the traditional custodians of the land upon which this narrative is set.

I pay my respects to their elders past, present and emerging

and to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

| By Linda Cuttriss At Screw Creek, in the dead of night on the far edge of town, a man crept silently aboard the Lizzie. His plan was dangerous and risky but he was fed up being paid a pittance for long hours of back-breaking work. This would teach his boss a lesson and settle things once and for all. The sound of the explosion would have boomed across town, rattling windows and shaking the townsfolk from their sleep. There would have been quite a fuss the next day as word got around that Lizzie had been blown to pieces. Many would have known that local man, Jack Graham had the contract to ‘metal’ the ‘all weather’ approaches to Screw Creek bridge just outside of Inverloch and that he was using Lizzie to carry stone upstream from the nearby Cuttriss quarry, but I wonder how many knew of the dispute that had been smouldering. The report in the local newspaper would have kept them guessing: | Bass Coast writer Linda Cuttriss won the 2020 Bass Coast Prize for Non-Fiction with this essay, part true detective story, part local history, part family history. |

I still don’t know if the ‘black trackers’ found any clues when they searched Screw Creek in 1915 or if the locals had more knowledge than they were prepared to tell the authorities. The truth of who destroyed Lizzie remains a mystery.

I first learnt of Lizzie about 20 years ago when my father Len wrote the History of the Cuttriss Family and their connection to the development of Inverloch and District. I had always known that my grandfather was a pioneer of the town and that a street was named after the Cuttriss family. I knew that Grandad was born in the late 1880s and grew up on the far side of Screw Creek, but as a young person I hadn’t thought about his parents and grandparents, what had brought them there and what their lives had been like.

There were stories in Dad’s Family History I had never heard before. My great-great-grandfather had livery stables above Townsend Bluff where travellers used to stay when a rock ford was the only way to get across Screw Creek. My great-grandfather had a quarry and a loading jetty near the mouth of Screw Creek and leased a barge called Lizzie to cart the stone to Tarwin Lower. Perhaps Dad had mentioned these things when I was little and they hadn’t sunk in or perhaps he thought I was too young to have any interest.

When Dad wrote the Family History I was living interstate, bound up in my own life and while I was proud of him for recording our stories I didn’t pay them much attention even when I returned to be closer to Mum and Dad in their later years. That is, until one day in September 2015, about a year before Dad passed away, we were having lunch and got talking about Lizzie. He said he didn’t know who had blown her up but that her ribs could still be seen sticking out of the mud a decade or so earlier. Straight away I said, ‘Let’s go there now and see if we can see her’.

The most accessible place was from a small reserve in the new housing estate on the western bank of the creek. Although Dad reluctantly used a walking stick by then, he seemed to slip through the wire fence with ease. He had been a farmer all his life so a cattle fence was no obstacle, but more than that, we were at Screw Creek, a place that ran deeply through his life and connected us with three generations before him.

We didn’t find any remains of Lizzie that day. The embankment was too steep for Dad to climb down. But the photo of Dad standing there smiling, with the bush reflected in Screw Creek behind him, is one I will always treasure.

As kids, my brothers John and Kevin and I would go adventuring up the back paddocks and often be gone all day. Sometimes we’d scramble through the boundary fence into forbidden territory, exploring along the edge of Screw Creek, venturing under the bridge and into the bush on the other side.

Screw Creek begins somewhere in the paddocks north of the farm and threads through open farmland to the shallow estuary of Anderson Inlet into which the Tarwin River also flows. Her banks are thinly vegetated until she reaches the bridge on Inverloch-Venus Bay Road where her waters are tidal and she is fringed by mangroves, swamp paperbark and eucalypt woodland. Anderson Inlet was named for Samuel Anderson and the township that emerged along its northern shores near the entrance to Bass Strait, around 150 kilometres south-east of Melbourne became known as Inverloch. Screw Creek opens into the Inlet on the eastern edge of town.

I would have thought from an aerial view of Screw Creek, that her name came from the U-shaped bend not far from her mouth, but in a ‘Letter to the Editor’ of the Australasian in 1894, Neno writes from Inverloch that she is named for the call of the wattlebird:

They [wattlebirds] are very numerous on the coast ti-tree, and there is a story told by the older bushmen in this part that Screw Creek, on the old Tarwin Road, derived its name from the call of this bird. They were numerous on its banks, and the stock-boys travelling with cattle to Black’s station on the Tarwin River, used to make this creek their camping place, and roused from their sleep in the mornings thought the cry resembled the words “Screw Creek!” “Screw Creek!” and thus christened the stream.[2]

In 1894, my grandfather would have been six years old, living at the homestead and livery stables on the hill above Screw Creek. He probably also went adventuring with his brother and sister through the bush alongside the creek and would have known of the stock-boys’ camp and watched the cattle trundle along the road past his house.

There was a faded photograph of Lizzie at Rhyll Jetty with two men and two women dressed in early twentieth century garb, the women each in long full skirt, hat and gloves, the men wearing waistcoat, jacket and hat. The dates on the sign lined up with what I remembered from Dad’s Lizzie stories. Captain Lock’s Lizzie could have been sold after his death in 1908 and she could have ended up at Inverloch in 1910. The only thing that didn’t fit was that Captain Lock’s Lizzie was a cutter (a smallish single-masted sailboat) and ‘Our Lizzie’ was a barge.

