For Sheridan Palmer, the South Gippsland coast provided the ideal setting to write about art and the getting of wisdom.

By Sheridan Palmer

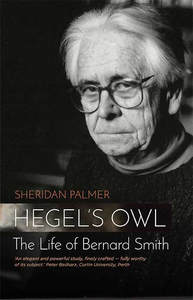

FOR almost 25 years I have been coming to Venus Bay, a jewel of a place nestled in the coastal sand-dunes, where the right measure of unencumbered space, tranquillity and inspiration allows me to engage with the rigours of writing. To tell you about my latest book, Hegel’s Owl: The Life of Bernard Smith, a biography of the great Australian art and cultural historian who died in 2011, I have chosen a story I uncovered during my research. It seems a fitting way of connecting my work on Smith with that pervasive and magnificent force of nature that we know so well here on the South Gippsland coast, the sea.

The story involves a famous poem by Samuel Coleridge, ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’, which narrates the dramatic story of sailors who venture through stormy and becalmed seas before entering the South Pacific and treacherous waters of the Antarctic. Some of you may be familiar with its famous rhyme that utterly captures the perils of being adrift on the ocean.

Water, water every where

Nor any drop to drink

But what is the connection between this poem and Bernard Smith? In 1949 when he was cataloguing some 3000 drawings by artists on Captain James Cook’s voyages of discovery, including the landing on the east coast of Australia – and remember there were no cameras then and artists were trained to accurately paint the people, birds, fish and the weird animals of the southern hemisphere – Smith came across the astrologer William Wales who sailed with Cook on his first voyage in 1767.

Some years later he discovered Wales’s sea journal in the Mitchell Library, Sydney, and was struck by the similarities between Coleridge’s poem and the conditions described by Wales as they sailed into the great southern seas. When Wales retired from the navy he taught mathematics to the young Coleridge—and it was his dramatic sea-faring stories, Smith argues, that filtered into the ‘Rime of the Ancient Mariner’. Wales regaled his students with tales of storms that drove them southwards where they encountered terrible fogs and floating ‘ice islands’ or giant icebergs, which cracked and split apart like thunder, and the great Albatross, a bird they unfortunately regarded as a bad omen and shot or caught for food. As Coleridge wrote:

The ice was here, the ice was there

The ice was all around:

The poem is long and for reasons of space I cannot say more about its riveting effect but it is one example that reveals Bernard Smith’s extraordinary ability to find connections that unite historical moments. Moreover, we tend to forget those stories of bravery, tragedy and the history of sailors who ventured through these southern waters centuries ago.

But why did I call the biography ‘Hegel’s Owl’? Well, Bernard Smith believed that events could not be properly understood without a certain temporal distance. He was fond of quoting Hegel, the German philosopher, who wrote, “The owl of Minerva spreads its wings with the falling of the dusk”. (Minerva was the goddess of art and war and her owl epitomises wisdom). As it flies off at dusk and looks back over the events of the day, a rear-view mirror of what has gone before, things can be seen and understood more clearly. It is why Smith asked me to write his life story, he did not have enough distance between himself and his past.

Smith’s reputation as a giant in both Australia and the international world of art is without peer, and the biography became a consuming labour of six years, with many months spent in libraries and archives here and in Britain, trundling through cities and museums in which Bernard Smith had lived and worked, and meeting and interviewing hundreds of people who had known him – indeed, Robert Smith, who gifted his remarkable art collection to Wonthaggi last year was a close associate of Bernard Smith.

Smith’s life was complex; he was born illegitimate in 1916, raised as a ward of the State, and against all odds rose rapidly in education and as a critic of art and society. His first acclaimed book was written in 1945 just as the Second World War ended, and his final book was published in his 91st year, in 2007. In between he had been involved with Communism, tackled cultural imperialism and politics, taught and wrote about art and mused on the impact of British and European traditions in Australia, from the time of colonial settlement until contemporary times. In 1980, he turned his mind to Australia’s Indigenous situation and gave a brilliant series of ABC Boyer lectures, broadcast and published as The Spectre of Truganini, in which he called for the urgent recognition of Indigenous culture and the reparation of Aboriginal rights.

While working on this biography I came as often as I could to my beach house at Venus Bay. The sound of pounding surf, the wild winds, the wonderful coastal landscape, smell of salt air was a perfect background to the rigours of writing and, importantly, it gave me the distance to think, reflect and write clearly.

Sheridan Palmer is an art historian, curator and writer. She wrote Dean Bowen: Argy Bargy, 2007; Centre of the Periphery: Three European Art Historians in Melbourne, 2008; and Hegel’s Owl: The life of Bernard Smith, 2016.

