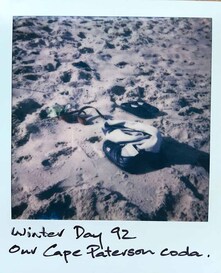

| By Rees Quilford Each day of our first COVID winter I left the warmth of our new home, meandered through sleepy streets, over the dunes, down to the same secluded stretch of sand that marks the threshold between shore and sea. I walked the vacant coastline then dove into the bracing cold to swim in the sea. Every day of that arduous winter, all ninety-two of them, I returned to the same place in search of something different. Once there, I sought to reconnect with that once familiar place. The shoreline I visited is a place of my childhood and adolescence, the Cape Paterson Bay Beach, the unobtrusive shoreline of a quiet seaside village in the heart of Victoria’s Bass Coast. It’s a haunt I’ve known since birth, one that elicits fuzzy recollections of sunburnt skin, chapped zinc smeared lips, and dawdling fishing. |

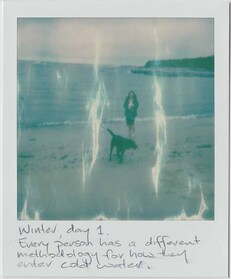

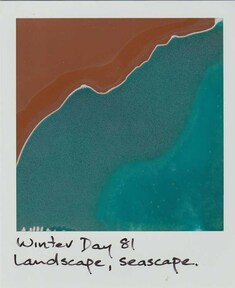

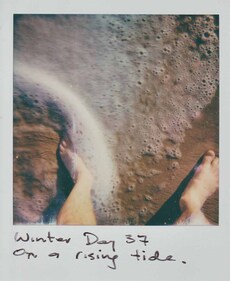

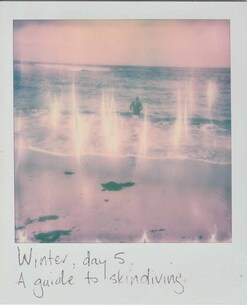

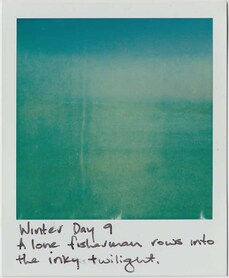

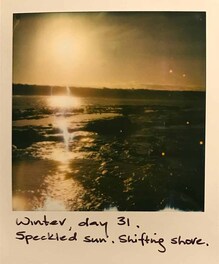

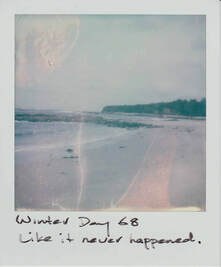

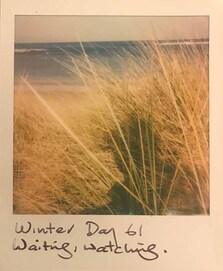

In times of extraordinary disruption – when the COVID pandemic has shadowed the firestorms and smouldering dirt of the summer before – it’s comforting to gravitate toward the familiar. We always look to the places and things we know so as a saltwater person, one born of this coast, I turned to the water and the sand in search of reassurance. At this bedrock place, I followed an impulse toward the icy embrace of the ocean and tried to make some sense of the grim new realities that face us all. Each day, I turned to lonely stretches of sand and wild oscillating weather. I immersed myself in frigid waters, I walked, and I watched. Then, with an old Polaroid camera found in a local junk shop, I photographed something of what is a beguiling place. The picture I would subsequently annotate by hand with a scrawled note or reflection. Those images – 92 inscribed portraits of place – form a diary of sorts, one that documents and reflects. A chronicle marking time spent at the beach during a winter of relentless disruption.

By reacquainting with this place – one that I had once known so well – I aimed to reconnect, to reorient. I hoped time spent in cold waters and on lonely sands would provide knowledge and insight. I hoped it would afford an avenue to see a particular place and the world, in a different light. I hoped that viewpoint would provide a counterpoint to ceaseless screen-time and anxious doom scrolling. I hoped it would calm thoughts of fire and plague. Under the pall of multiple existential threats, I sought solace and clarity of thought in the place of my childhood.