If anyone knew the answer it would be John Jansson, Phillip Island and Western Port maritime historian. I emailed John and his reply soon arrived with Lizzie’s history and a photo of her at Rhyll Jetty, the same photo from the sign on the foreshore. The last paragraph of John Jansson’s history of Lizzie confirmed she was the same vessel etched in our family’s history:

William Richardson of Rhyll bought the Lizzie in 1910 and pulled her up on the west side of the Rhyll jetty and put new bottom planks in her. He then sold her to the Shire of Woorayl for carting gravel at Anderson Inlet and in September 1915 she sank in Screw Creek near Inverloch after an explosion on board. No attempt was made to salvage her.[3]

I knew the coastal traders were important in the early settlement of coastal Victoria, but finding that ‘Our Lizzie’ had been one of them made the ‘history’ personal. I took Dad’s Family History from my bookshelf and re-read the Lizzie stories.

Around 1910, five years before Jack Graham hired Lizzie, great-grandfather Alfred won a contract to surface the road at Tarwin Lower and leased her to transport stone from a quarry he started on his land at Townsend Bluff. Dad described how Alfred and his sons Percy, Thomas and my grandfather Jack worked the quarry and how Lizzie was used to carry the stone:

The rock was blasted out of the quarry then broken into seven to ten-centimetre (three to four inch) pieces by men wielding sledge hammers. The rock was pushed in a trolley along a small rail line along a jetty to be loaded into the ‘Lizzie’. The remains of the stone jetty and badly eroded piles are still there today.

The ‘Lizzie’ was towed by their ketch called ‘Minerva’ and as the ketch was only sail-powered it was a difficult job to tow the laden ‘Lizzie’ to Tarwin Lower on the winds and tides. The next step was to sail the ‘Minerva’ to Williamstown to have a motor installed in her. This made the job a lot safer and quicker.[4]

I looked at John Jansson’s photo of Lizzie again. I pictured Grandad and great-uncle Percy’s faces from when I was young and imagined them in their weather-beaten hats, faces smeared with dirt and sweat, clothes and work-boots ragged from the labour of breaking the rock and heaving it into Lizzie’s belly.

I went back to reading Dad’s Family History and tried to visualise my great-great-grandparents, my great-grandparents and my grandfather in the stories. I wondered what brought great-great-grandfather here in the 1870s and its relevance to the wider history of the time. I wondered if great-grandfather Alfred had known of Lizzie when she was trading to Anderson Inlet and why she was later transformed into a barge. I wondered what life was like for great-great-grandma Eleanor, great-grandma Ellen and Grandad when he was young.

Discovering Lizzie’s double-identity had finally sparked my interest in the old stories and I felt sad that I hadn’t paid more attention when I had the chance. I thought how much Dad would have enjoyed sharing his stories but now it was too late. Partly from curiosity and partly to honour my father’s memory, I decided to explore the stories and their place in the early history of Bass Coast and South Gippsland and I would ask my brother John to help me.

It’s pretty easy going until our way is blocked by a watery bog but John strides on, following the edge of the quagmire. ‘There’s water everywhere,’ I shout. ‘Maybe we should go back to the bridge and start from there.’ I hear no answer and John keeps pressing on.

I fall behind as I stop to watch a fantail flitting through the branches but soon catch up and find John standing at the edge of a bright-green swampy pond reminiscent of a scene from Tolkien. Spindly paperbarks twist through each other at the edge of the pond, tufts of lomandra grasses appear like a flotilla of little boats on the surface and a tortured eucalypt arches out of the water onto the other bank. Beyond the pond is an emerald-green meadow rimmed by young paperbarks and sprawling messmate gums.

We come to a large open area once grazed by cattle, now dotted with wattles and eucalypts protected by tree guards. Nearby is a large wire enclosure where a planted bushland is flourishing. John has helped plant these trees so is confident he knows his way to the creek from here. He picks up the pace but I keep lagging behind as I pause to relish the sounds and smells of the bush.

I spot John on the far side of a watery patch of saltmarsh and soon find myself standing on the banks of Screw Creek. The creek is lined with mangroves, prickly spear grass, shrubby glasswort and spreads of beaded samphire glowing autumnal red. The tide has not fallen low enough to expose much of the muddy banks and John says, ‘I think we’re about half way between the bridge and the mouth of the creek. Let’s cut down through the bush to the Old Rock Ford while the tide drops a bit more.’

We set off through the fragrant bush towards the Old Rock Ford, wading through knee-high swathes of bracken fern, between big old messmates thick with fibrous bark, ducking beneath tangles of clematis and brushing past sweet bursaria. We peer into the entrance of a huge wombat hole, step through a maze of mossy logs and cross a swiftly flowing stream.

As I watch the creek flowing over the Old Rock Ford, contemplating how getting from place to place was never easy for the early settlers John says, ‘We’d better head upstream to look for Lizzie before the tide starts coming back in.’

We hug the creek as best we can, skirting the mangroves, pushing through patches of paperbark scrub, leaning out and peering along the exposed muddy banks for any signs of Lizzie.