FOR almost 25 years I have been coming to Venus Bay, a jewel of a place nestled in the coastal sand-dunes, where the right measure of unencumbered space, tranquillity and inspiration allows me to engage with the rigours of writing. To tell you about my latest book, Hegel’s Owl: The Life of Bernard Smith, a biography of the great Australian art and cultural historian who died in 2011, I have chosen a story I uncovered during my research. It seems a fitting way of connecting my work on Smith with that pervasive and magnificent force of nature that we know so well here on the South Gippsland coast, the sea.

The story involves a famous poem by Samuel Coleridge, ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’, which narrates the dramatic story of sailors who venture through stormy and becalmed seas before entering the South Pacific and treacherous waters of the Antarctic. Some of you may be familiar with its famous rhyme that utterly captures the perils of being adrift on the ocean.

Water, water every where

Nor any drop to drink

But what is the connection between this poem and Bernard Smith? In 1949 when he was cataloguing some 3000 drawings by artists on Captain James Cook’s voyages of discovery, including the landing on the east coast of Australia – and remember there were no cameras then and artists were trained to accurately paint the people, birds, fish and the weird animals of the southern hemisphere – Smith came across the astrologer William Wales who sailed with Cook on his first voyage in 1767.

Some years later he discovered Wales’s sea journal in the Mitchell Library, Sydney, and was struck by the similarities between Coleridge’s poem and the conditions described by Wales as they sailed into the great southern seas. When Wales retired from the navy he taught mathematics to the young Coleridge—and it was his dramatic sea-faring stories, Smith argues, that filtered into the ‘Rime of the Ancient Mariner’. Wales regaled his students with tales of storms that drove them southwards where they encountered terrible fogs and floating ‘ice islands’ or giant icebergs, which cracked and split apart like thunder, and the great Albatross, a bird they unfortunately regarded as a bad omen and shot or caught for food. As Coleridge wrote:

The ice was here, the ice was there

The ice was all around:

The poem is long and for reasons of space I cannot say more about its riveting effect but it is one example that reveals Bernard Smith’s extraordinary ability to find connections that unite historical moments. Moreover, we tend to forget those stories of bravery, tragedy and the history of sailors who ventured through these southern waters centuries ago.

But why did I call the biography ‘Hegel’s Owl’? Well, Bernard Smith believed that events could not be properly understood without a certain temporal distance. He was fond of quoting Hegel, the German philosopher, who wrote, “The owl of Minerva spreads its wings with the falling of the dusk”. (Minerva was the goddess of art and war and her owl epitomises wisdom). As it flies off at dusk and looks back over the events of the day, a rear-view mirror of what has gone before, things can be seen and understood more clearly. It is why Smith asked me to write his life story, he did not have enough distance between himself and his past.

Smith’s reputation as a giant in both Australia and the international world of art is without peer, and the biography became a consuming labour of six years, with many months spent in libraries and archives here and in Britain, trundling through cities and museums in which Bernard Smith had lived and worked, and meeting and interviewing hundreds of people who had known him – indeed, Robert Smith, who gifted his remarkable art collection to Wonthaggi last year was a close associate of Bernard Smith.

Smith’s life was complex; he was born illegitimate in 1916, raised as a ward of the State, and against all odds rose rapidly in education and as a critic of art and society. His first acclaimed book was written in 1945 just as the Second World War ended, and his final book was published in his 91st year, in 2007. In between he had been involved with Communism, tackled cultural imperialism and politics, taught and wrote about art and mused on the impact of British and European traditions in Australia, from the time of colonial settlement until contemporary times. In 1980, he turned his mind to Australia’s Indigenous situation and gave a brilliant series of ABC Boyer lectures, broadcast and published as The Spectre of Truganini, in which he called for the urgent recognition of Indigenous culture and the reparation of Aboriginal rights.

While working on this biography I came as often as I could to my beach house at Venus Bay. The sound of pounding surf, the wild winds, the wonderful coastal landscape, smell of salt air was a perfect background to the rigours of writing and, importantly, it gave me the distance to think, reflect and write clearly.

Sheridan Palmer is an art historian, curator and writer. She wrote Dean Bowen: Argy Bargy, 2007; Centre of the Periphery: Three European Art Historians in Melbourne, 2008; and Hegel’s Owl: The life of Bernard Smith, 2016.

Hegel's Owl is on sale at Wonthaggi Art Space, Kilcunda Store, Meeniyan Art Gallery, Koonwara Store and the Thirsty Work Gallery at Tarwin Lower.