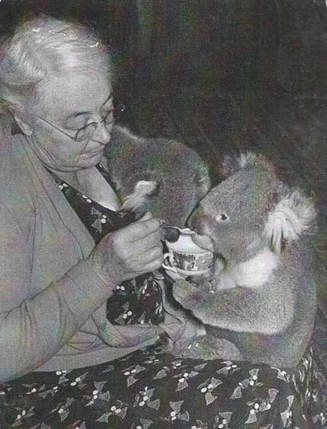

Florence ('Zing') Oswin-Roberts cares for a koala at her home, ‘Broadwater’, Cowes

Florence ('Zing') Oswin-Roberts cares for a koala at her home, ‘Broadwater’, Cowes Many a Phillip Island farmer about to cut down a tree looked both ways to make sure ‘Zing’ Oswin-Roberts wasn’t watching. Zing’s story is told in a new book profiling 23 women who have fought to protect the island’s natural environment over the past century.

By Mary Karney

FLORENCE Oswin was the daughter of a selector at Balnarring on the Mornington Peninsula. She was born in 1875, the eldest girl in a family of eight. Her father's selection of 278 acres in what is now Merricks was a forested area of giant messmate and manna gums. In her childhood she would have witnessed the destruction of these forests to make way for crops, orchards, and grazing pastures, and their replacement by European trees. In those days there was still an abundance of native animals, including koalas, which were to play an important part in her future life. It seems likely that her love of trees and animals began early in her life.

The family property was sold in 1910. Florence, more commonly known as "Zing", was experienced in hospitality management. She had worked at the Windsor Hotel (then the Grand Coffee Palace) and her brother's guest house in Mildura, where she met her future husband 'Rajah' Roberts. In 1912 she bought Broadwater, a large house standing on two and a half acres at Cowes, Phillip Island, on the comer of Lovers Walk, Dunsmore Road and Chapel Street, and joined by two of her sisters, converted it into a guest house.

Broadwater was built in the 1890s by the Henty-Wilson family as a holiday home. It was in an ideal location for a guest house, being a short walk up Lovers Walk or Chapel Street to the township, and just across Lovers Walk from the beach. In those days before erosion had taken its toll, the way to the beach was a sandy path winding through tall sandhills covered in Coast Banksia and Teatree. The grounds of Broadwater were also largely uncleared.

The guest house flourished, and as time went by, Zing had to add more and more buildings for accommodation, but by this time she had become a passionate conservationist, and rather than cut down trees, she dotted thatched bungalows through the grounds for sleeping quarters, though adding to the original house with large dining, lounge and entertainment areas.

Zing drove a small grey car, 'The Beetle'. Many a farmer, about to cut down a tree looked both ways to make sure The Beetle with Zing at the wheel was not approaching in a cloud of dust along a dirt road to catch him in the act of this vandalism. She had the courage of her convictions and was not afraid to intervene to save a tree.

Zing married Eustace George Roberts (Rajah) in 1924 after a long-term romance. He was an electrical engineer and worked for many years in Western Australia where Zing joined him every year in the 'off-season’ of tourism on Phillip Island. She was enraptured by the colourful vegetation of the West. Rajah was also interested in the natural environment and her work with the koalas.

In those days koalas were plentiful on Phillip Island, though they were not originally indigenous there, and had been introduced from the mainland. On a walk up Chapel Street to the village you were certain to see several perched in roadside manna gums. But 1939 was the year of widespread bushfires throughout Victoria, and Phillip Island was not spared. Zing drove round rescuing burnt or starving koalas in the blackened countryside. Broadwater became a koala hospital with hammocks set up in the guest rooms where she tended victims. She hunted for intact manna or peppermint trees, the staples of a koala's diet, to bring home leaves to feed them.

FLORENCE Oswin was the daughter of a selector at Balnarring on the Mornington Peninsula. She was born in 1875, the eldest girl in a family of eight. Her father's selection of 278 acres in what is now Merricks was a forested area of giant messmate and manna gums. In her childhood she would have witnessed the destruction of these forests to make way for crops, orchards, and grazing pastures, and their replacement by European trees. In those days there was still an abundance of native animals, including koalas, which were to play an important part in her future life. It seems likely that her love of trees and animals began early in her life.