‘Could that wood be from Lizzie?’ I ask hopefully, knowing it’s unlikely.

‘Don’t think so. More like from the building site across the creek.’

‘Look at that huge plank on the other side. Looks like that’s been there a while.’

‘That’s probably from the first bridge that was blown up as a war exercise before World War 2.’

‘Right. I remember Dad writing about that. It seems a bizarre thing to do!’

We finally reach the bridge at the Inverloch-Venus Bay Road where the remains of the timber piles from the original bridge are still visible at the water’s edge. But, we have seen no sign of Lizzie.

At first, J.P. leased 52 acres (30 hectares) near Hamilton then moved on to lease 266 acres (106 hectares) near Horsham before hearing of prime land for selection in South Gippsland. J.P. must have been impressed with what he found as with an inheritance of 100 pounds in hand, he wound up his lease at Horsham and pegged out a selection just north of what is now Wares Road, Leongatha South becoming one of the first selectors in the district.

J.P. lived at the Leongatha South selection, at least for a while, as Mr. W. C. Thomas who selected land nearby, wrote that he and his father "made a track for vehicles from Leongatha South to Anderson’s Inlet at a cost of about 150 pounds, and on these tracks Mr Wain, Mr Clieve and ourselves ran a fortnightly mail to San Remo (30 miles) [48 kilometres] for the convenience of ourselves and a few settlers".[6]

On his trips down the track to Anderson Inlet on his way to San Remo, J.P. would have had a good look around the area. He would have seen promise in the picturesque location at the Inlet on the cattle route from Melbourne to Port Albert and where coastal traders were already stopping by. He probably met the Henderson Brothers, who in 1876 were the first to select land around Anderson Inlet taking up 256 acres (102 hectares) at Pound Creek. He probably also met Maher who had selected land around Mahers Landing.

It is almost certain that J.P. visited Savage whose land on Savages Hill was on the Old Tarwin Road along which settlers travelled on their way to San Remo to catch the steamer across Western Port for the coach to Melbourne. At this time there was no bridge across Screw Creek but a flat bed of sandstone rock made it possible to ford the creek at low tide. J.P. recognised the opportunity of land in a strategic position on top of the hill and in 1879, selected 20 acres (8 hectares) for livery stables where travellers could rest while waiting to cross the Old Rock Ford.

Five years later, a selector wrote of his journey by horseback from Leongatha to investigate the land around Anderson Inlet and Lower Tarwin and after being hosted at the Inlet by the postmaster, Mr Laycock he crossed the rock ford and met J.P. at his house on top of the ridge:

The road from the inlet crosses Screw Creek about a mile to the east of Laycock’s. By keeping too much to the right I was pulled up at a pretty little bay, into which this creek discharges itself, by a deep tidal channel, which is closely lined by small mangroves. [...] Following the course of the creek from the mangroves, I struck the road, or more properly, beaten track at the usual crossing. The tide was now nearly full [...] my horse partly swimming. At low water, I afterwards learned, this ford has only a few inches of water.

About two miles and a half from Laycock’s the road mounts over a higher spur of the ridge, on which is situated Mr. Wain’s selection. I called at this gentleman’s house, which is close to the road, in order to congratulate him upon the splendid prospect his house commands.[7]

In 1880, J.P. acquired yet another fine property, on what is now Bambrooks Road, Inverloch where he built a large home with views of Eagles Nest, Venus Bay and Cape Liptrap. Perhaps he bought this for Eleanor who might have preferred a residence away from the livery stables or perhaps there were already plans in the making for his daughter Ellen.

In 1835, when John Batman intruded into Port Phillip, without the authority of the Colonial Government, the only Europeans who had ventured ashore between Western Port and Cape Liptrap were sealers, whalers and various British and French explorers.

Later that same year, Samuel Anderson who had also come up from Van Diemen’s Land, sailed to Western Port where there was a thriving wattle-bark trade. With his partner George Massie and a few hired workers, Anderson established a wheat farm of about 150 acres (60 hectares), a flour mill, salt works and orchard on the banks of the Bass River.

Before long, large areas of land were being taken up as pastoral leases for cattle grazing. Anderson and Massie took up land from Old Settlement Point (Corinella) to Griffith’s Point (San Remo) in 1838, the McHaffie brothers leased the whole of Phillip Island in 1842 and the Wild Cattle Run first held by Alexander Chisholm stretched from the Powlett River to the Tarwin.

The Tarwin Run, south of Anderson Inlet and the Tarwin River, was first leased by George Raff in 1842 and swiftly passed on to Alex Hunter then Edward Hobson who used it as a resting place for stock on route to Port Albert. These men held no interest in settling on the rough scrub-covered country with its sprawling swamplands and treacherous river crossing, but George Black envisaged fine prospects for the fertile flats and took up the Tarwin Run in 1851. Black would eventually hold land from Cape Paterson to Cape Liptrap and Shallow Inlet and make ‘Tarwin Meadows’ famous for its fine clover pastures and prime beef cattle.

