By Christine Grayden

SINCE March is always Women’s History Month, I’m revisiting the life of a remarkable historian I knew personally, and whose family roots grew from deep within Phillip Island’s early settler family trees.

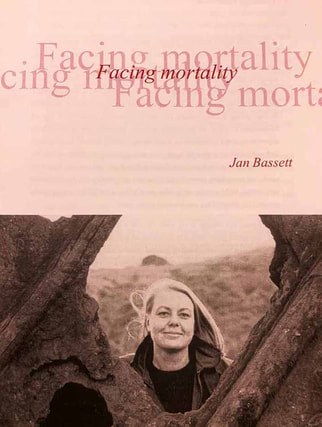

Janice ‘Jan’ Mary Bassett was born the same year as me, in 1953. She crammed much into her 46 years on this planet before passing from breast cancer in 1999. A few months before her death she wrote a personal account of her cancer battle and the highs and lows of life during her cancer journey. The booklet was called Facing Mortality, and featured a beautiful cover photo just as I remember Jan; a few strands of her blond hair are lightly tousled by the wind, as she gazes warmly into the camera through the porthole of the wreck of the Speke, near Kitty Miller Bay. Handed to the many of us attending her funeral, it is a treasured memento.

SINCE March is always Women’s History Month, I’m revisiting the life of a remarkable historian I knew personally, and whose family roots grew from deep within Phillip Island’s early settler family trees.

Janice ‘Jan’ Mary Bassett was born the same year as me, in 1953. She crammed much into her 46 years on this planet before passing from breast cancer in 1999. A few months before her death she wrote a personal account of her cancer battle and the highs and lows of life during her cancer journey. The booklet was called Facing Mortality, and featured a beautiful cover photo just as I remember Jan; a few strands of her blond hair are lightly tousled by the wind, as she gazes warmly into the camera through the porthole of the wreck of the Speke, near Kitty Miller Bay. Handed to the many of us attending her funeral, it is a treasured memento.

Jan was the daughter of Frank and Una Lyons (nee Coels). Una’s mother was a descendent of Sarah and Joseph Richardson, who came to Phillip Island from the first closer settlement ballot in 1868. Jan's grandmother Edith married builder Rudolph Coels in 1927. Una was their only child.

The Lyons family of Frank, Una and their two daughters – Jan and Susan – first lived in Glen Iris from where Jan travelled daily to attend St Michael’s secondary school in St Kilda. When Frank was given the task of developing the Irymple Technical College, then the large TAFE college in Mildura, Jan decided against boarding at St Michael’s and opted to attend school in Mildura where she excelled as a student, head of house, head of the debating team and head prefect.

Jan could probably have studied anything, but studied history at Melbourne University. This was in the 1970s era of such luminaries as Geoffrey Blainey and Greg Denning, and where her main mentor was Lloyd Robson. I had also developed a passion for history, but studying simultaneously at La Trobe University meant Jan and I only spoke occasionally about our studies.

She and I knew each other through both spending our holidays only a short distance apart at Ventnor – Jan at her grandparents’ farm, ‘The Pines’ on Ventnor Road, and me with my uncle Keith in Lyall Street. We were all related through marriage.

I became a teacher and wrote community history. Jan became a professional academic researcher, though she wrote both academic and popular history.

She had taken on a number of challenging historical research and writing projects and had written nine books by the time she became ill. Commencing with The Home Front, 1914-1918, a book aimed at schools, her love of the sea and travel was reflected in her next books, which included Great Southern Landings: an anthology of Antipodean Travel; Great Explorations: an Australian anthology; and Wrecked! Mysteries and Disasters at Sea. She also compiled three versions of the Oxford Dictionary of Australian History.

However, it was through her ground-breaking work on army nurses where Jan and I have now merged, over 20 years since the cancer took her.

My colleague John Jansson and I have been working towards producing a book about the 120 or so servicemen and women from World War One whose lives intersected in some way with Phillip Island. Some were born here, some lived here before the war, some arrived at some stage after the war.

One was Australian Army Nurse Jane Eleanor Turner, who served mainly in the incredibly difficult, swampy and malaria-ridden environment of the Salonika hospital camps in 1917-1918. After returning, Jane served as Matron at Warley Hospital, Cowes in 1925 before moving on to other nursing posts.

The Lyons family of Frank, Una and their two daughters – Jan and Susan – first lived in Glen Iris from where Jan travelled daily to attend St Michael’s secondary school in St Kilda. When Frank was given the task of developing the Irymple Technical College, then the large TAFE college in Mildura, Jan decided against boarding at St Michael’s and opted to attend school in Mildura where she excelled as a student, head of house, head of the debating team and head prefect.

Jan could probably have studied anything, but studied history at Melbourne University. This was in the 1970s era of such luminaries as Geoffrey Blainey and Greg Denning, and where her main mentor was Lloyd Robson. I had also developed a passion for history, but studying simultaneously at La Trobe University meant Jan and I only spoke occasionally about our studies.

