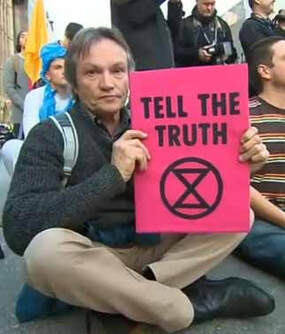

Neil Rankine shortly before his arrest on a charge of obstructing emergency services. Image: Channel 9

Neil Rankine shortly before his arrest on a charge of obstructing emergency services. Image: Channel 9 NEIL Rankine doesn’t fit the stereotype of a climate change activist, by Channel Nine’s reckoning. He is too old and too respectable. “Sixty-two years old, a former mayor, long-time councillor and for decades a CFA volunteer,” reporter Brett Mcleod noted. “But Neil felt so strongly about this issue that he was prepared to be arrested and for the first time in his life locked up overnight.”

On October 7, Mr Rankine, a former Bass Coast mayor, was charged with three counts of obstructing an emergency worker during an Xtinction Rebellion (XR) sit-in near the Flinders Street Station. Holding up a hand-made sign reading “Tell the truth”, he was the first protestor to be arrested during a week of protest action in the CBD.

Despite his evident tiredness, he stayed on message. After all, commercial TV doesn’t usually show much interest in climate change. “We have to stand up,” he told the reporter. “We have to take a stand. I’ve attempted all sorts of other ways to get things happening.”

But it would be a mistake to regard him as a regular bloke. He is a scientist, a thinker, a questioner, an unlikely politician and a reluctant activist.

He spent the day before his arrest at home, on a small rural property just outside Wonthaggi. He and his five-year-old grandson, Sam, were building a cubby house in a tree. When they finished the platform they sat there watching the birds and trees and clouds. In the midst of the natural beauty, he felt an immense sense of impending loss. How much of this would be left when Sam was his age? In 50 years, how would humans be living? How many species would have disappeared from the earth? Would the earth even be habitable?

As a scientist and reader, Neil first heard of climate change more than three decades ago. At first he thought the dire predictions were a little far-fetched, but the more he read and learned the more he was convinced. Over the past decade he has read and listened to the evidence with a growing sense of dread.

“The IPCC are telling us that if we don't get to zero net emissions in 10 or 12 years we sail past our agreed Paris target of 1.5 degrees and most corals are dead. Next comes 2 degrees where all corals are dead and we've lost hope or technology of safely controlling the situation.”

Ask any farmer in Queensland and NSW, he says. They know about climate change. We might have a bit more breathing space in South Gippsland but in time this region too will be ravaged by drought and bushfire and flooding, just like the rest of Australia.

So why do the politicians go on playing political games while we hurtle towards oblivion? After all, they’re parents and grandparents too.

“It’s a tough one,” Neil replies. “I’m sure they care about their children’s future too. They must have mechanisms in their brain that are telling them that everything is going to be okay.”

In the cubby with his grandson that day, he thought “I’m not backing down. This time I’m making a stand.”

Channel 9 reports on the arrest

Channel 9 reports on the arrest Later they caught up with the main XR group. It was a rapidly moving protest, travelling from intersection to intersection. The idea was to block one side of the intersection for a few light cycles, before moving on and doing it somewhere else, so no one was ever massively inconvenienced.

Near the Flinders Street Station, the police had already blocked off the intersection with a ring of officers on horseback. Neil decided this is where he would make his stand, or rather sit tight. After a couple of warnings, he became the first protestor to be arrested. The police carried him to the police truck and took him to the West Melbourne police cells, where he declined several times to accept the bail conditions.

He spent the night in the remand centre and appeared the next morning in the Melbourne Magistrates Court. Despite the discomfort, it was worth holding out, because the magistrate simply bailed him to appear in court in Wonthaggi in November, without conditions.

In 2007, his life was changed forever when the State Government announced it was going to build a massive desalination plant on a coastal plain near Kilcunda. At first, like most Victorians, he thought “I suppose they know what they’re doing.” Then, in his usual way, he started reading scientific papers about desalination. Opponents call it “liquid electricity” because it’s the most energy-intensive way to produce water. Then there is the by-kill of krill and other marine organisms that are vital to the food chain.

