By Christine Grayden

LAST month when I wrote about Dr Jan Bassett’s experience of finding a bundle of letters in her grandmother’s chiffonier - letters which turned out to be from a New Zealand soldier during World War One - I certainly didn’t think a similar thing would happen to me. But recently I was sitting with my old mate Laurie Dixon, going through the names of 118 World War One servicemen and one nurse associated with Phillip Island, who John Jansson and I have found in the war records.

I was hopeful Laurie might have at least some family memory stories to add to the information we have on these people. When we got to the Dominick brothers who had worked for Jessie McGregor (Janet, married name Watson), Laurie said: “Christine, I’ve got an album of post cards those boys sent to old Jessie when they were away. I think she was their foster mother or something like that.” It was one of those Bingo! moments all researchers live for.

LAST month when I wrote about Dr Jan Bassett’s experience of finding a bundle of letters in her grandmother’s chiffonier - letters which turned out to be from a New Zealand soldier during World War One - I certainly didn’t think a similar thing would happen to me. But recently I was sitting with my old mate Laurie Dixon, going through the names of 118 World War One servicemen and one nurse associated with Phillip Island, who John Jansson and I have found in the war records.

I was hopeful Laurie might have at least some family memory stories to add to the information we have on these people. When we got to the Dominick brothers who had worked for Jessie McGregor (Janet, married name Watson), Laurie said: “Christine, I’ve got an album of post cards those boys sent to old Jessie when they were away. I think she was their foster mother or something like that.” It was one of those Bingo! moments all researchers live for.

Percival James Dominick was born in South Melbourne in 1889 and his brother Francis Joseph Dominick was born in South Melbourne in 1893, to Croatian-born Paolo Domancic and Lucy Helena (nee Perkins). The brothers were working for Jessie McGregor on her farm near Pyramid Rock on Phillip Island. We’ve been unable to find at what stage their mother became ill, but she died in 1915, when the brothers were aged in their twenties. Why Percival in particular formed such a strong bond with Jessie is still a mystery to us.

Jessie herself was a legend on Phillip Island. Known as “the flower of Phillip Island” in her younger years, because apparently she was rather lovely to behold, she and her brother Charlie ran the family farm after their early settler parents died. Jessie was tough and independent, her marriage apparently lasting only weeks, and she died well in her nineties in 1963.

Both Dominick brothers enlisted within a few weeks of each other in October 1916. Francis died at Passchendaele Ridge, Ypres, at the age of 22 in August 1917, within 12 months of enlisting. Percival saw action in several of the major battle areas, eventually developing trench fever, then appendicitis. He was still suffering from appendicitis when sent home in November 1918, which must have been a very painful sea voyage.

Percival – let’s call him Percy - Service number 6991, enlisted on 4 October 1916 at Melbourne with the 23/6th Battalion and embarked from Melbourne on 23 November 1916 on HMAT Hororata and disembarked at Plymouth on 29 January 1917. The post cards in the album commence once he arrives at Albany, WA, where they must have had shore leave, and where Percy purchased some post cards to send to his “Dear Mother”, always signing off “Your loving son”, or “Your loving foster son”. Clearly Percy and his fellow servicemen struck it lucky with their trip. Some of the other troop ships also carried horses, and conditions were then cramped, putrid and unhygienic, especially below decks where the men’s bunks were.

By Albany, Percy was in high spirits, writing “We’re well and having a real good trip … a splendid boat, with good food and plenty of it, and plenty of games on board.”

Jessie herself was a legend on Phillip Island. Known as “the flower of Phillip Island” in her younger years, because apparently she was rather lovely to behold, she and her brother Charlie ran the family farm after their early settler parents died. Jessie was tough and independent, her marriage apparently lasting only weeks, and she died well in her nineties in 1963.

Both Dominick brothers enlisted within a few weeks of each other in October 1916. Francis died at Passchendaele Ridge, Ypres, at the age of 22 in August 1917, within 12 months of enlisting. Percival saw action in several of the major battle areas, eventually developing trench fever, then appendicitis. He was still suffering from appendicitis when sent home in November 1918, which must have been a very painful sea voyage.

Percival – let’s call him Percy - Service number 6991, enlisted on 4 October 1916 at Melbourne with the 23/6th Battalion and embarked from Melbourne on 23 November 1916 on HMAT Hororata and disembarked at Plymouth on 29 January 1917. The post cards in the album commence once he arrives at Albany, WA, where they must have had shore leave, and where Percy purchased some post cards to send to his “Dear Mother”, always signing off “Your loving son”, or “Your loving foster son”. Clearly Percy and his fellow servicemen struck it lucky with their trip. Some of the other troop ships also carried horses, and conditions were then cramped, putrid and unhygienic, especially below decks where the men’s bunks were.

By Albany, Percy was in high spirits, writing “We’re well and having a real good trip … a splendid boat, with good food and plenty of it, and plenty of games on board.”

