Ayr Creek, Inverloch. Photos: Ed Thexton

Ayr Creek, Inverloch. Photos: Ed Thexton By Ed Thexton

I’M A country kid whose youth was spent on the Woori Yallock Creek at Yellingbo that is the last holdout of the helmeted honeyeater. Little did I know my local creek was a rare exception, its floral and faunal riches absent from most creeks of agricultural Victoria.

By chance I now find myself in Inverloch on the Ayr Creek. More a much-altered drainage line than creek really. But no matter how humble, it’s our creek. Thirty minutes ago I was in it, pulling out weeds and contemplating this writing. I’m 65 this birthday so the flower of youth is wilted, helped no doubt by the bee that thought fit to sacrifice its life for the benefit of my skull. I mused over what the hell I was doing with my holed gumboot in the effluent of Inverloch.

I’M A country kid whose youth was spent on the Woori Yallock Creek at Yellingbo that is the last holdout of the helmeted honeyeater. Little did I know my local creek was a rare exception, its floral and faunal riches absent from most creeks of agricultural Victoria.

By chance I now find myself in Inverloch on the Ayr Creek. More a much-altered drainage line than creek really. But no matter how humble, it’s our creek. Thirty minutes ago I was in it, pulling out weeds and contemplating this writing. I’m 65 this birthday so the flower of youth is wilted, helped no doubt by the bee that thought fit to sacrifice its life for the benefit of my skull. I mused over what the hell I was doing with my holed gumboot in the effluent of Inverloch.

Really, I was gardening. Extracting one plant, in this case wandering trad (formerly known to many of us as wandering Jew), a native of Brazil, to create opportunity for others. I thought of the artificiality of our reductionist approach to education, of how forestry, agriculture and horticulture are siloed when in their true essence they are all just forms of applied interventionist ecology. Creek rehabilitation is interventionist ecology too.

Ed in the Ayr. Photo: Terry Melvin

Ed in the Ayr. Photo: Terry Melvin I’d spent four hours in my wetsuit up to my chest mid-creek in the high flow of Sunday afternoon. With my gloved hands I wrenched off rafts of soft, pliant wandering trad stems and sent them to their ultimate demise downstream. High fast waterflow is a terribly efficient means of mass transport and salt water is lethal.

After science training in horticulture and ecology I’d applied my learning to waterways, specifically the rehabilitation of riparian vegetation. Riparian – from the Latin ripa for bank; rehabilitation – the process of restoring to health as best as possible.

When I started in the early 1980s there was no template. My company focused on the assessment and design of rehabilitation processes for riparian vegetation. We worked on disturbed urban and agricultural waterways across south-eastern Australia. We did it on foot and by helicopter, boat and hovercraft. We worked at any scale – site, stream, catchment or region. If it was riparian vegetation, I was into it.

The Ayr Creek is the beneficiary. Learning by doing taught me that success in waterway vegetation rehabilitation is half technical and half people engagement, particularly in urban and agricultural areas. The other great learning is that any rehabilitation worth its salt needs a decade or more.

Now, as president of the South Gippsland Conservation Society (SGCS), in the midst of a climate emergency and an extinction crisis, I feel pressure “not to sweat the small things”.

After science training in horticulture and ecology I’d applied my learning to waterways, specifically the rehabilitation of riparian vegetation. Riparian – from the Latin ripa for bank; rehabilitation – the process of restoring to health as best as possible.

When I started in the early 1980s there was no template. My company focused on the assessment and design of rehabilitation processes for riparian vegetation. We worked on disturbed urban and agricultural waterways across south-eastern Australia. We did it on foot and by helicopter, boat and hovercraft. We worked at any scale – site, stream, catchment or region. If it was riparian vegetation, I was into it.

The Ayr Creek is the beneficiary. Learning by doing taught me that success in waterway vegetation rehabilitation is half technical and half people engagement, particularly in urban and agricultural areas. The other great learning is that any rehabilitation worth its salt needs a decade or more.

Now, as president of the South Gippsland Conservation Society (SGCS), in the midst of a climate emergency and an extinction crisis, I feel pressure “not to sweat the small things”.

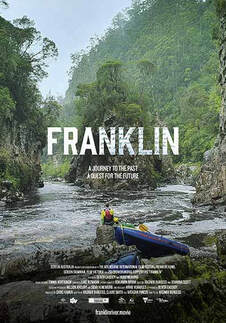

Wonthaggi Cinema, Sunday, Oct 16, 2pm

Wonthaggi Cinema, Sunday, Oct 16, 2pm With no hope of resolving that bind I can offer inspiration to go forth and be bold, just as the Franklin River protesters did when I was starting my riparian journey in 1983.

SGCS will host the screening of the feature-length film Franklin at the Wonthaggi Cinema on Sunday October 16 at 2pm. It is compelling, made by the son of a protester and shot as he canoed the Franklin River Tasmania in all its glory. Take heart and be inspired!

Therein lies the conundrum. Saving the Franklin River was a conservation victory for the ages, but it relied on attention to many small details. In a similar way to removing the few remaining stems of wandering trad, that is the foundation upon which greater successes rely. The very fact that we are local means we can do attention to detail very well.

I was back in the Ayr Creek this afternoon removing the remaining stems of wandering trad from the bank. At this small scale it’s gardening with an aim that goes beyond the mere aesthetic, to create habitat for our birds to help hold back the tide of extinction. To move the creek vegetation from the homogeneity of an overwhelming weed species, built up over decades, to create opportunity for structural and species diversity provided by indigenous planting and colonisation by ferns.

Anyone with an interest in the detail of gardening and habitat creation is welcome to contact me on [email protected] and come on down for an hour or two. I can assure you it’s very therapeutic.

SGCS will host the screening of the feature-length film Franklin at the Wonthaggi Cinema on Sunday October 16 at 2pm. It is compelling, made by the son of a protester and shot as he canoed the Franklin River Tasmania in all its glory. Take heart and be inspired!

Therein lies the conundrum. Saving the Franklin River was a conservation victory for the ages, but it relied on attention to many small details. In a similar way to removing the few remaining stems of wandering trad, that is the foundation upon which greater successes rely. The very fact that we are local means we can do attention to detail very well.

I was back in the Ayr Creek this afternoon removing the remaining stems of wandering trad from the bank. At this small scale it’s gardening with an aim that goes beyond the mere aesthetic, to create habitat for our birds to help hold back the tide of extinction. To move the creek vegetation from the homogeneity of an overwhelming weed species, built up over decades, to create opportunity for structural and species diversity provided by indigenous planting and colonisation by ferns.

Anyone with an interest in the detail of gardening and habitat creation is welcome to contact me on [email protected] and come on down for an hour or two. I can assure you it’s very therapeutic.