She and I knew each other through both spending our holidays only a short distance apart at Ventnor – Jan at her grandparents’ farm, ‘The Pines’ on Ventnor Road, and me with my uncle Keith in Lyall Street. We were all related through marriage.

I became a teacher and wrote community history. Jan became a professional academic researcher, though she wrote both academic and popular history.

She had taken on a number of challenging historical research and writing projects and had written nine books by the time she became ill. Commencing with The Home Front, 1914-1918, a book aimed at schools, her love of the sea and travel was reflected in her next books, which included Great Southern Landings: an anthology of Antipodean Travel; Great Explorations: an Australian anthology; and Wrecked! Mysteries and Disasters at Sea. She also compiled three versions of the Oxford Dictionary of Australian History.

However, it was through her ground-breaking work on army nurses where Jan and I have now merged, over 20 years since the cancer took her.

My colleague John Jansson and I have been working towards producing a book about the 120 or so servicemen and women from World War One whose lives intersected in some way with Phillip Island. Some were born here, some lived here before the war, some arrived at some stage after the war.

One was Australian Army Nurse Jane Eleanor Turner, who served mainly in the incredibly difficult, swampy and malaria-ridden environment of the Salonika hospital camps in 1917-1918. After returning, Jane served as Matron at Warley Hospital, Cowes in 1925 before moving on to other nursing posts.

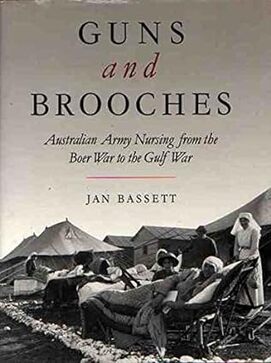

| If it was not for Jan Bassett’s wonderful 1992 book Guns and Brooches: Australian Army Nursing from the Boer to the Gulf War, many of us historians would not now have a starting point for our research about these amazingly resilient nurses. On Saturday 1 November 1997, despite already being quite sick with cancer, Jan bravely stood in front of 300 locals at the Rhyll Mechanics Hall and officially launched the labour of community love which had become the Rhyll history: Within the Plains of Paradise. During that speech Jan spoke of the connections of the island’s town and farming communities through family and shared hardships. She told us of her latest project – a ‘personal history’ recounting her relationship with Phillip Island through rich memories. This book became The Facing Island, that would tie together threads between Wilson Tong of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force who threw a note in a bottle overboard on his way to service in the bloodbath that was the Western Front; her beloved grandmother Edith Coels on Phillip Island who came in possession of the note and wrote to the soldier’s mother, initiating a five year long letter-writing relationship between Edith and Wilson; and Jan’s own experience of Phillip Island, while trying to make sense of the huge losses suffered during the Great War about which she had by then studied so much. After the crowd dispersed, Jan and I took a quiet 15 minutes to catch up on each other’s lives. Despite Jan being the most composed person I have ever known, I will never forget the fear in her eyes as she told me the reality of her situation. |

Jan completed The Facing Island before she died, but was unable to see it through to publication. That was done for her posthumously by her friend Peter Rose and her husband Andrew Demetriou, and published in 2003.

Edith’s chiffonier, in which Jan found a secret drawer containing Wilson Tong’s letters to her grandmother.

Edith’s chiffonier, in which Jan found a secret drawer containing Wilson Tong’s letters to her grandmother. It is a compelling book of letters, in which Jan writes to her long-dead grandmother - but often imagined as a young woman - in response to a bundle of saved letters Jan found in a secret drawer of Edith’s chiffonier. The letters were all written from the front by a traumatised yet ever-hopeful Wilson.

Often Jan’s letters within the book to her grandmother raise more questions than they answer, which was no doubt reflective of the hard place in which Jan found herself, and her empathy with Wilson, who, with bomb blasts all around him, faced mortality every second; just as Jan was herself.

Jan left us while still really just at the start of her career as an historian. But the legacy she leaves dramatically increases our knowledge and understanding of the enormous contribution made by Australian army nurses in situations of extreme deprivation, hardship and danger. Both Jan Basset and those nurses, such as Jane Turner, all deserve our utmost respect this Women’s History Month.

Often Jan’s letters within the book to her grandmother raise more questions than they answer, which was no doubt reflective of the hard place in which Jan found herself, and her empathy with Wilson, who, with bomb blasts all around him, faced mortality every second; just as Jan was herself.

Jan left us while still really just at the start of her career as an historian. But the legacy she leaves dramatically increases our knowledge and understanding of the enormous contribution made by Australian army nurses in situations of extreme deprivation, hardship and danger. Both Jan Basset and those nurses, such as Jane Turner, all deserve our utmost respect this Women’s History Month.