In the early 1840’s, graziers were also taking up land further south and in 1841 when the Gippsland Company established at Port Albert, cattlemen needed a route for moving cattle to and from Melbourne. Cutting an inland route through the heavily timbered forests of South Gippsland to Warragul was proving difficult and in April 1841, George Augustus Robinson, Victoria’s Chief Protector of Aborigines, was sent to find a suitable coastal route from Port Albert to Melbourne and to report any encounters with the ‘Aborigines’.

Robinson’s party included six armed and mounted ‘native’ policemen, their sergeant, three government men and English artist and writer, George Haydon. It was hard going driving the bullock dray through the thick scrub, creek and river crossings were difficult, sometimes dangerous, and in places the ground was so boggy that ti-tree was cut down and laid in ‘corduroy’ lines for the dray to cross.

At Anderson Inlet, Robinson’s party had to cross Screw Creek but Haydon wrote that here they were, ‘fortunate enough to find a ledge of rock which stretched across and afforded just space enough for the dray to pass over.’ [8] This ledge became the Old Rock Ford that travellers used for crossing Screw Creek before a bridge was built.

Maud Black, George Black’s daughter, was one such traveller and describes how the timing of the creek and river crossings was governed by the tides:

A trip to Melbourne was a very serious business before the bridge was built over the Tarwin and could only take place on a few days of each month as some rivers had to be crossed at high tide and others at low tide. We had to cross the Tarwin at high tide, unloading the wagonette, running it into two boats by ropes and planks and run it across using the planks and ropes to haul it onto the far bank. Then the luggage was taken across and finally the horses swum behind the boats to the far side. Load the wagonette again with luggage and passengers. The horses had a hard pull for half a mile of flat country. On reaching Screw Creek near Inverloch (Laycock’s), we crossed the creek at low tide on a sandstone bar and stayed the night at Captain Laycock’s place just below the present Pine Lodge.[9]

While the low tide crossing at Screw Creek was key to great-great-grandfather Wain’s decision to select land on Townsend Bluff it was a crucial piece of legislation that paved the way. Victoria’s Land Act of 1869 provided the opportunity for ‘ordinary folk’ to select up to 320 acres (128 hectares) of un-surveyed land. After pegging out a claim, a selector would apply for survey to the Lands Department in Melbourne and if approved, could buy the land after three years, providing he had lived on the land, built a house and fences and cleared some land for cropping.

Selection was a deliberate act to break the stranglehold of the wealthy pastoralists over large areas of land and to populate the countryside with farms, towns and communities for the development of the social and economic life of the Colony of Victoria.

The selectors arrived, often on horseback, to uncleared bush. The few rough tracks became quagmires in winter and spring, there were few if any bridges and it was clear that goods and supplies would need to be brought in by sea.

Around the same time J.P. was pegging out his selection at Leongatha South, Captain Lock’s Lizzie would have started trading to Anderson Inlet via Rhyll. The ketch Ripple became a regular visitor and the Wunthalong, Templar, Moonah and Manawate arrived from Hobsons Bay (Melbourne). The coastal traders brought provisions and materials, sometimes household furniture, a piano or organ to brighten the evenings with music and returned with sheepskins, hides, butter and other farm products.

Horses or bullocks hauled wagons, carts or drays to the Inlet from the nearby coastal plains, the foothills around Kongwak and Outtrim and from the tall timber country up in the hills. In the early 1880’s, a group of selectors around Jumbunna and Jeetho, finding the cost of cartage from Poowong too high, went to great lengths to cut a track to the Inlet. Mr. A. W. Elms described the undertaking:

Herring and I went by compass out to the plains, and, looking out for the most promising looking ridge made our way back by it. As it seemed suitable for a track, all interested worked together, and after some weeks of work, opened up a sledge track from Glews down the ridge where Outtrim now is, and out to the plains. We made a substantial bridge over the Powlett River almost exactly where the present bridge is […] After this, our goods came by schooner or ketch to Anderson’s Inlet, thence to the foot of the hills by bullock waggon, and then by sledge or pack horse to the various settler’s homes.[10]

The coastal traders were crucial to the new settlers, but it certainly wasn’t smooth sailing. For a while there was no jetty for unloading goods so they were brought ashore by rowing boat and stored in the jetty shed. Carting a laden wagon back to the hills was fraught with problems so most selectors ordered supplies from Melbourne to last them a year. Even so, the traders’ visits were so unreliable there were often fruitless trips down the rough track and back again with an empty wagon.

In January 1881, Ellen and Alfred married and moved into the Wain homestead to help operate the livery stables. Photo portraits of the couple around the time of their wedding show Alfred with a shock of black hair, full beard and moustache. Ellen’s parted hair is pulled severely off her face, her black blouse is buttoned tightly to her neck softened ever so slightly with a touch of lace, a locket and chain is pinned to her breast. Her gaze is strong and there is no smile upon her face.

As far as we know, Ellen did not keep a diary so I can only imagine what life was like for her raising a family and helping run the livery stables, where travellers might stay for an hour or two or sometimes overnight.

