There are times when Patrice Mahoney feels like a lone voice in the wilderness, but that’s not going to stop her from speaking her mind, in words and images.

By Catherine Watson

RECENTLY someone asked Patrice Mahoney why she made art. The Wonthaggi artist didn’t have an answer. “It was like asking ‘Why do you breathe?’. It’s not a conscious decision. I couldn’t not make art.”

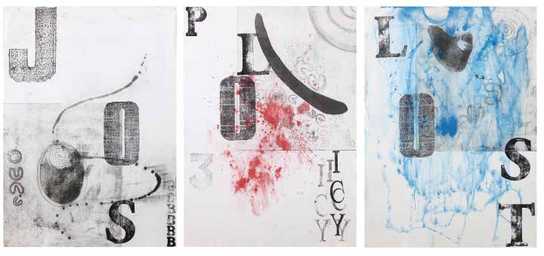

Mahoney’s artistic stocks continue to rise. Earlier this year, three of her works went on display in the First Peoples exhibition at the Bunjilaka Aboriginal Culture Centre at the Melbourne Museum. And last weekend, her triptych print Jobs, Policy and LOST won the $5000 Federation University Australia Acquisitive Award at the 2014 Victorian Indigenous Art Awards.

The judges commented: “The poignancy of connectedness to the past, memory, place and country is palpable and enhanced by the suggestive employment of text and minimal colour. A provocative and evocative work of art.”

Mahoney is particularly pleased that it’s an acquisitive award, not least because it means she didn’t have to bring the big work home from the Art Gallery of Ballarat, where the awards were announced. But she’s also pleased that her very political work will now be displayed at one of Federation University’s campuses. “I hope it will provoke debate. You have a preconceived idea that universities are places of questioning but in fact they are very conservative places.”

Patrice Mahoney with her work Jobs, Policy and LOST. Photos: Nigel Clements

Artists Paola Balla, Patrice Mahoney, Cynthia Hardie, Deanne Gilson, Jenny Crompton and Lisa Waup at the 2014 Victorian Indigenous Art Awards.

In spite of her win, she’s feeling despondent and frustrated, at least in part a reaction to the violence and conflict around the world. The hypocrisy of the mainstream commentary on the conflicts in the Middle East maddens her. “It didn’t matter when Muslims were being killed. Now Christians are being killed and suddenly it’s terrible.”

As we talk in a Wonthaggi café, Mahoney doodles on some tiny pink Post It notes. Drawing and doodling help her think. She’s always done it. If she didn’t have the Post It notes, she says, she’d be doodling on the menu. She turns her anger and frustration into art.

All this talk about political art makes her sound permanently angry but in fact she’s funny too. She’s explaining that on her Facebook page this week, she posted her thoughts on gay marriage. “Who cares what people do, if they’re not hurting anyone else?” she says. “Love a sheep if you want to. Plenty of people love their dogs. I couldn’t care less.”

She’s hoping her Christian friends will unfriend her so she won’t have to unfriend them.

She has no religion – except perhaps a belief in the brotherhood of man – and dislikes it when Christian acquaintances pray over or for her.

But back to the art. She always painted and drew as a child and has studied and made art ever since she left school. Two years ago, she completed a bachelor of visual and media arts at Monash University’s Churchill campus. Now she draws and makes prints in the kitchen and dining room, with and around her five children. “If they walk on it, they walk on it. I’m not that precious about my work.” The only concession she makes is that she doesn’t paint as much at the moment; print-making is easier when your work is subject to many interruptions.

She divides her work into two categories: more personal work, reflecting herself, her family, her place; and the political work, which she uses to express her frustration.

It often offends people, she knows, but she hopes it will at least start a conversation and create a ripple effect.

Bass Coast is not her traditional country. She is Kamilaroi, Anewan and Dunghatti from Armadale, in New South Wales. When she was 21, and wanting to get away, she closed her eyes and put her finger on a map. It landed in the sea just off Lakes Entrance so she moved there, complete with three kids and two dogs. Later she met a man whose family lived in Wonthaggi so they moved down here.