The soon-to-be-washed-away poignancy of this sketch resonates. My connection to this beach and the local area is longstanding – I was born and raised here like my father before me – but have lived away for more than twenty years. A quintessentially country upbringing had afforded outdoor freedoms and close-knit community connections, but the approach of adulthood brought with it a compulsion to escape. At seventeen I looked to the city, to university, to travel, and to work for counterpoints to the steady parochialism of country life. Away from family, childhood friends, and the familiar I found my feet. In doing so, I think I managed to graft some semblance of worldliness that I wouldn’t have found otherwise. But now, twenty years on, my partner (who was also born here) and I find ourselves buying a house back where we grew up. Our recent return is one of mixed emotions. On one hand, the abundance of intergenerational associations– intimate connections to things, places, and people – prompt memories and fond nostalgia. Counter to that is the awareness of the underlying conservativism (and on occasion isolationism) that infuses many casual exchanges. I am yet to find my people and place back here – a sense of displacement lingers.

My mind brims with these thoughts as I plunge into the cold blue water. A longing for greater connectedness and knowledge permeates my bare skin to query the salutary depths and I feel the urge to find a precise language to express these feelings. It is these notions that motivate my repeated visits to this beach, where elusive moments of literacy can be found in place. My imagination is stimulated by locative thinking about, and with, the past, the present and the future. This is a place where acts of walking, swimming and observation allow for a form of exchange between self and the landscape (Mills, 2020, p. 128).

The physical and spiritual benefits of cold-water swimming have been espoused by many. Writer and photographer Tasmin Calidas (2020) describes increased emotional resilience, reduced inner silences and closer alignment to the cycles of nature gained through a daily ritual of immersion in the icy Atlantic seas of Scotland’s Hebridean islands. Similar sentiments can be traced back to those made by Australia’s mermaid, the star actress Annette Kellerman, who described the great debt she owed to swimming in her best-selling 1918 instructional manual How to Swim. Water-feat vaudeville and open water competitions brought her good health and fame but also nurtured a childlike curiosity as well as a modesty of the soul (pp. 15,36). Another more contemporary great of Australian swimming, Ian Thorpe, argues for intimate and reciprocal relationships between swimmers and the water saying, “when we swim, we need to collaborate with the water in the search for the perfect movement, to accommodate it rather than resist it” (Thorpe cited in Bürklein, 2016).

Amy, Nahla and I share aspirations similar to those described by Calidas, Kellerman and Thorpe. While the methodologies we adopt when first connecting with the sea differ greatly, all three of us leave the water invigorated and more attuned to our surrounds. The exhilarating experience of immersing our bodies and souls provides a tantalising glimpse of a clarity of thought that has been hitherto absent.

Standing atop the clifftop, I watch that stranger regard the ocean as it batters the beaches and rock. An old man and the sea. Taking his lead, I walk down the hill, an old man, looking to dive into that bitter sea.

It was also an arena for vicious fights, bullying and venomous masculinity. Young men drinking too much and punching on. The old would bully the young, the big dominate the small. I remember one night in the late summer, early autumn even, when a young man – must have been in his early twenties – copped one of the worst beatings I’ve ever witnessed. It was delivered by a much younger boy, but one who had been made hard early, one who knew how to fight. I remember the pack of kids goading him into delivering that belting. Fuelled by testosterone, booze, insecurity, and naivety the mob – me included – watched and howled at the spectacle. After the blows had been exchanged, the blood had been spilt, and the wounded were dragged away, I remember wondering how those two kids felt, subjected as they had been to such harried objectification. I’m sure I didn’t think of it in those terms, but I was aware of the brutal manipulation that had transpired. The bloke who copped the beating would have woken sore and ashamed, but the other kid – who was a slightly younger mate – would have also shared that shame. It would have been humiliation of a different kind, but one felt no less keenly. My friend was a good kid, but his life had been difficult, he didn’t deserve our provocations just as the other man didn’t deserve the beating.

