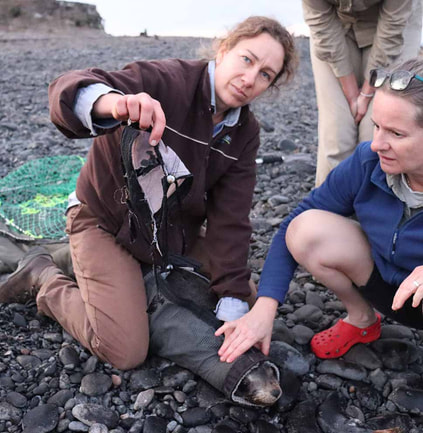

Marine scientist Rebecca McIntosh disentangles a seal pup on Seal Rocks.

Marine scientist Rebecca McIntosh disentangles a seal pup on Seal Rocks. By Lisa Gilbert

A LANDMARK study aims to save more Australian fur seals from entanglements by using thermal imaging technology on aerial drones to detect injured animals.

In what is believed to be a world first, the study, led by Monash University PhD student Adam Yaney-Keller and Phillip Island Nature Parks, is testing the ability of thermal imaging technology on drones to find entangled seals at Seal Rocks, off the coast of Phillip Island.

A LANDMARK study aims to save more Australian fur seals from entanglements by using thermal imaging technology on aerial drones to detect injured animals.

In what is believed to be a world first, the study, led by Monash University PhD student Adam Yaney-Keller and Phillip Island Nature Parks, is testing the ability of thermal imaging technology on drones to find entangled seals at Seal Rocks, off the coast of Phillip Island.

Seal Rocks is home to the country’s largest colony of Australian fur seals, with an estimated 19,000 seals and around 25% of the species population.

“We believe the practice of using aerial thermal imaging to identify entangled seals is a world first, and may be another tool to help save more Australian fur seals from serious injury or death,” Mr Yaney-Keller said.

“We believe the practice of using aerial thermal imaging to identify entangled seals is a world first, and may be another tool to help save more Australian fur seals from serious injury or death,” Mr Yaney-Keller said.

A drone camera identifies an entangled seal.

A drone camera identifies an entangled seal. Seal Rocks is an important breeding ground for Australian fur seals, and marine debris poses a significant threat to pups and juveniles, which can accidentally become entangled in marine debris due to their playful, curious behaviour.

“The seals are an indicator of the problem of plastic for all marine life. They live on land and at sea, so are an excellent research species for studying this issue compared to animals that are always at sea” Mr Yaney-Keller said.

“This project will help develop techniques to alleviate animal suffering and improve the welfare of seals, as well as revealing information about the long-term effects entanglements may have on the health and behaviour of individual seals.”

The project has been funded by Monash University, Phillip Island Nature Parks, WIRES, the Australian Wildlife Society, and Ecological Society of Australia through the Holsworth Wildlife Research Endowment.

As well as Seal Rocks, surveys have been conducted across Victoria at Gabo Island, The Skerries, and Marengo Reef.

The study also plans to track the behaviour of entangled seals once released to provide information of how they recover and develop after the stressful event, as well as whether their foraging and diving abilities may have been impacted.

The team will also monitor seal travel once released to determine marine plastic pollution ‘hot spots’, including where seal movements overlap with fishing activity and areas of plastic accumulation in Bass Strait.

“The seals are an indicator of the problem of plastic for all marine life. They live on land and at sea, so are an excellent research species for studying this issue compared to animals that are always at sea” Mr Yaney-Keller said.

“This project will help develop techniques to alleviate animal suffering and improve the welfare of seals, as well as revealing information about the long-term effects entanglements may have on the health and behaviour of individual seals.”

The project has been funded by Monash University, Phillip Island Nature Parks, WIRES, the Australian Wildlife Society, and Ecological Society of Australia through the Holsworth Wildlife Research Endowment.

As well as Seal Rocks, surveys have been conducted across Victoria at Gabo Island, The Skerries, and Marengo Reef.

The study also plans to track the behaviour of entangled seals once released to provide information of how they recover and develop after the stressful event, as well as whether their foraging and diving abilities may have been impacted.

The team will also monitor seal travel once released to determine marine plastic pollution ‘hot spots’, including where seal movements overlap with fishing activity and areas of plastic accumulation in Bass Strait.

“Wildlife entanglement in marine debris and plastic pollutants is a global conservation issue, which can cause starvation, infection, strangulation and can be fatal for seals. But we really don’t know the true scale of the problem or the long-term effects it may have on individuals and populations.”

On trips to Seal Rocks this year, Nature Parks teams have already detected three entangled seals, compared to last year when 16 were detected. On average, half of those seen are released.

Of those spotted in 2022, fishing equipment accounted for almost 70% of entanglements at Seal Rocks, with the majority involving recreational fishing line and hooks. Seals were also found trapped in hats, spearfishing rubber bands and plastic bags.

Drone surveys of the colony are currently done every two months using standard colour imaging and uploaded into the Nature Park’s SealSpotter website, where citizen scientists can count seals and find entanglements. But these colour imaging surveys likely under- detect hard to see entanglements, like those from transparent fishing lines that can look similar to rolls of skin of a healthy seal.

“Unlike coloured and bulky fishing nets, recreational fishing line entanglements are the most difficult to see, despite being the most common entanglement material, so we are likely under-reporting the issue. The injuries to seals can be extremely severe and cut deep into the neck over time as seals grow,” Mr Yaney-Keller said.

He said thermal imaging, which detects and displays surface temperature variations using infrared radiation, could help detect wounds and infections on entangled seals that may not be visible in colour photos alone.

On trips to Seal Rocks this year, Nature Parks teams have already detected three entangled seals, compared to last year when 16 were detected. On average, half of those seen are released.

Of those spotted in 2022, fishing equipment accounted for almost 70% of entanglements at Seal Rocks, with the majority involving recreational fishing line and hooks. Seals were also found trapped in hats, spearfishing rubber bands and plastic bags.

Drone surveys of the colony are currently done every two months using standard colour imaging and uploaded into the Nature Park’s SealSpotter website, where citizen scientists can count seals and find entanglements. But these colour imaging surveys likely under- detect hard to see entanglements, like those from transparent fishing lines that can look similar to rolls of skin of a healthy seal.

“Unlike coloured and bulky fishing nets, recreational fishing line entanglements are the most difficult to see, despite being the most common entanglement material, so we are likely under-reporting the issue. The injuries to seals can be extremely severe and cut deep into the neck over time as seals grow,” Mr Yaney-Keller said.

He said thermal imaging, which detects and displays surface temperature variations using infrared radiation, could help detect wounds and infections on entangled seals that may not be visible in colour photos alone.