In the late 1990s, she found the place depressingly monocultural, and couldn’t see where she could fit into it. “I’d grown up in Armadale where these was a university and the community was a melting pot. Wonthaggi felt like the deep south.”

Where her son was bullied at primary school – called a “stinky Abo” – she complained to the principal, who thought it was the “stinky” she found offensive. “People here didn’t even realise ‘Abo’ was derogatory. They thought it was just short for ‘Aborigine’.”

She says there are about 200 people of Aboriginal descent in the whole Bass Coast Shire but no Aboriginal community as such. “They’re hidden.” Because of that, eventually she found herself a de facto representative of the Aborigine peoples, reminding mainstream Bass Coast society that other cultures existed before their own.

One year she persuaded the council to fly the Aboriginal flag during NAIDOC Week and someone set fire to it. Another year, she wrote to the councillors inviting them to attend NAIDOC celebrations, but neither they nor the local newspaper knew what NAIDOC was.

“They thought Sorry Day was the anniversary of Kevin Rudd’s apology to the Stolen Generations. They said they couldn’t come because they required 10 days’ notice and I’d only given them nine. I wrote back asking if they required 10 days’ notice of Christmas Day or Australia Day.”

She laughs. “For a while there I was known as ‘the lady who wrote the letter’. People used to point me out. Now when I’m angry and write something, I usually leave it till the next day to cool down and I read it through.”

She says there is always a cost to trying to live in two worlds. She is pleased to see many more non-Anglos settling in Wonthaggi, gradually opening a window into other worlds.

And she thinks her success in the art world is also reflecting on Wonthaggi. “I feel as though I’m putting Wonthaggi on the black map.”

As for me, remembering the tale of the early Picasso restaurant doodles that were worth a fortune when he became famous, I’m still kicking myself that I didn’t pick up one of the Post It notes with Mahoney’s doodles on it.

COMMENTS

September 9, 2014

Another wonderful edition ! And your article last week about Patrice told us the part of her story that has never been told. Thanks so much for your Post.

Anne Davie, Ventnor

RECENTLY someone asked Patrice Mahoney why she made art. The Wonthaggi artist didn’t have an answer. “It was like asking ‘Why do you breathe?’. It’s not a conscious decision. I couldn’t not make art.”

Mahoney’s artistic stocks continue to rise. Earlier this year, three of her works went on display in the First Peoples exhibition at the Bunjilaka Aboriginal Culture Centre at the Melbourne Museum. And last weekend, her triptych print Jobs, Policy and LOST won the $5000 Federation University Australia Acquisitive Award at the 2014 Victorian Indigenous Art Awards.

The judges commented: “The poignancy of connectedness to the past, memory, place and country is palpable and enhanced by the suggestive employment of text and minimal colour. A provocative and evocative work of art.”

Mahoney is particularly pleased that it’s an acquisitive award, not least because it means she didn’t have to bring the big work home from the Art Gallery of Ballarat, where the awards were announced. But she’s also pleased that her very political work will now be displayed at one of Federation University’s campuses. “I hope it will provoke debate. You have a preconceived idea that universities are places of questioning but in fact they are very conservative places.”

Patrice Mahoney with her work Jobs, Policy and LOST. Photos: Nigel Clements

Artists Paola Balla, Patrice Mahoney, Cynthia Hardie, Deanne Gilson, Jenny Crompton and Lisa Waup at the 2014 Victorian Indigenous Art Awards.

In spite of her win, she’s feeling despondent and frustrated, at least in part a reaction to the violence and conflict around the world. The hypocrisy of the mainstream commentary on the conflicts in the Middle East maddens her. “It didn’t matter when Muslims were being killed. Now Christians are being killed and suddenly it’s terrible.”

As we talk in a Wonthaggi café, Mahoney doodles on some tiny pink Post It notes. Drawing and doodling help her think. She’s always done it. If she didn’t have the Post It notes, she says, she’d be doodling on the menu. She turns her anger and frustration into art.