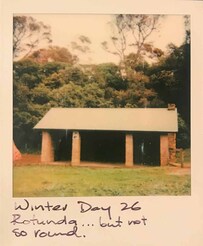

Some of those kids, mates I spent summers drinking and mucking about with, haven’t fared so well. Many have struggled with the messy complexities of adult life. At least three committed suicide as young men. Messed up but fundamentally good-natured people who couldn’t find their way beyond their immediate confusion and troubles. I was one of the lucky ones. I managed to escape, found my feet and a different life in the city. But returning to this place, to this Rotunda, more than twenty years on I see their faces etched with youthful exuberance, cheeks flushed from three cans of beer. They are frozen in time, etched in memory – young, beautiful, and wild – while I have grown older, greyer, wearier.

Today I’ll photograph a beguiling formation that occupies part of the nearby rock platforms. Carved by the waves, the rain, and the wind, it bears a striking similarity to a human heart. A minute fragment of Nature presenting as Art. I’ve tried to photograph it previously, but each polaroid returns blurry as if resistant to being pinned down. Today is no different but that seems apt – reflective of ephemeral thoughts.

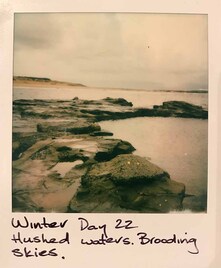

Staring out to sea, I always look to the horizon, where the ocean meets the heavens. The enormity of the world and my infinitely small role in it never fails to overwhelm. Never fails to bring humility. This feeling is especially acute beneath overcast skies when great walls of clouds bleed into the reflective ocean. There I am privy to the briefest glimpse of something that eludes the day-to-day banality of our always limited understanding. Something akin to a line I recently read in a short story, “the something before the everything, its boiling fronts forcing life and space and time into nothingness. True no-thingness” (Gildfind, 2018, pp. 15-16).

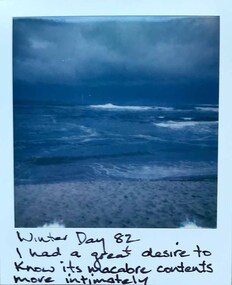

Today feels infinitely frostier than the days and weeks prior. The cold seeps through my skin, lodges deep in my joints and bones. As the cleansing cold overwhelms my senses the ability to mark time deserts me. I force myself to linger, submit, until the discomfort is replaced by comforting numbness. An inordinate amount time later (likely just a matter of minutes) I waddle out shivering. The grim ferocity of this wild seascape is enthralling, seemingly reflective of the ferocity with which COVID is wreaking indifferent havoc across the globe. I am possessed by a great desire to know the macabre contents of this place more intimately. Numerous lives are lost in these waters every year, fishermen washed from the rocks, swimmers and divers drowned. And that is just the human loss, death and decay are evident everywhere – in the occasional fish carcass or jellyfish lying at the water’s edge, in a feather found in the dunes, in the technicoloured array of shell and rock fragments that decorate the shore break. While joy can be located in the stunning natural splendour of this place, beauty and empathy can also be found in its never-ending cycles of death, decay and renewal.

I found myself reflecting. I thought and pondered, speculated on ontological things – life after death, climate change, corruption, inaction, my inability to concentrate for any extended period of time. Winter would soon be upon us. My thoughts turned to the people that have trod this land before me. The indigenous custodians of these unceded lands and seas, the Yallock-Bulluk of the Bunurong. I thought of generation upon generation who have swum this ocean, of the people who might tread its sands after me. I thought of waters that surround me and all of the actors, living and inanimate, that call it home. A forgotten titbit came to mind, that just like birds, fish sing to the skies above (Keenan, 2016). When I finally emerged shivering from that cold uncaring sea, I looked at the clifftops, where the earth assembles with the heavens, and beheld a world full of possibilities.

