By Catherine Watson

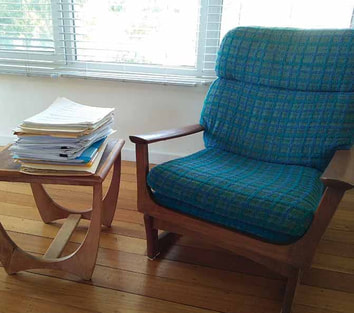

AS ONE of three judges for the Bass Coast Prize for Non-Fiction, I sit down to begin the task one very hot afternoon with mingled anticipation and nervousness.

I’ve done the arithmetic. Forty-two entries, each 5000 to 10,000 words long. Total words 210,000 to 420,000. That’s the equivalent of two long novels or eight short ones. It’s almost as long as War and Peace, and that took me two months to read!

AS ONE of three judges for the Bass Coast Prize for Non-Fiction, I sit down to begin the task one very hot afternoon with mingled anticipation and nervousness.

I’ve done the arithmetic. Forty-two entries, each 5000 to 10,000 words long. Total words 210,000 to 420,000. That’s the equivalent of two long novels or eight short ones. It’s almost as long as War and Peace, and that took me two months to read!

| I’ve got a lot of questions in my mind. How can I be fair to a story if I don’t find the subject interesting? Do I have to read to the end if I don’t like it? The entries are anonymous but what if I recognise the author? What if they’re all terrible? I decide on an initial cursory reading to get a feel for the quality. A “no” pile for entries that are poorly written or dull or don’t meet the criteria for the prize. A “maybe” pile for the others. Then I’ll return to the second pile and read them more carefully. I start from the bottom of the pile. The first two are substantial and serious works, definite maybes. The third is fiction. That’s an easy No. The fourth is a volume of poetry. Is poetry non-fiction? The subject is certainly based on life, and it’s local. There’s nothing in the rules to say entries must be prose. I read the first couple of poems and they’re good. I put it in the Maybe pile. The judges have met a couple of weeks earlier to discuss the criteria. The competition is open to Gippsland writers and entries must pertain to the Gippsland region to qualify for the prize. But what does “pertain” mean exactly? I suggest: “You could write about climate change but it would have to directly relate on a local level somewhere in Gippsland.” | 2019 Bass Coast Prize for Non-Fiction The shortlist

Prizes totalling $10,000 will be awarded for first, second and third, along with four special commendations. The prize winners will be announced at The Gurdies Winery on Sunday, February 9. The special guest is Gippsland-born author Don Watson, acclaimed for works including The Bush, Recollections of a Bleeding Heart, American Journey and Weasel Words. The prize winning entries will be published in the next Post. |

My fellow judge, Geoff Ellis, editor of the Waterline News, offers: “You couldn’t set the story somewhere else and end with ‘And then I came to live in Gippsland’.”

His example proves surprisingly helpful because several of the stories are by writers who have come to live in Gippsland but whose entries have no other local link. Some of these are good, but they go on the No pile.

Our third judge and prize sponsor, Phyllis Papps, stresses that entries must be publication-ready, ie. not require substantial editing or rewriting. I find this very helpful because several otherwise very fine entries are let down by poor editing. The main problem is punctuation: almost always too many commas and not enough full stops.

I know it would only take a few minutes to delete most of those pesky commas but they go on the No pile too.

Others miss out for simple clerical errors: they haven’t supplied a full name, address and contact details. They have only supplied one copy. It really does pay to read the entry conditions one more time and tick everything off.

After my first read-through I find I have 21 entries in the No pile and 21 in the Maybe pile for further consideration.

Now the serious work begins. I read each piece attentively. Has the author got something to say? How well does s/he say it?

Unsurprisingly, many of the entries have an environmental focus: landscape, conservation, Australian bush gardens, profiles of local eco-warriors. Birds are the focus of three very different and interesting essays.

Reflecting the growing interest in Gippsland’s rich Aboriginal history, three essays explore the intersection between the original indigenous occupants and European explorers and settlers. They are very different but all impressive.

Most of the entries are memoirs of one kind or another. There are several memoirs of childhood, which seems to be the period people remember most vividly. One is a political memoir.

For the purposes of an essay, memoir seems to work best with a parallel narrative. A couple use memoir as the basis for a political polemic. Several reflect a political awakening. One segues from personal experience to a rich local history. Another interweaves personal memoir with an imaginative retelling of the story of a Gippsland historical figure.