A first-hand account by Miss C. Elms who kept house for her brother at Moyarra, near Kongwak, in the 1890’s gives a sense of day-to-day life for women at the time:

The only means of baking was in a camp oven [...] It was hot work, lifting the oven about and shovelling the hot ashes on the lid. [...] My first butter was churned in the milk bucket with a large home-made wooden spoon. [...] We did not possess an iron tank and all the water had to be drawn up in a billy or bucket out of a waterhole swarming with the larvae of mosquitoes. […] I possessed one small tub and one flat iron for laundry purposes [...] Sometimes I would not see a woman for weeks when I was too busy to go visiting, for my time was fully occupied with housework, gardening, mending and reading.[11]

Conditions for Ellen may have been slightly better. She possibly had the luxury of a wood stove and water tank but like Miss Elms, her days were probably spent cooking meals, baking bread, milking the house cow, churning butter, growing vegetables and washing laundry under rudimentary conditions. The demands of running a household, raising the children and hosting guests would have left little leisure time. Apart from visits from her mother there would have been little or no female companionship with few other settlers nearby at the time. In summer, bushfires were an ever-present threat and in 1887, the property was completely overwhelmed by fire. On 16 March, 1887 the South Bourke and Mornington Journal reported:

Several disastrous bushfires have occurred lately in the vicinity of the Tarwin, one in particular happened at Anderson Inlet to a selector of the name Wain. He lost everything he had, only saving one or two blankets. His house and contents were entirely consumed. Great sympathy is expressed for the sufferer, as it is the second time he has been visited by the same fearful calamity.[12]

The house was rebuilt after the bushfire of 1887 and the livery stables continued to operate. While Ellen did the ‘woman’s work’, one of Alfred’s responsibilities was getting provisions for the family and guests. Alfred would have crossed the Old Rock Ford to get supplies from Laycock’s store but when the traders hadn’t arrived for a while and supplies at the store ran short, he saddled up his horse and pack horse and rode to Koonwarra.

The 28-mile (44 kilometre) return trip from the homestead and stables would have been an all-day affair. It wasn’t easy for a man to pack a three hundredweight (135 kilogram) load on his own, packing one side, propping it with a stick then moving to pack the other side with the horse shifting about. If the weather was bad or the packing had not gone smoothly, Alfred might still be on the bush-track after sundown, using a candle and bottle for a lantern to light his way in the pitch dark. Mr W. H. C. Holmes recalled the dangers and difficulties of pack tracking in those days and the care required to pack the load:

The arrangement of the pack load [...] required considerable care in arrangement to the ensure the goods arriving at their destination without foreign flavours. A careless loader might place either the sodden salt beef, kerosene, etc. on top of the load, with dire results to the flour or sugar, and many a pioneer has had to endure the flavour of kerosene in his bread or tea, for months perhaps, while ‘wading’ through a bag of flour or sugar upon which a leaking tin of kerosene had been packed.[13]

J.P. was the patriarch and revelled in playing host to the travellers and other visitors who stopped by. Later in 1887, J.P. died unexpectedly at the age of 55 and Alfred and Ellen carried on the livery stables together. The following year, Eleanor married John Wydell (also known as Tarwin Jack or Wallaby Jack) a well-known identity around the district, but she was widowed again in 1891. Eleanor was in Inverloch for the 1903 census but later returned to South Australia where she lived with her sister and brother-in-law until her death in 1914, aged 87.

Sadly, unlike her mother, Ellen would not enjoy a long life. Whether it was from the trauma of the house burning down, the loss of her father, the strain of her daily tasks or a predisposition, Ellen developed heart problems and despite being under a doctor’s supervision for some time, passed away on 17th May, 1891 at the tender age of 33. Ellen was the first person to be buried at Inverloch Cemetery and was joined one month later by her five-year old son William who died of croup.

Grandad was only two and a half years old when his mother died and along with his surviving siblings, went to live with the Graham family until his older sister Eucie, not quite twelve years of age, was considered old enough to leave school and take on the ‘mother’ role cooking and caring for the family. Alfred then involved himself in planning for a bridge over Screw Creek so his children could walk to school regardless of the tide.

I loved coming here with Dad when we were kids to ‘help’ check the cows and feed them hay. Every autumn when we were little, our dairy cows were ‘dried off’ for a ‘holiday’ from milking and Dad and my Uncle Alf would herd them from our farm further up Screw Creek and bring them across our neighbour’s property to graze on the 20 acres Grandad still owned on top of the bluff.

Grandad sold the property to Mr Henderson in the late 1960s and it has since been subdivided into four five-acre lots with homes and gardens tucked among established trees. The place is unrecognisable from the cleared paddocks with uninterrupted views over Anderson Inlet that I remember and with thick scrub along the roadside, tall eucalypts and wattles, it probably looks more like when J.P. and the family lived here. One of the places offers ‘villa’ accommodation and I can’t help smiling that J.P. was a man of vision.

I feel quite emotional standing on the hill with John, looking across the Inlet, sensing Dad here with us. I wish Kevin (who lives in Queensland) could be here to share this moment. I can see my Mum Irene, standing next to Dad, smiling and rolling her eyes that we’re going back over the old family stories. I smile too, knowing she’s happy we are here together.

A steep path leads us down the side of the bluff through tall eucalypts and paperbarks and at the bottom, half obscured by undergrowth, is a weather-beaten wagon-wheel lying on the ground. Perhaps it rolled down from the livery stables all those years ago.

