After half a lifetime of silence, Adam Cope has an extraordinary story to tell.

By Catherine Watson

April 12, 2014

WORDS are everything to Adam Cope. In Life, his new book of autobiographical poems, he writes:

“I could feel them

See them

Smell them

Beautiful words.”

The only thing he couldn’t do was say them. Cope will never talk, and can write only with difficulty (his father Les or another helper holds his arm steady so he can concentrate on hitting the right letter on the keyboard with his finger), but after half a lifetime of silence he embraces that difficulty and the words pour out.

Life is his second collection of poetry. He wrote the 66 poems to celebrate his mother Peta’s 66th birthday. It’s his autobiography, but Peta and Les are ever-present. Much of it is derived from their memories.

The poems are sparse. When every word you write is a physical challenge, there’s a lot to be said for short, simple words. And these are the most striking poems.

In Terror, he writes of his mother after his first major seizure, driving:

“with her bundle of joy

hope and terror

Hospital bound

Hope

Hope

Terror.”

At three months, Cope was diagnosed with tuberous sclerosis complex, a genetic disorder that results in severe cognitive and physical difficulties. When his parents tried to get early intervention for him, the specialist said, “Why bother? He’s severely retarded. He’s not going to live past his teens. Just take him home and love him.”

Cope went to a special school that concentrated on life skills and, just as the specialist had warned, he never uttered a word, verbally or in writing. But his rich internal world was far from a blank slate. In the depths of despair, unable to communicate with those who loved him, or even to let them know how much he understood, he made his own friend and called her Jill:

“She keeps

me sane

I talk to her

She talks back

She talks

I talk

And all is quiet.”

Later, he watched others live, while he was cocooned in his special school,

“Seeing little

of the world

Except through

a bus window”.

The first 25 or 30 poems are dark as he describes his condition and its effect on the family, but there are moments of joy and solace: in family life, in the outdoors and in camping trips to Wilsons Prom where he floats weightless in the sea.

Then there’s the day a music teacher came to the house to teach him to play a few notes. The notes on the piano related to the notes on a page, she told him.

“He hit the right notes

Margaret called out.

Mum exclaimed

With a shout

If he can read notes

He can read words.”

And so she began to try to teach him simple words, using flash cards and children’s books.

The real breakthrough came in his last year of primary school when Peta and Les took him to see Rosemary Crossley, the controversial “facilitated communication” expert who famously championed the cause of Annie McDonald, a young woman who could not speak either.

“Everyone kept telling us to take him to Rosemary,” Les says. “It took us a while to get there because we thought she’s just another expert who’ll tell us there’s nothing we can do.

“So we took him to Rosemary. She was the first person who said to Adam, ‘Do you mind if I talk about you with your mum and dad?’

“Then she started talking with him on the keyboard. His concentration was so intense, the rest of his body just went haywire. He then tapped out ‘I read’.

“Within half an hour, he was communicating with her. She asked him what he wanted for lunch. He typed out ‘pasta’.”

Cope tells the story in Talk:

“With a steady firm hand

Rosie prepared my

body

mind

and faith

Reaching out as I

Armed my mind

And soul to strike the key

Rosie kept her nerve.

Ready now

I struck

The letter cried

Success

And talk began.”

The visit changed all their lives. “We all walked out of there 10 feet tall,” Peta says. “Suddenly Adam seemed a lot older. Once he was communicating, that changed everything. We asked his opinion. We could consult him on his own life.”

One of the first things she discovered was that, while she had been trying to teach him to read using flash cards and children’s books, he had taught himself to read years before from the posters on the wall of his special school. As his communication improved, Cope’s world expanded. He left the ghetto of special education and joined a mainstream class in the local college.

The dismissive modern phrase “Same same” acquires a quite different meaning in Cheryl, his poem about an inspirational teacher who incorporated him into her class in a mainstream school and who wrote the foreword for Life.

“Lured into

Cheryl’s class

Belonging

Same

Same

Same.”

It took him four years but Cope passed his VCE. In his 30s, he left home and moved to Venus Bay, where he is now supported by a team of carers, supplemented by friends and family. When the federal government was considering a national disability insurance scheme, he and Les went to Canberra to present a paper to the Productivity Commission. A few years ago, he joined the Bass Coast Writers Group and his horizons opened even further.

The later poems in Life are happier ones, and less vivid than the earlier ones, as if Cope has spent himself in the deeply felt and heart-wrenching earlier poems. But the book concludes masterfully with the 66th poem, Warmth, in which he refers back to Jill, the imaginary friend of his lonely childhood:

“Time waiting

Quiet as Jill was

Years ago

Quiet

Winking at life

Through a place

Long gone.”

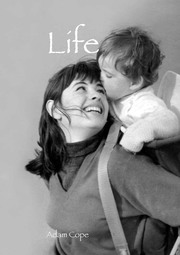

Designed by Les, a graphic designer, Life is a very classy production, from the elegant typography and layout to the beautiful cover photo of Peta and Adam. It's on sale at adam.org.au/books.

COMMENTS

April 14, 2014

I thought you may be interested in your review and article in the Post. It has gone around the world already. Adam and I are part of a number of groups involved in disability. It has been shared through social media in the States and England. Everyone is very moved by your article and Adams words.