The big adventure continued with shore leave at Cape Town and a visit to Durban, from where Percy sent Jessie several post cards, one wishing her “A Happy Christmas and a Happy New Year from your loving son Percy at sea”.

In Durban, the sight of a “Richsha-puller” in African tribal dress must have been extraordinary for Percy, who wrote “I wish you were here with me to have a ride in a Ricksha with me and what a good time we would have but never mind. When I return we will have a trip together”. Jessie does not seem to have travelled far in her life, and apparently never learnt to drive.

Their ship did not go via the Middle East, but straight to England, where again they must have had shore leave. Percy sent many post cards from England and even a few from Scotland. As a farm lad he was fascinated by the thatched roofs of the cottages in the villages. He wrote to Jessie that “The work is most beautiful to see how it’s done and when I get back I will show you how it’s done.”

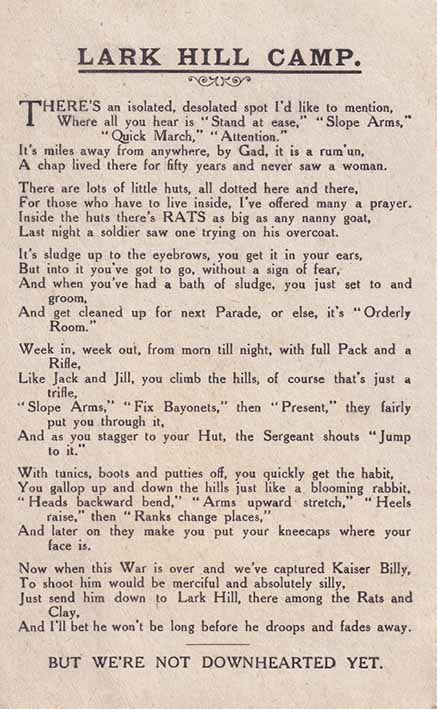

The camp where they trained was a very different story though, and it is from this post card on that the reality of the war sets in for Percy.

He wrote “Just a card to show you what sort of place our camp is one long plain and a fearful cold place nothing but snow rain and wind but I think I must be made of cast iron to bear it”. Just to emphasise the conditions he also sent a post card of a poem about the camp:

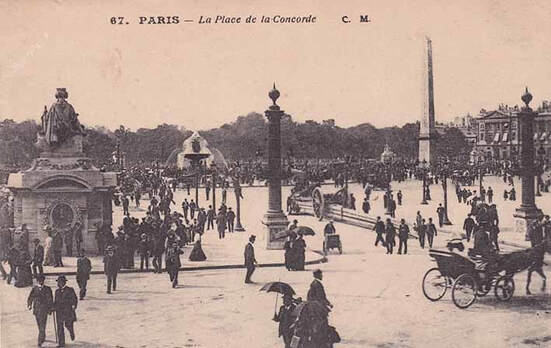

Once in France, only one ‘view’ post card is sent, to show Jessie a world she could hardly imagine of a city she had certainly heard much about:

The rest of the post cards Percy sent Jessie were mainly of sentimental, flowery verse with short messages on the back. He relates how the Red Cross were providing welcome hot meals during breaks from their times on the front. Then there comes a post card from England, where Percy has been sent in a fairly bad way with ‘trench feet’ fever and appendicitis, which back in that time before antibiotics was as serious as a severe limb injury. He tells her “I thought I was done for” but that they are feeding him well and the games room is well equipped. Many grand old homes in England were made over to be war hospitals or convalescent homes, so that would account for the games room.

Percy must have still been in pain when he left England, but he wrote to Jessie in positive mood:

Percy must have still been in pain when he left England, but he wrote to Jessie in positive mood:

The album is full of wonderful post cards and messages. I’ve barely scratched the surface here. We have no way of knowing if Jessie wrote back to “her boys”. Nor do we know if Percy knew Jessie had entered into a disastrous marriage in his absence. But we are very lucky to have this album, which Laurie rescued when he was given the job of demolishing Jessie’s house some years after she had died.

As for Percy, he married Myrtle Skinner at Burnley on 27 July 1919 and lived in St Kilda and later in Prahran. Percy died on 1st January 1951 at Heidelberg and was buried in the New Cheltenham Cemetery. All that’s another story, which John Jansson and I will tell in a bit more detail in the book.

So many Percys and Franks left our shores over 100 years ago to fight for King, and Commonwealth, and mothers and sweethearts at Home. Many like Percy came home, many like Frank did not.

Lest we forget.

As for Percy, he married Myrtle Skinner at Burnley on 27 July 1919 and lived in St Kilda and later in Prahran. Percy died on 1st January 1951 at Heidelberg and was buried in the New Cheltenham Cemetery. All that’s another story, which John Jansson and I will tell in a bit more detail in the book.

So many Percys and Franks left our shores over 100 years ago to fight for King, and Commonwealth, and mothers and sweethearts at Home. Many like Percy came home, many like Frank did not.

Lest we forget.