We emerge onto a fringe of salt marsh, mangroves and stony mudflat a few hundred metres east of Screw Creek. It is low tide and the Inlet is an expanse of sandflats interspersed with stranded pools. In the distance between Point Smythe and the Bunurong Cliffs sits the familiar shape of Eagles Nest.

It is now 110 years since Grandad, his father and brothers quarried stone from the side of the bluff and the loading jetty is still visible as two rows of weathered timber piles, some almost half a metre high, stretching towards the water across the stony shore.

The Cuttriss quarry was a small-scale, short-term affair but it was part of much bigger changes taking place. Victoria had recently become a State of the Commonwealth of Australia and land clearance, telephone lines, railway lines, decent roads and bridges were needed to pave the way for progress.

Lizzie had given three decades of service carrying cargo to the new settlers and her transformation from trading vessel to barge for carrying stone for roads was a sign that the era of the coastal traders was in decline.

In 1910, Grandad was at the start of his working life. He had been working for wages ringbarking trees and clearing the bush around the district and cutting scrub for the telephone line around Tarwin Lower. After working the quarry and towing Lizzie to Tarwin Lower behind Minerva, he shovelled mud to help drain the Koo Wee Rup Swamp in places horses could not go. From around 1912, he and his brother Percy took up the mail run from French Island to Stony Point, Hastings and Cowes aboard Minerva. It was as if, in doing so, they restored the link between Western Port and Anderson Inlet that Lizzie had established more than three decades before.

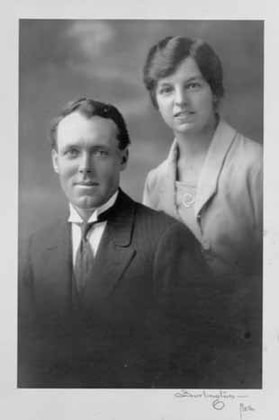

Jack and Daisy Cuttriss wedding photo c.1922

Jack and Daisy Cuttriss wedding photo c.1922 When Grandad passed away in December, 1969 he was honoured in the local newspaper. The article began:

[Mr Cuttriss] will be remembered as an intensely patriotic man, ever ready to help in the improvement of the community. Born 81 years ago into a family which pioneered the Inverloch district, he lived on a farm in the vicinity of the present Cuttriss Street. As a young working man, Mr Cuttriss ferried blue stone from the quarry at Savage’s Hill for road making at Tarwin Lower. The barge “Lizzie” can still be seen in Screw Creek Inverloch.[14]

The newspaper article was a tribute to Grandad’s pioneer work, his service in World War 1 and his welfare work especially as ‘a keen collector [fundraiser] for both the Wonthaggi and Leongatha Hospitals’. I found it fascinating that after 60 years, Lizzie was such a part of local folklore that the family’s connection with Lizzie was remembered along with him.

We are not far from the footbridge that crosses Screw Creek when John points down to a small piece of geotextile membrane protruding from the edge of the path. ‘There’s an Aboriginal midden there, mainly limpets, marine shellfish so there must have been a camping place here beside the creek.’ He explains that they discovered the midden while planning the path and a cultural heritage officer showed them how to protect it by laying the membrane over the midden to stop the gravel path mixing with the sand and shells.

Steve Compton, as Coordinator of the Bunurong Land Council Aboriginal Corporation, wrote that, ‘Lowandjeri Bulluk traditional land takes in the catchment of Anderson’s Inlet, the Tarwin River and Waratah Bay; it also included Wilson’s Promontory, Cape Liptrap, the Glennies Group and the Anser Group of Islands’. He explains that in the warmer months they visited ceremonial grounds at the coast accessing seafoods, seeds, yams, orchid bulbs and bush fruits. In winter, family groups would move up to the hills to hunt kangaroo, catch small game and birds and harvest tubers and the pith from tree ferns. Here they would meet up with families from the neighbouring Yalloc Bulluk clan and together they would travel to ceremonial grounds in the mountains.[15]

The Lowandjeri Bulluk produced and traded stone axe-heads from quarries on their traditional lands and anthropologist Aldo Massola claims this afforded them good relations with their neighbours:

Stone axes were most important in Aboriginal economy, and any group having a quarry in its territory would be friendly with all its neighbours; nor could they be disposed of it by force, since the aggressors would lack the necessary “magic” for working the quarry and the stone would not make good axes.[16]

The stone quarries were at Ruttle’s Quarry a short distance north-west of Inverloch, at Pound Creek and at McCaughan’s Hill but tragically, they were later quarried for ‘road metal’ and all traces of the stone-axe industry were destroyed.

Bunurong/Boon Wurrung people were the first in Victoria to be impacted by European colonisation. Sealers were at Seal Rocks on Phillip Island from at least 1801, three decades before Melbourne was founded and the pastoralists started moving cattle onto traditional lands. Sealers stole Bunurong/Boon Wurrung women for wives and used them to help catch and skin the seals and Bunurong/Boon Wurrung men were killed in the conflicts that took place. The surviving family members were bereft and the social and economic fabric of traditional life was shattered.

