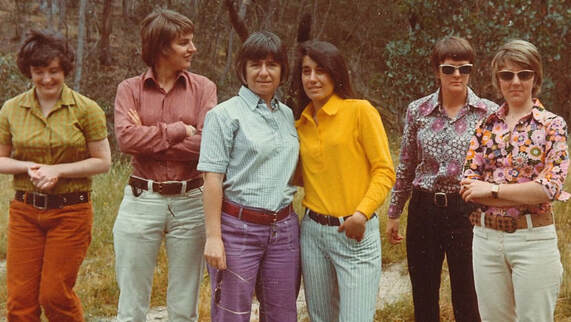

Francesca Curtis in 2015: “I have nothing to be

Francesca Curtis in 2015: “I have nothing to beashamed of …” Photo: Gary Jaynes

By Catherine Watson

Francesca Curtis was buried on the hill in the beautiful Phillip Island cemetery, in the midst of a spectacular electrical storm that seemed apt to mark the life of a fearless freedom fighter.

In Australia in 1970, male “homosexual acts” were still illegal. There was no statute against lesbianism but it was a source of great shame. Gays and lesbians were publicly vilified and often privately bashed, including by the cops. You could be fired for being queer. (You can still be fired today but now only by people of faith!) Not surprisingly, most gays kept their inner lives well hidden.

Not Francesca. In June 1970, she was interviewed about her lesbian life on a current affairs show The Bailey File. Gays and lesbians had appeared on television before but the practice was to black out their faces. Francesca declined to be hidden, thereby becoming the first lesbian to come out on Australian TV.

Francesca Curtis was buried on the hill in the beautiful Phillip Island cemetery, in the midst of a spectacular electrical storm that seemed apt to mark the life of a fearless freedom fighter.

In Australia in 1970, male “homosexual acts” were still illegal. There was no statute against lesbianism but it was a source of great shame. Gays and lesbians were publicly vilified and often privately bashed, including by the cops. You could be fired for being queer. (You can still be fired today but now only by people of faith!) Not surprisingly, most gays kept their inner lives well hidden.

Not Francesca. In June 1970, she was interviewed about her lesbian life on a current affairs show The Bailey File. Gays and lesbians had appeared on television before but the practice was to black out their faces. Francesca declined to be hidden, thereby becoming the first lesbian to come out on Australian TV.

“Why have you agreed to be interviewed full face on The Bailey File tonight?” the interviewer asked her towards the end of the interview, a note of incredulity in his voice.

Francesca replied: “I have nothing to hide, I have nothing to be ashamed of, so I decided that I would like to come on and do this full face and talk about the aims of our group.”

At Francesca’s funeral, Gary Jaynes from the Australian Queer Archives spoke of her courage: “Francesca’s decision to do the Bailey File interview strikes me as remarkably brave, especially given the few supports that were available then. The concept of Gay Pride hadn’t really been articulated then – at least not in Australia. But Francesca’s motivation for doing the interview exemplified it.”

Francesca Curtis grew up in Tarwin Lower – “like a happy little savage” as she later described herself – and later in the far more staid country town of Leongatha where she was increasingly aware that she was not like the other girls.

She escaped to Melbourne as soon as she could, eager to live a more bohemian life. Having found her tribe, thanks to a gay male friend, she determined to live her life openly. In 1969, she became a founding member of the Daughters of Bilitis, set up “to improve the lot of the female homosexual” and now considered Australia's first gay rights group.

Watching Francesca on The Bailey File that night was Phyllis Papps, the daughter of a Greek immigrant family who was engaged to be married but increasingly confused about her feelings. It was only when she saw Francesca that she started to understand. Like scores of other women, she wrote to the Daughters of Bilitis at the post box number helpfully provided at the end of the show.

A few weeks later she met Francesca, and the connection between them was immediate. And so began a loving relationship that lasted 51 years until Francesca’s death in Cowes on Christmas Eve at the age of 90.

Francesca replied: “I have nothing to hide, I have nothing to be ashamed of, so I decided that I would like to come on and do this full face and talk about the aims of our group.”

At Francesca’s funeral, Gary Jaynes from the Australian Queer Archives spoke of her courage: “Francesca’s decision to do the Bailey File interview strikes me as remarkably brave, especially given the few supports that were available then. The concept of Gay Pride hadn’t really been articulated then – at least not in Australia. But Francesca’s motivation for doing the interview exemplified it.”