His example proves surprisingly helpful because several of the stories are by writers who have come to live in Gippsland but whose entries have no other local link. Some of these are good, but they go on the No pile.

Our third judge and prize sponsor, Phyllis Papps, stresses that entries must be publication-ready, ie. not require substantial editing or rewriting. I find this very helpful because several otherwise very fine entries are let down by poor editing. The main problem is punctuation: almost always too many commas and not enough full stops.

I know it would only take a few minutes to delete most of those pesky commas but they go on the No pile too.

Others miss out for simple clerical errors: they haven’t supplied a full name, address and contact details. They have only supplied one copy. It really does pay to read the entry conditions one more time and tick everything off.

After my first read-through I find I have 21 entries in the No pile and 21 in the Maybe pile for further consideration.

Now the serious work begins. I read each piece attentively. Has the author got something to say? How well does s/he say it?

Unsurprisingly, many of the entries have an environmental focus: landscape, conservation, Australian bush gardens, profiles of local eco-warriors. Birds are the focus of three very different and interesting essays.

Reflecting the growing interest in Gippsland’s rich Aboriginal history, three essays explore the intersection between the original indigenous occupants and European explorers and settlers. They are very different but all impressive.

Most of the entries are memoirs of one kind or another. There are several memoirs of childhood, which seems to be the period people remember most vividly. One is a political memoir.

For the purposes of an essay, memoir seems to work best with a parallel narrative. A couple use memoir as the basis for a political polemic. Several reflect a political awakening. One segues from personal experience to a rich local history. Another interweaves personal memoir with an imaginative retelling of the story of a Gippsland historical figure.

*****

I’ve set aside the week between Christmas and New Year to read the entries and am increasingly grateful for the diversion from the unfolding horror of the bushfires.

By the end of the second reading, I’m down to 10 entries. Several of the others I’ve let go reluctantly. They would be worthy winners but there is so much good work here.

Even after the first brief reading, three entries called out to me. A second reading confirms how good they are. I try to separate them with a third reading and I can’t. It’s like comparing apples and oranges. They are all fine pieces of writing. I’m grateful that I don’t have the sole responsibility for picking the winner.

We have decided that each judge will pick a shortlist of six entries. I reluctantly whittle mine down to seven and can’t bear to drop one more. When I mention my difficulty to the other judges, Phyllis responds that she has seven as well, so I leave it be.

We all comment on how much we have enjoyed the reading. We are thrilled at the quality of the entries. It's been a privilege to read them.

By the end of the second reading, I’m down to 10 entries. Several of the others I’ve let go reluctantly. They would be worthy winners but there is so much good work here.

Even after the first brief reading, three entries called out to me. A second reading confirms how good they are. I try to separate them with a third reading and I can’t. It’s like comparing apples and oranges. They are all fine pieces of writing. I’m grateful that I don’t have the sole responsibility for picking the winner.

We have decided that each judge will pick a shortlist of six entries. I reluctantly whittle mine down to seven and can’t bear to drop one more. When I mention my difficulty to the other judges, Phyllis responds that she has seven as well, so I leave it be.

We all comment on how much we have enjoyed the reading. We are thrilled at the quality of the entries. It's been a privilege to read them.

*****

In the second week of January we meet at Phyllis’s place in Rhyll to discuss our shortlists. The moment of truth. If the lists overlap substantially, the winners will pick themselves. If they don’t, this is going to be difficult.

We read out our shortlists. They are almost totally different.

We look at one another in astonishment. We are all thinking the same thought: “How could they have overlooked my favourites?”

Only one entry has been shortlisted by all three judges. Two others have been shortlisted by two of the judges. So now we have 16 works on a combined shortlist!

This would come as no surprise to anyone who belongs to a book club. At its best, reading is a communion between writer and reader. It’s such a private activity. A sentence can move one reader to tears and bore another.

It’s clear we’re in for a long afternoon …

We read out our shortlists. They are almost totally different.

We look at one another in astonishment. We are all thinking the same thought: “How could they have overlooked my favourites?”

Only one entry has been shortlisted by all three judges. Two others have been shortlisted by two of the judges. So now we have 16 works on a combined shortlist!

This would come as no surprise to anyone who belongs to a book club. At its best, reading is a communion between writer and reader. It’s such a private activity. A sentence can move one reader to tears and bore another.

It’s clear we’re in for a long afternoon …