On the 1844 expedition through the Tarwin area with Robinson, George Haydon wrote that he did not meet any ‘Aborigines’ but he noticed the trunks of many trees near the Tarwin River had been stripped of bark for making canoes and found a deserted camp of over 100 huts. When George Black arrived at Tarwin in 1851 there were only six ‘aborigines’ there but it is unclear whether they were Lowandjeri Bulluk or members of the neighbouring Gunai Kurnai tribe.[17]

Steve Compton’s account of how the Lowandjeri Bulluk succumbed and finally left their lands is heart-breaking:

The Lowandjeri had for millennia, maintained amicable relationship with the Gurnai from East Gippsland through trade, ceremony and a balanced population to defend their customary and hereditary rights. The impacts of the early sealers and whalers on the Lowandjeri Bulluk population through abductions and murder was devastating and by the 1830’s the Lowandjeri Bulluk were unable to defend themselves against the Gurnai’s superior numbers. By the 1840’s, the last few surviving families of the Lowandjeri Bulluk made their way to Melbourne to be among the other Koolin tribes assembled there.[18]

As far as I knew, there were no Aboriginal people at school when I was growing up at Inverloch. The history books were silent about how Aboriginal people disappeared from their lands and of families torn apart, stolen children, denial of language and culture and no human rights. I am still conflicted about feeling pride in my pioneer family history while knowing of the loss and suffering of the First People. I am thankful that some things are slowly changing for the better. Bunurong/Boon Wurrung and other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are coming to live in Bass Coast and South Gippsland. First Nations People are voicing their stories and a more truthful, two-way history is emerging. It is important to hear these stories, learn from them, respect and appreciate First Nations culture, knowledge, world-view and walk side by side in this land.

Screw Creek is now an oasis of bushland at the edge of a busy coastal town, a peaceful refuge that belies the harsh extremes of the early European history of the area. The devastation wrought upon the Bunurong/Boon Wurrung, the rough cutting down of the bush, the breaking of stone, the violence of Lizzie’s demise.

Behind the old stories are people born into a time and place. J.P. was a man of ambition, in a land of opportunity. Alfred played ‘second fiddle’ to his patriarchal father-in-law but he did what he had to do. Ellen’s busy days were probably tinged with loneliness and uncertainty and her life was cut tragically short. Grandad lost his mother so young and his working life was hard and rough but perhaps this shaped his ‘pioneer spirit’ and spurred him to strive for a better world for his family and community.

As we follow the path through a tunnel of coast tea-tree and pass the sign to Townsend Bluff where a once-bare hill is now a haven for birdlife and wildlife, I am reminded that the push for progress and development at the heart of the old stories is by no means confined to history. If not for an army of local volunteers, Screw Creek would now be lined with houses and the bush would be gone.

We reach the footbridge where Screw Creek curves by lush mangroves and flows out to the Inlet. Standing here now, I can see my great-great-grandparents and great-grandparents and know my grandfather in a warm new light. I can picture the rough tracks, creek and river crossings, the cattle and horse-drawn wagons moving through the landscape. I can hear echoes of the Lowandjeri Bulluk stone-axe makers and see their middens all along the coast. Visiting the places in the old stories with my brother, sharing our discoveries and reliving cherished memories from childhood has been like a long-awaited homecoming. My search has been for my father, to honour his Family History and I have felt his presence with me as we walked the old pathways together.

Unpublished documents

- Len Cuttriss, History of the Cuttriss Family and their connection to the development of Inverloch and District, 2000

- John Jansson, ‘Cutter Lizzie’, undated

- Gill Heal, Tales from the Inlet, script for a theatrical production performed at Inverloch, 2009

- Morna Kenworthy, Our Family Wain and Cuttriss, 2016

- Lis Williams, George Haydon’s journal of his journey overland from Westernport to Alberton with George Robinson in April, 1844, unpublished notes on Haydon’s journal, 2001

Published sources

- Australian Heritage Group, South Gippsland Heritage Study Vol 1. Thematic Environmental History, (Reviewed by David Helms 2004), South Gippsland Shire, 1998

- Bronwyn Teasedale, ‘Screw Creek - a Brief History’, South Gippsland Conservation Society Newsletter, South Gippsland Conservation Society, 16/5/2020

- Rod Charles and Jack Loney, Not enough grass to feed a single bullock: A History of Tarwin Lower, Venus Bay and Waratah, Rod Charles, 1989 (Originally published as J.R. Charles, A History of Tarwin Lower 1798-1974, Tarwin Lower School Committee, 1974)

- Government of Victoria, Bunurong Marine and Coastal Park: Proposed Management Plan, Department of Conservation, Melbourne, 1992

- W.R. Hayes, The Golden Coast: History of the Bunurong, South Gippsland Conservation Society, Inverloch, 1998

- Thomas Horton and Kenneth Morris, The Andersons of Western Port by, Bass Valley Historical Society, Bass, 1983

- Aldo Massola, ‘Notes on the Aborigines of the Wonthaggi District’, Victorian Naturalist, Vol. 91, Feb 1974, pp. 45-50

- Screw Creek Management Plan (revised), South Gippsland Conservation Society, 2020