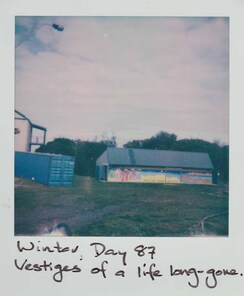

Given the inherently subjective and introspective nature of this collection, the motivation underpinning its compilation needs to be unpicked. I see it as an attempt to bear witness on a particular place at a particular time. It is an act of documentation, one capturing my experience of returning to the place of my childhood after many years away, one capturing the turning of a season and the urgency of our time. Returning to the same place each and every day, I have aimed to capture a different aspect – from jagged shores to vestiges of beach life long gone – in the hope that someone else, somewhere else, some other time, might glean some insight, pleasure or apperception from these records.

A familiar face distracts me as I leave the water. Now in his mid-fifties, Gary has lived here most of his life. We stand in the shallows while the early winter sun warms our backs. COVID is the first topic of discussion, we speculate on likely timeframes, the fall-out, and vaccines, “We couldn’t pick a better place to see out something like this,” he says. Talk moves to mutual acquaintances, life in the country, and being out of work. The company that Gary had worked with for the majority of his professional life was restructured a couple of years back, forcing semi-retirement upon him earlier than he’d planned. He’s philosophical about it, looks to spend that extra time wisely. Today, that means a spot of snorkelling. Exchanging farewells, I walk up the beach feeling optimistic. Gary’s hopefulness is infectious. As I towel myself down, I watch him don his mask and snorkel then swim out into the bay, making his way over those reefs and crevices. I’ll soon be out of work, but as Gary pointed out, we are the fortunate few, we’re here, in this beautiful place.

The low infection numbers here in regional Victoria mean we currently enjoy relative freedom – of movement and from fear. However, the bewildering intimacy of the calamity engulfing the city can’t be ignored. Everyone is acutely aware of the misfortunes befalling friends, family and colleagues. Those living just fifty kilometres up the road are in hard lockdown. In his poetic mediation On Listening, Martin Flanagan reflects on the damage caused by retributive banishment:

| If you find your sense of self, your meaning, through other people and those other people banish you, there is a pain I can only describe as existential. (Flanagan, 2016, p. 13) |

As this scene repeats, I join the cast in the role of swimmer. The etymology of swimming and fishing can be traced to a convergence. The old English word ‘swimman’ – to move in or on the water, to float – comes from older Germanic and Welsh words meaning to be in motion. While cognates in Old Irish ‘do-sennaim’ and Lithuanian ‘sundyti’ signify the hunt and the chase.[2] Solitude and peace can be found in fishing just as in swimming.

Teenage summers spent at this beach – long hot days progressing through nippers onto a bronze medallion as well as nights spent camped out in the dunes – have created great fondness for this place. It’s sad to see the clubhouse in such disrepair. After the flood, a friend posted photos from the 1960s showing the former clubhouse equally devastated by flood but looking through the records reveals that place has flooded at least three times in the past decade. Our memories are short when it comes to these things but those once vibrant buildings of the lifesaving tower – which have hosted generations of sunburnt kids, weddings, dances, birthday parties and hole-in-the-wall kiosks – now cut forlorn figures. The intimacy of the destruction wrought by COVID has dulled the immediacy of the longer-term threat posed by climate change. But these condemned buildings – vacant and unused – offer immediate and tangible evidence of the imminent climate emergency playing out before our eyes. I wonder what the next generation of life savers – our children’s children – will make of our role in it all.

My increasing acclimatisation to the cold doesn’t offer any comfort from the shock of the announcement we were dreading. Rising COVID-19 infections and untraceable community transmission has halted any thought of eased restrictions. Instead, home visitation and outdoor gatherings will be further reduced. People are on edge. The complacent optimism about virus control has vanished. A long and wretched haul awaits.

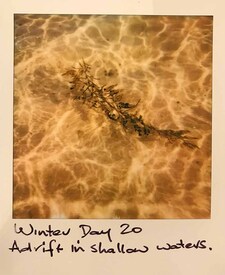

After hearing the infection announcement, I make my way to the beach. There isn’t a breath of wind, but a taciturn frostiness persists. Irrespective of that, I manage to find a glimmer of hope in a seemingly innocuous feature. A knot of sea kelp floating near the shoreline grabs my attention – offers itself up as proof that the natural world continues oblivious to our ill-gotten realisations. In her evocative literary examination of how the delicate landscapes around the North Sea act as bellwethers for environmental concern, Katie Ritson points out that any uncertainty about what we humans unleash is offset by a sure knowledge that the agency of the natural world will outlast our own (2018, p. 2). That kelp, adrift in shallow waters, is illustrative of Ritson’s confronting yet strangely comforting insight. It also reflects the COVID situation facing us here Victoria, untethered as we are, in dangerous waters.

