distressing but we were separated to a degree.” Ultimately, she says, this is an anti-war play. “The human cost is horrendous regardless of what side you’re on.”

But this is also a play about survival, the ability of people to maintain their compassion and humour, to manage their lives when they return from the war, to find a way of managing that damage. “They’re not the same person. They’ve grown stronger, more resilient; their priorities have changed. They’re more tolerant.”

In leading us to be more mindful and compassionate, Minefields and Miniskirts is important theatre. But perhaps it might do more. There’s a danger in thinking that understanding the pain is enough, that we just have to understand that war has terrible costs. It’s not enough.

The real danger lies deeper: it’s in our readiness to see threat where there is just difference, in our unwillingness to build bridges across the gaps that loom between us. Can Minefields and Miniskirts change this for us?