- South Gippsland Development League, Land of the Lyrebird: A Story of the Early Settlement in the Great Forest of South Gippsland, Shire of Korumburra, 1966 (First published by Gotch and Gotch (Australasia) Limited for the Committee of the South Gippsland Pioneers Association, 1920)

- Lis Williams, Shifting Sands Inverloch - a Fascinating Place, South Gippsland Conservation Society, Inverloch, 2002

Newspapers

- Age (Melbourne), ‘Shipping Intelligence’, 10 January 1887, 5 May 1888, 3 December 1909, 25 January 1910, 20 April 1911

- Argus (Melbourne), ‘Sea v Rail’, 19 February 1903 p. 6

- Australasian (Melbourne), ‘In the Great Forest of South Gipps Land - To Anderson’s Inlet and the Lower Tarwin’ by Selector, 15 November 1884; ‘To the Editor of the Australasian’, 16 June 1894;

- ‘Tarwin Meadows. Owned by Mr. G. Murray Black is a Monument to Courage’ by R. W. E. Wilmot 26 April, 1941

- Great Southern Star (Leongatha), ‘Woorayl Shire Council, Monthly Meeting Notes’, 28 September 1915

- South Bourke and Mornington Journal (Richmond), ‘Tarwin River’, 16 March 1887

- The Star (Leongatha), ‘In’loch pioneer passes’, 23 December 1969

Websites

- Australian Bureau of Statistics Land Tenure and Settlement

- https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/featurearticlesbytitle/88FD067140FC3F4DCA2569E300102388?OpenDocument accessed 2 July 2020

- Steve Compton, ‘The Bunurong People’, Inverloch Historical Society, 2016-2020 http://inverlochhistory.com/the-bunurong-people/ accessed 14 June 2020

- Neil Gunson, ‘Anderson, Samuel’ in Australian Dictionary of Biography http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/anderson-samuel-1706 accessed 29 June 2020

- Inverloch Cemetery Trust, Inverloch Pioneer Cemetery: Burials http://www.inverlochcemetery.org/pioneer%20burials1.htm accessed 31 August 2020

- Wikipedia, ‘San Remo, Victoria’ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Remo,_Victoria, accessed 29 June 2020

Acknowledgements

Thanks to my brother John Cuttriss for maps and photos, for guiding me through the places at Screw Creek and for some of the details behind the stories. Thanks to Sophie Cuttriss for finding Lis Williams notes. Thanks to cousin Morna (Eucie’s granddaughter) for your family research and for writing Our Family Wain and Cuttriss for Dad. Thanks to my wonderful father, Len for writing the History of the Cuttriss Family and their connection to the development of Inverloch and District for his family to know and understand our roots. And thanks always to my darling mother, Irene.

[1] Great Southern Star (Leongatha), ‘Woorayl Shire Council, Monthly Meeting Notes’, 28 September 1915, p.2

[2] Australasian (Melbourne), ‘To the Editor of the Australasian’, 16 June 1894, p. 25

[3] John Jansson, ‘Cutter Lizzie’, undated

[4]Len Cuttriss, History of the Cuttriss Family and their connection to the development of Inverloch and District, 2000

[5] Bronwyn Teasedale, ‘Screw Creek - a Brief History’, South Gippsland Conservation Society Newsletter, 16/5/2020

[6] South Gippsland Development League, Land of the Lyrebird: A Story of the Early Settlement in the Great Forest of South Gippsland, Shire of Korumburra, 1966, p. 203

[7] Australasian (Melbourne), ‘In the Great Forest of South Gipps Land - To Anderson’s Inlet and the Lower Tarwin’ by Selector, 15 November 1884, p.10

[8] Lis Williams, George Haydon’s journal of his journey overland from Westernport to Alberton with George Robinson in April, 1844, unpublished notes on Haydon’s journal, 2001

[9] Rod Charles and Jack Loney, Not enough grass to feed a single bullock: A History of Tarwin Lower, Venus Bay and Waratah, Rod Charles, 1989, p. 34

[10] South Gippsland Development League, Land of the Lyrebird: A Story of the Early Settlement in the Great Forest of South Gippsland, Shire of Korumburra, 1966, p. 264

[11] South Gippsland Development League, Land of the Lyrebird: A Story of the Early Settlement in the Great Forest of South Gippsland, Shire of Korumburra, 1966, pp. 368-9

[12] South Bourke and Mornington Journal (Richmond), ‘Tarwin River’, 16 March 1887

[13] South Gippsland Development League, Land of the Lyrebird: A Story of the Early Settlement in the Great Forest of South Gippsland, Shire of Korumburra, 1966, pp. 45-6

[14] The Star (Leongatha), ‘In’loch pioneer passes’, 23 December 1969

[15] Steve Compton, ‘The Bunurong People’, Inverloch Historical Society, 2016-2020 http://inverlochhistory.com/the-bunurong-people/ accessed 14 June 2020

[16] Aldo Massola, ‘Notes on the Aborigines of the Wonthaggi District’, Victorian Naturalist, Vol. 91, Feb 1974, p. 49

[17] Ibid p.46-8

[18] Steve Compton, ‘The Bunurong People’, Inverloch Historical Society, 2016-2020 http://inverlochhistory.com/the-bunurong-people/ accessed 14 June 2020