The family property was sold in 1910. Florence, more commonly known as "Zing", was experienced in hospitality management. She had worked at the Windsor Hotel (then the Grand Coffee Palace) and her brother's guest house in Mildura, where she met her future husband 'Rajah' Roberts. In 1912 she bought Broadwater, a large house standing on two and a half acres at Cowes, Phillip Island, on the comer of Lovers Walk, Dunsmore Road and Chapel Street, and joined by two of her sisters, converted it into a guest house.

Broadwater was built in the 1890s by the Henty-Wilson family as a holiday home. It was in an ideal location for a guest house, being a short walk up Lovers Walk or Chapel Street to the township, and just across Lovers Walk from the beach. In those days before erosion had taken its toll, the way to the beach was a sandy path winding through tall sandhills covered in Coast Banksia and Teatree. The grounds of Broadwater were also largely uncleared.

The guest house flourished, and as time went by, Zing had to add more and more buildings for accommodation, but by this time she had become a passionate conservationist, and rather than cut down trees, she dotted thatched bungalows through the grounds for sleeping quarters, though adding to the original house with large dining, lounge and entertainment areas.

Zing drove a small grey car, 'The Beetle'. Many a farmer, about to cut down a tree looked both ways to make sure The Beetle with Zing at the wheel was not approaching in a cloud of dust along a dirt road to catch him in the act of this vandalism. She had the courage of her convictions and was not afraid to intervene to save a tree.

Zing married Eustace George Roberts (Rajah) in 1924 after a long-term romance. He was an electrical engineer and worked for many years in Western Australia where Zing joined him every year in the 'off-season’ of tourism on Phillip Island. She was enraptured by the colourful vegetation of the West. Rajah was also interested in the natural environment and her work with the koalas.

In those days koalas were plentiful on Phillip Island, though they were not originally indigenous there, and had been introduced from the mainland. On a walk up Chapel Street to the village you were certain to see several perched in roadside manna gums. But 1939 was the year of widespread bushfires throughout Victoria, and Phillip Island was not spared. Zing drove round rescuing burnt or starving koalas in the blackened countryside. Broadwater became a koala hospital with hammocks set up in the guest rooms where she tended victims. She hunted for intact manna or peppermint trees, the staples of a koala's diet, to bring home leaves to feed them.

Zing found a dead female koala with a baby in her pouch on the side of a road. She brought home the baby. Two of the many well-known visitors to Broadwater were the naturalists Crosbie Morrison and Charles Barrett, and with their advice she managed to rear the orphan. lt was illegal for an individual to keep a koala in captivity, so with strings pulled by other prominent guests and friends of Zing, a special bill was passed through the State Parliament allowing her custody of her foundling.

This koala was named Edward, though later found to be a female. She lived a pampered life at Broadwater, and far from being a captive, resisted any attempt to restore her to the wild. She became famous during the war, making appearances with Zing at functions in Melbourne for the war effort. A large old manna gum tree outside the Broadwater gate was her special tree, and a plaque was attached to the trunk after her death: 'Edward’s Tree’. Edward died in 1944 of Chlamydia, a disease which seriously depleted the population of koalas on the island.

Every summer towards the end of the 'Season' Zing set aside two weeks when she filled Broadwater with disadvantaged children from Melbourne and Adelaide. During this time, as well as having the beach close by, Zing hired buses to take the children on trips and picnics to other parts of the Island, and organised entertainments at Broadwater such as dances in the games room with local bands providing the music. This would have been a one-time only for most of those children. Zing charged nothing for this holiday.

Zing bought 150 acres of land on Harbisons Road for a koala reserve, the Oswin Roberts Reserve', and had it planted out with manna gums. She bequeathed money in her will for the continued upkeep of this reserve. Though this financial bequest has long been finalised, her reserve is still a tourist attraction today. She was undoubtedly ahead of her time as a woman devoted to conservation.

This koala was named Edward, though later found to be a female. She lived a pampered life at Broadwater, and far from being a captive, resisted any attempt to restore her to the wild. She became famous during the war, making appearances with Zing at functions in Melbourne for the war effort. A large old manna gum tree outside the Broadwater gate was her special tree, and a plaque was attached to the trunk after her death: 'Edward’s Tree’. Edward died in 1944 of Chlamydia, a disease which seriously depleted the population of koalas on the island.