This beach has long been a place of escape. It’s one of the many coastal bays on which miners and their families sought refuge from the black dust, toil and sweat of the State Coal Mine. Just five miles from Wonthaggi, Cape Paterson’s beaches offered convenient escape from the hustle and bustle of the town. The ramshackle huts that sprung up around the Bay allowed weekends and summers to be spent swimming, fishing, and relaxing. Those shacks are long gone now, demolished by order of the Lands Department in the mid-1950s (Hayes, 1998), but hints and traces of them still remain. One obvious signpost is a road atop the cliff called Hut View, but another recognisable cue is the manmade lido in the Bay’s centre.

A surge in the popularity of swimming in the early twentieth century led to a wave of construction where amenable sites on lakes, rivers and the ocean were re-shaped as open-air pools. Architectural Historians Hannah Lewi and Christine Phillips frame this as a potent example of modern design’s ambitions to refashion the natural environment to make it accessible for leisure and recreation (2013, p. 281). Cape Paterson was no different. An enterprising group of local coal miners and volunteers from the lifesaving club embraced that modernist inclination in the 1950s—armed with picks, shovels and concrete they engineered a predictable and safe swimming retreat in the rocky outcrop in the centre of the bay. About twelve metres long, three metres wide and a metre deep, the Cape Paterson rockpool remains a beacon for kids and adults alike.

Place, seen through the lens of identity, contemplation and environmental attentiveness, is a site of meaning making but also one with ethical obligations. Advocating for the revival of storied and nuanced senses of land and place, the Australian philosopher and ecofeminist Val Plumwood (2008) highlights the problematic propensity to privilege certain places at the expense of others. Special places – such as this bay – capture our interest, demand attention, and are delineated from our ecological footprint. These places are maintained at the expense of ‘shadow places’, overlooked, unacknowledged and neglected spaces degraded in service of those privileged places. The council bins lining the beach carpark provide a clue to these spaces. Marshalling points for the waste consumed during the usage of this place, cast-offs to be whisked out of sight and dumped in landfill elsewhere. Those sandy jocks carelessly left lying behind will ultimately end up at another unknown and unacknowledged place. A shadow place forced to bear the ecological footprint of this beach and its activities.

Looking at those bins, I am struck by the introspective self-indulgence of my visitation and documentation process. Maintaining a routine of swimming, walking and reflection in this beautiful and safe place during a time of mass disruption and suffering suddenly seems a product of unearned privilege and accidental good fortune. I know I can’t change those things, but providence brings with it an obligation to tread lightly and to utilise this privilege for meaningful and useful ends. I try to bear that in mind when walking these sands and swimming in this sea.

A handsome gloaming lights the clifftop, fading light dancing betwixt sea and sky. I turn to the polaroid to capture that magic, quick snaps – one of the clifftops and the other of the rotunda park bathed in artificial light from a lone streetlamp. The sight takes me back to the R.E.M song:

| The photograph on the dashboard, taken years ago Turned around backwards so the windshield shows Every streetlight reveals the picture in reverse Still, it's so much clearer I forgot my shirt at the water's edge The moon is low tonight (R.E.M., 1992) |

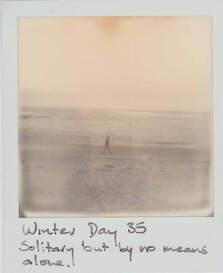

I wait patiently. A beat follows the beat before. The boy walks into shot, one framed by the bay. Depressing the button, the polaroid mechanism whirs to life. A dark silhouette is captured mid stride, head slightly bowed, alone in that bordered view with only the calm grey ocean at his back for company. Solitary but by no means alone seems an appropriate summation of the situation, reflective of the one in which we all find ourselves.