He joined the local action group, Your Water Your Say. He read the data and spoke to the experts. He factored in the CSIRO's worst case for climate change and the expected population increase in Melbourne. And he concluded that the desal plant was an energy-consuming, expensive waste that would massively increase the cost for Melbourne water users and shut out more sustainable options such as using stormwater.

Professor Barry Hart, chair of the Water Studies Centre at Monash University, endorsed his independent study and it was widely reported. The State Government never refuted his conclusion; it just ignored them and the $3 billion plant was built, despite a concerted local campaign against it.

Desal protestors stand firm, 2008. Neil Rankine is on the left.

Desal protestors stand firm, 2008. Neil Rankine is on the left. Around this time he joined the Greens Party and helped to write their water policy. In early 2010 they asked him to be the candidate for Bass in the state election. “Forget it,” he said, but added “If you get desperate, give me a call”. A month later he got the call he’d been dreading. They couldn’t find another suitable candidate.

Although he took it on reluctantly he gave it everything he had. For eight months he put in virtually 14 hours a day campaigning. “Anything I do I do pretty hard. I suppose I do get obsessive about things.” He lifted the Greens vote by about 20 per cent but was also reminded that he wasn’t cut out for political life. “A good politician has to be able to get out there and chat to people and shake hands and be involved in the footy club and it’s just not me.”

Which is why those who knew him were surprised when he stood for election to the Bass Coast Council in 2012. Like many candidates that year he was spurred on by the appearance of a political party known as the Reform Team, founded by former Liberal MP Alan Brown, which stood candidates in every ward. Neil defeated Mr Brown in the Wonthaggi ward and took his place on the council. In his first year his colleagues elected him deputy mayor of Bass Coast. The following year he became the mayor, an unlikely gig for a man who, by his own admission, lacks the silver tongue that makes a good politician.

In Channel 9’s coverage of Neil’s arrest, they played archival footage of the former mayor addressing a large crowd in Cowes in 2014, at the height of the Stand Alone movement. Phillip Island wants a divorce from Bass Coast. As Neil enters the Cowes Cultural Centre, the loudspeaker is blaring the rallying song from Les Miserables. “Do you hear the people sing?” it starts, “Singing a song of angry men.”

The mayor takes the microphone and tries to explain that splitting from Bass Coast will increase costs for island ratepayers. There is heckling and jeering from the hostile crowd. “Okay, so rational argument might not work,” he says affably. The situation is so dire that he actually smiles. Predictably, the crowd bays but I think of it as Neil’s finest political moment.

Neil lost his second tilt at the council in 2016. It hurt him because he felt he was defeated by misinformation. It was also entirely predictable. Reasoning is his strong point and it was not an age of reason in Bass Coast. The mob held sway, backed by the local newspapers which published outrageous claims as fact.

In an interview in 2017, current Bass Coast Mayor Brett Tessari told the Post. “I was one of those that was critical of the previous council. Now that I’m on the inside, I can see they made a lot of hard calls, and copped a lot of flak for it, but the shire is now reaping the benefits. So belated credit to them for that.”

Cr Michael Whelan, however, paid tribute. “I want to acknowledge our former mayor Neil Rankine who put his hand up last week and was one of those arrested in Melbourne. Power to him …”

Cr Geoff Ellis, a friend of Neil’s and fellow car buff, says of his arrest: “He's braver than me. I would have moved on, obeyed and run home to write a piece for The Post.

“Neil doesn't have the politician gene in his DNA. The rest of us have this need to be seen, to be noticed. The hand extended for a hearty shake is a reflex action that doesn't come naturally to him.

“You know, if I don't speak to a dozen people a day I feel impoverished, malnourished. Neil would be relieved, able to spend that day in shed, head under the bonnet of a century-old French car, adjusting the carburettor.”

Now he’s got his workshop back in order and the world is calling. He owes it to Sam and all the other children who will inherit the earth. We could solve climate change, he says, if only we had the political will. Look at the massive mobilisation of the Second World War. If we decided to tackle climate change that way, it would be a huge economic boost. But most people don’t think like that.

It was an XR forum in Inverloch a couple of weeks ago that determined him. “They were talking about tipping points. If 3 or 3.5 per cent of the population gets on board with an issue to the extent that they do something out of their comfort zone, like blocking traffic, then governments take notice.”

He’s spent half his life talking about this stuff, he says, and no one’s listening any more. Now it’s time for action.