Francesca Curtis grew up in Tarwin Lower – “like a happy little savage” as she later described herself – and later in the far more staid country town of Leongatha where she was increasingly aware that she was not like the other girls.

She escaped to Melbourne as soon as she could, eager to live a more bohemian life. Having found her tribe, thanks to a gay male friend, she determined to live her life openly. In 1969, she became a founding member of the Daughters of Bilitis, set up “to improve the lot of the female homosexual” and now considered Australia's first gay rights group.

Watching Francesca on The Bailey File that night was Phyllis Papps, the daughter of a Greek immigrant family who was engaged to be married but increasingly confused about her feelings. It was only when she saw Francesca that she started to understand. Like scores of other women, she wrote to the Daughters of Bilitis at the post box number helpfully provided at the end of the show.

A few weeks later she met Francesca, and the connection between them was immediate. And so began a loving relationship that lasted 51 years until Francesca’s death in Cowes on Christmas Eve at the age of 90.

Soon after their first meeting, Phyllis joined Francesca in the TV studio – again full face – to be grilled by This Day Tonight, the country’s best known current affairs show, about their lives as a lesbian couple.

Phyllis later wrote: “The program brought with it a flurry of complaints from shocked viewers. Those who weren’t complaining were the women who contacted us after the program.”

Phyllis later wrote: “The program brought with it a flurry of complaints from shocked viewers. Those who weren’t complaining were the women who contacted us after the program.”

| There was much more to Francesca’s and Phyllis’s lives than those few tumultuous years as the public face of the Australasian Lesbian Movement (the successor to the Daughters of Bilitis). Both had fulfilling careers and contributed to community and public life, including on Phillip Island where they retired in 2001. Francesca was a creative writer, an Italophile, a connoisseur of fine malt whiskies and good conversation, and lover of all things UFO. But it was her act of defiance in the face of societal prejudice and injustice that still transfixes the queer community. She was cut from the same cloth as Rosa Parks, who in 1955 galvanised the black civil rights movement when she was arrested for refusing to give up her bus seat for a white man. Or Charles Perkins, who took the fight for Aboriginal rights deep into rural Australia. It is a rare kind of courage that isn’t cowed by authority or the mob. Phyllis sometimes complained that she and Francesca had spent 50 years coming out but more recent “coming out” events were joyful ones. In 2017 they celebrated along with many millions as Australians overwhelmingly supported marriage equality. Having fought so hard for the change, Francesca and Phyllis didn’t bother getting married. In their own minds that had happened on July 11, 1970, a month after they met, when they exchanged gold wedding rings. | From Swimming With Black Swans By Francesca Curtis One morning when the tide was in and it was possible to swim, I went to the beach very early to escape the promised heat. It was already in the high twenties and I quickly plunged into the cool water. It was then that I noticed almost thirty black swans floating gracefully in my direction. I think that they were quite perturbed to see this large, clumsy creature invading their territory. They must have discussed the matter amongst themselves and decided to move in closer to view the alien presence. I stopped swimming and remained quite still, then started making noises to mimic their calls. However, they were not deceived but continued to approach me, only stopping at a distance acceptable to their wild state. How I wished that they would swim right up to me and we could have some method of communication. Although this did not happen, I still count this experience as an uplifting and rewarding one. Sadly, these beautiful creatures probably remember man’s past cruelties and are very wise to remain at a distance and out of harm’s way. Francesca's prose poem about Rhyll was read at her funeral service. |

For them, the marriage equality vote was always about acceptance and equality.

In 2019 they received the Lifetime Achievement Award at the LGBTI Awards in Sydney where Francesca spoke of handing over to the next generation of young queer people.

And in March last year they once again appeared on national TV in Why Did She Have to Tell the World, a film of their lives made by Abbie Pobjoy and Bonny Scott. At a Q&A session after the film’s premiere at the Nova Cinema, they were cheered by the mostly young audience.

It was to be their final coming out. Francesca’s health declined soon afterwards.

She is survived by Phyllis.

In 2019 they received the Lifetime Achievement Award at the LGBTI Awards in Sydney where Francesca spoke of handing over to the next generation of young queer people.

And in March last year they once again appeared on national TV in Why Did She Have to Tell the World, a film of their lives made by Abbie Pobjoy and Bonny Scott. At a Q&A session after the film’s premiere at the Nova Cinema, they were cheered by the mostly young audience.

It was to be their final coming out. Francesca’s health declined soon afterwards.

She is survived by Phyllis.