The world is its stage. Thank you.

Les Cope

April 12, 2014

WORDS are everything to Adam Cope. In Life, his new book of autobiographical poems, he writes:

“I could feel them

See them

Smell them

Beautiful words.”

The only thing he couldn’t do was say them. Cope will never talk, and can write only with difficulty (his father Les or another helper holds his arm steady so he can concentrate on hitting the right letter on the keyboard with his finger), but after half a lifetime of silence he embraces that difficulty and the words pour out.

Life is his second collection of poetry. He wrote the 66 poems to celebrate his mother Peta’s 66th birthday. It’s his autobiography, but Peta and Les are ever-present. Much of it is derived from their memories.

The poems are sparse. When every word you write is a physical challenge, there’s a lot to be said for short, simple words. And these are the most striking poems.

In Terror, he writes of his mother after his first major seizure, driving:

“with her bundle of joy

hope and terror

Hospital bound

Hope

Hope

Terror.”

At three months, Cope was diagnosed with tuberous sclerosis complex, a genetic disorder that results in severe cognitive and physical difficulties. When his parents tried to get early intervention for him, the specialist said, “Why bother? He’s severely retarded. He’s not going to live past his teens. Just take him home and love him.”

Cope went to a special school that concentrated on life skills and, just as the specialist had warned, he never uttered a word, verbally or in writing. But his rich internal world was far from a blank slate. In the depths of despair, unable to communicate with those who loved him, or even to let them know how much he understood, he made his own friend and called her Jill:

“She keeps

me sane

I talk to her

She talks back

She talks

I talk

And all is quiet.”

Later, he watched others live, while he was cocooned in his special school,

“Seeing little

of the world

Except through

a bus window”.

The first 25 or 30 poems are dark as he describes his condition and its effect on the family, but there are moments of joy and solace: in family life, in the outdoors and in camping trips to Wilsons Prom where he floats weightless in the sea.

Then there’s the day a music teacher came to the house to teach him to play a few notes. The notes on the piano related to the notes on a page, she told him.

“He hit the right notes

Margaret called out.

Mum exclaimed

With a shout

If he can read notes

He can read words.”

And so she began to try to teach him simple words, using flash cards and children’s books.

The real breakthrough came in his last year of primary school when Peta and Les took him to see Rosemary Crossley, the controversial “facilitated communication” expert who famously championed the cause of Annie McDonald, a young woman who could not speak either.

“Everyone kept telling us to take him to Rosemary,” Les says. “It took us a while to get there because we thought she’s just another expert who’ll tell us there’s nothing we can do.

“So we took him to Rosemary. She was the first person who said to Adam, ‘Do you mind if I talk about you with your mum and dad?’

“Then she started talking with him on the keyboard. His concentration was so intense, the rest of his body just went haywire. He then tapped out ‘I read’.

“Within half an hour, he was communicating with her. She asked him what he wanted for lunch. He typed out ‘pasta’.”

Cope tells the story in Talk:

“With a steady firm hand

Rosie prepared my

body

mind

and faith

Reaching out as I

Armed my mind

And soul to strike the key

Rosie kept her nerve.

Ready now

I struck

The letter cried

Success

And talk began.”

The visit changed all their lives. “We all walked out of there 10 feet tall,” Peta says. “Suddenly Adam seemed a lot older. Once he was communicating, that changed everything. We asked his opinion. We could consult him on his own life.”

One of the first things she discovered was that, while she had been trying to teach him to read using flash cards and children’s books, he had taught himself to read years before from the posters on the wall of his special school. As his communication improved, Cope’s world expanded. He left the ghetto of special education and joined a mainstream class in the local college.

The dismissive modern phrase “Same same” acquires a quite different meaning in Cheryl, his poem about an inspirational teacher who incorporated him into her class in a mainstream school and who wrote the foreword for Life.

“Lured into

Cheryl’s class

Belonging

Same

Same

Same.”

It took him four years but Cope passed his VCE. In his 30s, he left home and moved to Venus Bay, where he is now supported by a team of carers, supplemented by friends and family. When the federal government was considering a national disability insurance scheme, he and Les went to Canberra to present a paper to the Productivity Commission. A few years ago, he joined the Bass Coast Writers Group and his horizons opened even further.

The later poems in Life are happier ones, and less vivid than the earlier ones, as if Cope has spent himself in the deeply felt and heart-wrenching earlier poems. But the book concludes masterfully with the 66th poem, Warmth, in which he refers back to Jill, the imaginary friend of his lonely childhood:

“Time waiting

Quiet as Jill was

Years ago

Quiet

Winking at life

Through a place

Long gone.”

Designed by Les, a graphic designer, Life is a very classy production, from the elegant typography and layout to the beautiful cover photo of Peta and Adam. It's on sale at adam.org.au/books.

COMMENTS

April 14, 2014

I thought you may be interested in your review and article in the Post. It has gone around the world already. Adam and I are part of a number of groups involved in disability. It has been shared through social media in the States and England. Everyone is very moved by your article and Adams words.

The world is its stage. Thank you.

Les Cope