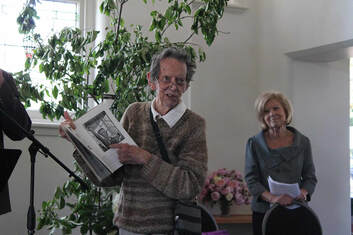

Robert Smith and Wendy Crellin at the launch.

Robert Smith and Wendy Crellin at the launch. NEWS late last year that an art collector had bestowed his collection upon Wonthaggi raised more questions than answers: who, what, where and most of all why.

Last Friday week, in the old Wonthaggi post office, some of us finally got to meet the mysterious benefactor, had a glimpse of the collection and heard the background to his gift.

The plan was for other people to talk about Bob, as his friends call him, but he was having none of it, heading resolutely for the microphone every time there was a break in proceedings or changeover of speaker.

Closing in on 90, an elfin figure with a crooked schoolboy grin, the old thespian commanded the room as he bestowed his gift upon us. At one stage he dramatically pulled prints from a leather-bound folio – Counihan, ST Gill, Durer, among others – laying them in a semi-circle around the floor while he provided a running commentary. He seemed to imply that someone – the councillors? – had been after his works and he was relieved to be handing them over into our care.

What with the film, the theatricality, the back story, those of us in the room felt a sense of wonder and pride at what we were getting: not just the collection but the man.

Wonthaggi arts doyenne Wendy Crellin put it simply: “Bob has come to live among us and give us his collection.”

The key to his generous gift is Noel Counihan, the famous Australian socialist realist painter and printmaker, and the six weeks he spent in Wonthaggi in 1944. Counihan lived with a mining family and each day went underground to sketch the miners at work. In 1947, he produced a set of six linocuts called The Miners.

The following year, a young Western Australian labourer called Bob Smith paid 10 shillings for two Counihan silkscreen prints. In 1963, by which time he was working in a public gallery, Bob began a friendship with Counihan, and in 1981 he published a major catalogue of Counihan’s prints.

In the lead-up to Wonthaggi’s centenary in 2010 the Bass Coast Artists Society decided they would buy a set of Counihan’s Miners series. Wendy Crellin wrote to Bob for advice and later invited him to Wonthaggi to deliver an illustrated lecture on the artist. On the night, his slides were incompatible with the projector, so there was a delay while another was sought. During what could have been an embarrassing delay, he entertained the large audience with a series of Shakespearian monologues.

And so a firm friendship was born, and he developed an affection for Wonthaggi, a town a bit like the poor and undistinguished one where he grew up in Western Australia. Knowing what this place had meant to Counihan added to his affection.

Late last year he gifted his collection to Wonthaggi and in April this year he came to live here. In an email to Wendy early last year he wrote: “I can hardly wait for the moment when I inform Michael Counihan [Noel’s son] that eighty seven of Noel’s works will be at the centre of an important public collection – at the location of those dramatic mining events and associated individuals so superbly captured by Noel in the 1940s.”

Mick Green as usual had done a wonderful job with the film, interweaving interviews with Bob and Wendy Crellin, historical material about Counihan’s Miners series and images from the collection.

In the film, Bob remarks cheerfully that his father wasn’t very interested in children – there was a collective groan of sympathy but no one’s father was very interested in children back then – but that his grandparents introduced him to the world of books. Eventually that love of books led him to the world of art and theatre, the one he was born to inhabit, despite the poor circumstances of his childhood.

The film makes brief mention of a case he took against Flinders University, where he was a senior lecturer for 23 years. After the film, he told us the whole story. He was sacked by Flinders University on the word of two colleagues who claimed he had said certain things on two different occasions.

“But then I produced this!” Bob said, holding up an old passport in triumph. “And it showed I was out of the country when I supposedly said those things.” He sued the university for wrongful dismissal and won substantial damages that enabled him to give up work and to become a serious collector.

Most of his stories were about his triumphs over adversity, but then they are always the best kind.

Like the time the Queensland Gallery sent him to an auction to buy an important Picasso painting. He bought them the painting they wanted and for himself he bought a modest little Picasso drawing – two hands clutching a bunch of flowers – which is now part of our collection.

“Our collection”! It has rather a nice ring to it. For the councillors and ex-councillors in the room, thoughts were turning to the logistics of housing and showing our collection and what it might mean for the future of the town and shire.

The beautiful old post office has too many windows to make an ideal art gallery, but it may be the best we can do in the meantime. With such a big collection, it can only ever be a few works on display at a time.

The long-term dream is a Bass Coast regional art gallery to house the Robert Smith collection and our own now substantial collection of works by local artists. The bigger dream is a cultural precinct incorporating a gallery, a library and a theatre on the secondary school site in McBride Avenue. With the high school scheduled to move to a new site by 2019, the pieces are starting to fall into place.

As Cr Clare Le Serve said, there are years of hard work ahead, but Robert Smith’s gift gives us a wonderful foundation on which to build a case for serious funding from the state and federal governments.