Every summer towards the end of the 'Season' Zing set aside two weeks when she filled Broadwater with disadvantaged children from Melbourne and Adelaide. During this time, as well as having the beach close by, Zing hired buses to take the children on trips and picnics to other parts of the Island, and organised entertainments at Broadwater such as dances in the games room with local bands providing the music. This would have been a one-time only for most of those children. Zing charged nothing for this holiday.

Zing bought 150 acres of land on Harbisons Road for a koala reserve, the Oswin Roberts Reserve', and had it planted out with manna gums. She bequeathed money in her will for the continued upkeep of this reserve. Though this financial bequest has long been finalised, her reserve is still a tourist attraction today. She was undoubtedly ahead of her time as a woman devoted to conservation.

* * * * *

Florence Oswin-Roberts’ story is one of 23 featured in Women in Conservation on Phillip Island, edited by Christine Grayden and published by the Phillip Island Conservation Society last month.

What comes across in this inspiring collection of profiles is the selfless devotion of these women not to building private fortunes or well-paid careers but to nurturing and protecting “their place”, the remaining few wild places on Phillip Island.

There is no sense of sacrifice but immense satisfaction in protecting the island’s fragile environment, pride in the collective achievements, and pleasure in working with others for a worthwhile cause. For all the hundreds or thousands of hours of back-breaking work (physical and mental) they put in, these women invariably say they have gained more than they gave.

For the island’s environmental crusaders, there have been countless campaigns, many notable victories (the buyback of land on the ill-conceived Summerland estate, the campaign against a container port at Hastings, the establishment of a koala sanctuary, to name a few) and some disappointments, not least the Narre Warren-type housing estates now sprouting up around Cowes.

As the campaigners have learned, no victory is ever final. For every ill-conceived development that is knocked off, there is another one being hatched right now in the brain of a developer or government agency somewhere in Melbourne.

But for all the disappointments, there is also an abiding sense of achievement. As Christine Grayden notes in the introduction, “The other major trend in the history of conservation on Phillip Island has been the ‘greening’ of the island by PICS and Friends of the Koalas (FOK), Phillip Island Landcare, the many Coastcare groups and Phillip Island Nature Parks …

"Phillip Island now looks very different from the desolate landscape of the 1960s thanks to these groups and the thousands of volunteers who have helped in this greening project over the last 50 years. Many of the women in this book have been drivers in this greening, and will continue to do so.”

Copies of Women in Conservation on Phillip Island can be bought through the Phillip Island Conservation Society or by phoning Christine Grayden on 5956 8501.

What comes across in this inspiring collection of profiles is the selfless devotion of these women not to building private fortunes or well-paid careers but to nurturing and protecting “their place”, the remaining few wild places on Phillip Island.

There is no sense of sacrifice but immense satisfaction in protecting the island’s fragile environment, pride in the collective achievements, and pleasure in working with others for a worthwhile cause. For all the hundreds or thousands of hours of back-breaking work (physical and mental) they put in, these women invariably say they have gained more than they gave.

For the island’s environmental crusaders, there have been countless campaigns, many notable victories (the buyback of land on the ill-conceived Summerland estate, the campaign against a container port at Hastings, the establishment of a koala sanctuary, to name a few) and some disappointments, not least the Narre Warren-type housing estates now sprouting up around Cowes.

As the campaigners have learned, no victory is ever final. For every ill-conceived development that is knocked off, there is another one being hatched right now in the brain of a developer or government agency somewhere in Melbourne.

But for all the disappointments, there is also an abiding sense of achievement. As Christine Grayden notes in the introduction, “The other major trend in the history of conservation on Phillip Island has been the ‘greening’ of the island by PICS and Friends of the Koalas (FOK), Phillip Island Landcare, the many Coastcare groups and Phillip Island Nature Parks …

"Phillip Island now looks very different from the desolate landscape of the 1960s thanks to these groups and the thousands of volunteers who have helped in this greening project over the last 50 years. Many of the women in this book have been drivers in this greening, and will continue to do so.”

Copies of Women in Conservation on Phillip Island can be bought through the Phillip Island Conservation Society or by phoning Christine Grayden on 5956 8501.