One of the Seven Sages of Greece, Thales of Miletus, hypothesised water to be the originating principle of nature, a classical element, the essential substance of matter. Water, within this understanding, is the element from which all else is derived (Aristotle, 2018, pp. 8-9). While modern science no longer maintains classical elements as the material basis of the physical world, there is no denying that the sea in which I swim is millions of years old. Ancient water that seeps through your skin. A tangible reminder of the multifaceted permeability of people, place and history. Deborah Bird Rose discusses this permeability in relation to notions of belonging here in Australia. Citing the much-used pastoralist trope of the land literally seeping into the blood – an ambit claim that intrinsically ties one’s blood, sweat and tears to the fertility of the land – she highlights the paradox:

| that the country that gets into people’s blood invariably contains the blood and sweat of Aboriginal people as well as settlers. It may contain convict blood, and the remains of the dead. It will contain the blood of childbirth, and the blood and bones of massacres. It will contain the remains of animals, of extinct species, perhaps. (Bird Rose, 2002, p. 321) |

Those utterly terrifying revelations have been rendered insidiously distant by the immediacy of rising COVID infections and today’s chilly rain. Relishing the change, I wait for a proper deluge before venturing to the beach. I hurry over the soddened sand. A deserted beach cast in a blackish hue by the pall of cold droplets falling from the heavens. That rain stings my bare skin as I dawdle in waist deep water. I love swimming in the rain – it’s one of life’s great joys. As the familiar icy embrace envelopes me, I watch the rain meet the sea. Millions upon millions of tiny little collisions rippling on the surface around me. Beauty and brilliance in each collision. Lingering to bear witness I wonder how this pandemic is obscuring the urgency of global warming – the most significant threat to our long-term survival.

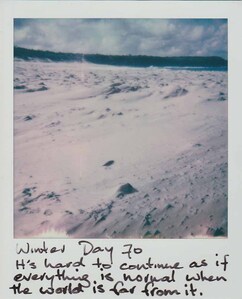

I strip off and dive in the water. Encircled by the bracing cold I look to the expansive sky and wonder what my 17-year-old self would have made of this shitshow. Today’s newspaper carries a collection of vignettes from children and teenagers reflecting on the impact of COVID. The poignancy of one in particular stands out:

Mourning VCE year

I’m upset and disappointed. I’m

mourning the loss of what should

have been one of the best years of

my life. Year 12 is traditionally full

of learning, celebration, connec-

tion – a rite of passage taken away

from us. There are people much

worse off than I am, and I know this

is for the best, yet I can’t help but

feel the loss of what this year

should have been. It’s hard to stay

motivated and continue our stud-

ies on The Crucible and matrices as

if everything is normal, when the

world is far from it.

Emma Christina, 17, Lysterfield

(cited in Prytz, 2020)

‘It’s hard to continue as if everything is normal, when the world is far from it,’ a sentiment one can’t help but wholeheartedly agree with.

I have come to realise that this process – encompassing as it does a routine of walking, swimming, and watching – is an exercise in personal reflection. Not just documentation for the sake of posterity, but an act that attempts to capture an exceptionally significant nexus of historical, contemporary, and natural forces. Observing this from the place of my childhood and adolescence, I have tried to pay particular attention to the natural world. Thus far, I am constantly reassured by the unequivocal disinterest it has for the current state of human affairs.

The act of reacquainting myself with Cape Paterson’s Bay Beach has provided a way to reconnect, prompted a grounding through which to see my relationship to place, and the world, in a different light.

[1] Despite its rectangular layout, the building was always known as the Rotunda. Built in 1954 by volunteers from the Wonthaggi Lifesaving Club, the structure is made from the same hand cast bricks used for the adjacent community hall. See https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=3548299201858415&set=pcb.976944369384145 for newspaper articles recounting the 1954 community working bees making bricks.

