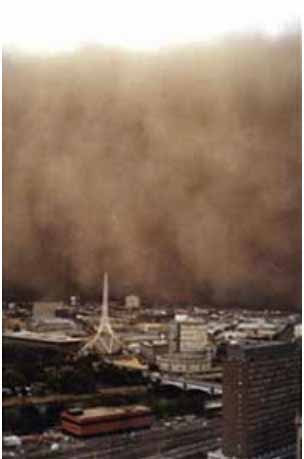

On February 8 1983, millions of tonnes of topsoil from cleared land in western Victoria and South Australia was deposited on Melbourne. Photo: Victorian Resources Online

On February 8 1983, millions of tonnes of topsoil from cleared land in western Victoria and South Australia was deposited on Melbourne. Photo: Victorian Resources Online IN 1983, I quit work and took a year to learn more about ecology at Roseworthy Agricultural College in South Australia, then celebrating its centenary year. Natural resources management rather than agricultural production was my preferred study, and my thesis was about trees on farms.

Remember 1983? The defining moment of the drought was the dust storm that blacked out Melbourne, followed on February 16 by the Ash Wednesday bushfires that swept from Adelaide through Victoria.

On February 17 I drove to South Australia. It was still hot, and I cooked the motor of my tiny Mazda 1000 ute at Talem Bend and hitch hiked through the ravaged Adelaide hills to begin my studies.

For a farm boy from the high rainfall Yarra Valley, the flat windswept wheat and sheep farms, in the driest, most cleared state in the world’s driest continent, were a shock.

South Australia was the first state to reverse the established order. On May 12 1983, overnight, with no compensation, South Australia enacted planning controls. “As of right” clearing by farmers was replaced by a government-sanctioned permit system.

As a gauge of how extreme the situation was, not even the state's peak farming body questioned the need for the controls. Some agricultural areas had well under 10 per cent indigenous vegetation left.

The VAGO report concluded: “Councils are not adequately managing native vegetation clearing on private land and have not taken effective action against unauthorised clearing.”

Having subdued the vegetation masterfully we are reaping the reward: extinction, first local, then general. How does it happen? One animal, one plant at a time.

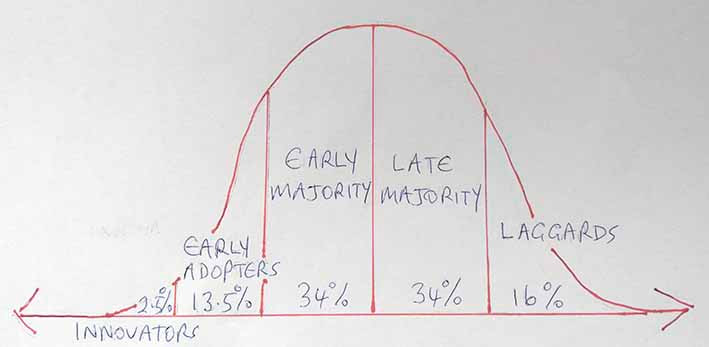

At Roseworthy I was introduced to the bell curve of adoption. It’s a simple line graph that shows the rate over time of adoption of new products or ideas.

“As banks all over the world start cutting off lending to coal miners, Jefferies Group stands out as a clear climate laggard, apparently willing to be the lender of last resort for these polluting companies.” Market Forces, March 23, 2024

The indigenous vegetation retention of Bass Coast Shire today is similar to the retention rates of the agricultural areas of South Australia in 1983, with just 2 to 14% left (depending on the source), most of it modified and fragmented. The few gems that have inadvertently survived, such as the Western Port Woodlands, are on the brink of destruction if sand mining continues as it has done. Meanwhile, in Corinella, decades of rehabilitation work along the foreshore is at risk, with apparent support from Victoria’s own Environment Department.

Two things give me hope. Last year I heard Bass Coast’s environmentalist of the year, Paul Spiers, say he had seen a massive increase in the amount and quality of native vegetation in our shire over the past three decades. You only have to look at the Bass Hills to see the truth of Paul’s statement. Those previously bald hills – cleared for farming early in European settlement – are now starting to look like a patchwork quilt with the dark green signifying mass plantings in the gullies.

1100 hectares represents 1.27% of Bass Coast’s total land area of 86,600 hectares. When we have so little left, it's a significant gain. But it’s not a net gain. Always, landscape wide, the incremental, unwavering removal continues. On any given week one sees a farm fence replaced, a road reconstructed, a pest plant poorly sprayed.

It is not that each individual action is not justifiable and even reasonable when taken in isolation. Systemic degradation is the cumulative effect of each of those isolated actions, delivered over decades. One plant at a time.

Should the laggard be demonised? Demonisation is such a convenient get out. It is similar to the great “they”, as in the “they … should, should’ve, could’ve” school. They are everybody else but you. The blame game is the preserve of the lazy. Extinction is our issue.

Who can blame farmers for preferring the clarity of maximising profit over the minefield of conservation? If we are serious about retention, then the State should support them to change their practices by recognising and compensating their sacrifice for the public good.

Ed Thexton is president of the South Gippsland Conservation Society.