All this talk about political art makes her sound permanently angry but in fact she’s funny too. She’s explaining that on her Facebook page this week, she posted her thoughts on gay marriage. “Who cares what people do, if they’re not hurting anyone else?” she says. “Love a sheep if you want to. Plenty of people love their dogs. I couldn’t care less.”

She’s hoping her Christian friends will unfriend her so she won’t have to unfriend them.

She has no religion – except perhaps a belief in the brotherhood of man – and dislikes it when Christian acquaintances pray over or for her.

But back to the art. She always painted and drew as a child and has studied and made art ever since she left school. Two years ago, she completed a bachelor of visual and media arts at Monash University’s Churchill campus. Now she draws and makes prints in the kitchen and dining room, with and around her five children. “If they walk on it, they walk on it. I’m not that precious about my work.” The only concession she makes is that she doesn’t paint as much at the moment; print-making is easier when your work is subject to many interruptions.

She divides her work into two categories: more personal work, reflecting herself, her family, her place; and the political work, which she uses to express her frustration.

It often offends people, she knows, but she hopes it will at least start a conversation and create a ripple effect.

Bass Coast is not her traditional country. She is Kamilaroi, Anewan and Dunghatti from Armadale, in New South Wales. When she was 21, and wanting to get away, she closed her eyes and put her finger on a map. It landed in the sea just off Lakes Entrance so she moved there, complete with three kids and two dogs. Later she met a man whose family lived in Wonthaggi so they moved down here.

In the late 1990s, she found the place depressingly monocultural, and couldn’t see where she could fit into it. “I’d grown up in Armadale where these was a university and the community was a melting pot. Wonthaggi felt like the deep south.”

Where her son was bullied at primary school – called a “stinky Abo” – she complained to the principal, who thought it was the “stinky” she found offensive. “People here didn’t even realise ‘Abo’ was derogatory. They thought it was just short for ‘Aborigine’.”

She says there are about 200 people of Aboriginal descent in the whole Bass Coast Shire but no Aboriginal community as such. “They’re hidden.” Because of that, eventually she found herself a de facto representative of the Aborigine peoples, reminding mainstream Bass Coast society that other cultures existed before their own.

One year she persuaded the council to fly the Aboriginal flag during NAIDOC Week and someone set fire to it. Another year, she wrote to the councillors inviting them to attend NAIDOC celebrations, but neither they nor the local newspaper knew what NAIDOC was.

“They thought Sorry Day was the anniversary of Kevin Rudd’s apology to the Stolen Generations. They said they couldn’t come because they required 10 days’ notice and I’d only given them nine. I wrote back asking if they required 10 days’ notice of Christmas Day or Australia Day.”

She laughs. “For a while there I was known as ‘the lady who wrote the letter’. People used to point me out. Now when I’m angry and write something, I usually leave it till the next day to cool down and I read it through.”

She says there is always a cost to trying to live in two worlds. She is pleased to see many more non-Anglos settling in Wonthaggi, gradually opening a window into other worlds.

And she thinks her success in the art world is also reflecting on Wonthaggi. “I feel as though I’m putting Wonthaggi on the black map.”

As for me, remembering the tale of the early Picasso restaurant doodles that were worth a fortune when he became famous, I’m still kicking myself that I didn’t pick up one of the Post It notes with Mahoney’s doodles on it.

COMMENTS

September 9, 2014

Another wonderful edition ! And your article last week about Patrice told us the part of her story that has never been told. Thanks so much for your Post.

Anne Davie, Ventnor

Jobs, Policy and LOST 2014 Patrice Mahoney writes of this work: “These works are a display of my frustration of how our family were lucky we were not beheaded, scalped, taken away and impaled as a warning to others not to enter farming lands, which had been traditional lands of the Nganyaywana country. The word ‘Policy’ represents the White Australia policy; the word ‘Lost’ stands for all those lost, including hundreds of family members; ‘Jobs’ asks why Aboriginal people can only find employment through Aboriginal positions and policies. The number 3 symbolises myself and my siblings. Red is for bloodshed, blue is for secrets, and black the family history.”