[2] Etymology of swim (verb): The old English word ‘swimman’ means, to move in or on the water, to float, comes from an older Germanic word (swem) / older Welsh word (chwyf "motion") meaning to be in motion. Old Irish (do-sennaim) meaning I hunt. Lithuanian (sundyti) meaning to chase.

ANU. (2019). ANU climate tool identifies end of winter by 2050. Retrieved from https://www.anu.edu.au/news/all-news/anu-climate-tool-identifies-end-of-winter-by-2050

Aristotle. (2018). The Metaphysics (J. H. McMahon, Trans.). Mineola, New York: Dover Publications Inc.

Bird Rose, D. (2002). Dialogue with Place: Toward and Ecological Body. In Journal of Narrative Theory: JNT, 32(Fall), 311-325.

Bürklein, C. (2016). 2016 Biennale. Ian Thorpe for The Pool, Australia. Retrieved from https://www.floornature.com/blog/2016-biennale-ian-thorpe-for-the-pool-australia-11689/

Calidas, T. (2020, Sunday 26 July ). I ran away to a remote Scottish isle. It was perfect. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2020/jul/26/i-ran-away-to-a-remote-scottish-island-it-was-perfect

Calligeros, M., & Dunckley, M. (2020). Worst day: Victoria records 725 new cases of coronavirus, 15 deaths. The Age. Retrieved from https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/worst-day-victoria-records-725-new-cases-of-coronavirus-15-deaths-20200805-p55ip4.html

Flanagan, M. (2016). On Listening. Melbourne, Victoria: Penguin Random House Australia.

Freedman, A. (2020, 24 June 2020 ). Hottest Arctic temperature record probably set with 100-degree reading in Siberia. The Washington Post. Retrieved from www.washingtonpost.com/weather/2020/06/21/arctic-temperature-record-siberia/

Gildfind, H. C. (2018). The Worry Front. Margaret River, W.A.: Margaret River Press.

Hayes, W. R. (1998). The golden coast : history of the Bunurong. Inverloch, Vic: Bunurong Environment Centre, South Gippsland Conservation Society.

Keenan, G. (2016, 21 September 2016). Fish recorded singing dawn chorus on reefs just like birds. New Scientist. Retrieved from https://www.newscientist.com/article/2106331-fish-recorded-singing-dawn-chorus-on-reefs-just-like-birds/#ixzz6d9Ri8Fd0

Kellermann, A. (1918). How To Swim. New York, USA: George H. Doran Company.

Lewi, H., & Phillips, C. (2013). Immersed at the water’s edge: modern British and Australian seaside pools as sites of ‘Good Living’. arq: Architectural Research Quarterly, 17(3/4).

Massey, H., & Scully, P. (2020). How to acclimatise to cold water. Retrieved from https://www.outdoorswimmingsociety.com/how-to-acclimatise-to-cold-water/

Mills, J. (2020). Walking Maps of Bruny Island. Meanjin, Winter, 120-129.

Muecke, S. (2008). Joe in the Andamans and other fictocritical stories. Sydney: Local Consumption Publ.

Murray, P., Munro, K., & Taylor, K. (2020, 31 August 2020). Note to self: a pandemic is a great time to keep a diary, plus 4 tips for success. The Conversation. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/note-to-self-a-pandemic-is-a-great-time-to-keep-a-diary-plus-4-tips-for-success-144063

Plumwood, V. (2008). Shadow Places and the Politics of Dwelling. Australian Humanities Review(44). Retrieved from http://www.australianhumanitiesreview.org/archive/Issue-March-2008/plumwood.html

Prytz, A. (2020, 9 August 2020). Victorian kids share their stories of school life in lockdown 2.0. The Age. Retrieved from https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/victorian-kids-share-their-stories-of-school-life-in-lockdown-2-0-20200806-p55j5l.html

R.E.M. (1992). Nightswimming. On Automatic for the People. New York: Warner Bros. Records.

Ritson, K. (2018). The shifting sands of the North Sea Lowlands : Literary and historical imaginaries. London, Englang: Taylor & Francis Ltd.

Safina, C. (2010). The View from Lazy Point: A Natural Year in an Unnatural World. New York, N.Y.: Henry Holt and Co.