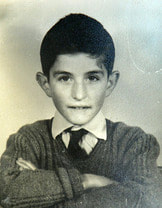

The author, aged 10

The author, aged 10 ON A grey, drizzly day in 1959, wearing a grey uniform, eager and apprehensive, I set off with my older sister Julie to walk the two kilometres to my first day at St Joseph’s Primary School. I was carrying my all-leather school bag, two shillings for the weekly school money tied in the corner of a hanky, a clean slate, and lead pencils. We also carried some eggs and tomatoes for the nuns.

St Joe's was a brand-new, cream-brick school building in the valley on the corner of Baillieu and McKenzie streets. Surrounded by a high cyclone fence and gates, topped with two rows of barbed wire, it looked like a low-security prison. The school had five rooms, all with composite classes. There were five rows of hardwood desks seating about 75 to 80 kids per room. The floor was bare hardwood and there was no heating in winter or cooling in summer, I don’t remember ever being cold or hot – there were too many other things to worry about.

The lower windows were frosted so our attention would not be distracted by the world outside. From inside all we could see was the tops of the gum trees and the water tower on the hill. The boys had to wear short pants to school even when there was ice on the puddles at 9am or jogging to 7am mass in winter. The short pants rule was our first sorrowful mystery.

In 1959, Wonthaggi had five Protestant churches and one Catholic one. The Mass in Latin was mysterious and magical. Catholics weren’t allowed to eat meat on Fridays or attend weddings or funerals in other churches. My father was once summoned by the priest after standing outside the Baptist church for the funeral of a fellow miner. Marrying out of your own religion could cause huge conflicts. Even the cemetery was divided into religious sections.

Italians were wops, wogs, reffos, dagos, spaghetti eaters and garlic-munchers. For some Aussies, the war wounds of lost loved ones were still raw. There was also a fear that Italians would undermine Australia’s standard of living. A local newspaper ran the headline “Influx of Italians - Wonthaggi Suffers”.

At the time, I didn’t know any of this. Ethnic and religious backgrounds weren’t issues among the assortment of agnostics, atheists, earthworms, unrepentant heathens, Samaritans, socialists and pagans in our neighbourhood on the south side of Wonthaggi. Most kids were free range. Big kids looked after little kids. They learned to negotiate a fair go by playing neighbourhood cricket on Strongs Reserve.

The Leggs next door shared their English Dandy comics with us. They were full of action scenes and characters doing amazing things. I pestered everybody about the words and their meaning and I was determined to learn how to read.

At St Joe’s, all the teachers were nuns, some kind, others old and grumpy, or violent and nasty. They were not like people but a separate species: three pieces of pale human looking down through the unknown scary darkness, their faces squeezed forward by stiff white material and covered in a thick brown habit with boots laced up above the ankles. It must have been hell in summer. At first sight of them, some kids cried. More than one had to be dragged kicking and screaming to their first class.

You could hear them coming up behind you because of the sounds their heavy boots made on the hardwood or by the jingling of jumbo-sized rosary beads. They had a crucifix tucked in a thick leather belt like a dagger, and no evidence of feet. One kid drew a picture of one with wheels underneath. They could hit you from behind with a stick, strap or yard ruler, pull you out of the desk by the ears or hair, dig their nails into your skin until you squirmed with pain, thump you between the shoulder blades, crack you on the knuckles with the edge of ruler or cane hard enough to draw blood. One even left a tattoo or two. Some of their faces had the look of suffering. Maybe they were only doing unto others what had been done unto them.

Nuns were effectively serfs. Their life was work, poverty, chastity and obedience. They were above parents, with a veto over the spelling of Christian names, but well below priests, who ruled by divine right and wielded extraordinary power in their parish. They could turn bread into God and their arrival at a school was greeted like that of a celebrity rock star. In exchange for obedience, they gave security to the vulnerable and unloved.

First thing in the morning and at the end of lunchtime, we lined up military style. To the strict, regimented, 120-paces-to-the-minute tempo of The Southern Command Band playing Our Director, we marched around the yard and into class. Like drill sergeants, the nuns kept an eye out for anyone out of step with the military music. If the marching wasn’t up to standard we went around twice.

Problem kids, some with a top-end glitch, sat in the front row. Smart girls sat at the back of the class and were mostly ignored. Some days they were sent outside to tutor some dunce. There was no grass in the playground, just white gravel and clay, and no asthma or peanut allergies but lots of blood noses, scraped knees and heads and the odd broken arm. No one was immune from a hit on the head.

St Joseph's School. Picture: State Library of Victoria

The little English I’d learned from our neighbours, the Leggs, Taylors and Colemans, was slow, measured and clear. On arrival at school, I could not understand what was going on and little of what was being said in the rapid, nasal gabble. I sat next to Dominic Cimino, fresh from Calabria, who, despite any English and total confusion, always wore a huge smile. Our parents’ dialects were so different that I could not understand him at all. We copied what everyone else was doing. It was a nightmare of trial and error, misunderstandings, yelling, deciphering unknown words. You knew not when you were about to offend. Some Anglos did not realise that shouting did not bridge the language barrier. Dominic was kept back a year and ended up dux of his year 12 class.

Our education was all about facts. We analysed sentences into nouns, verbs, adverbs, adjectives, participles, subordinate clauses and prepositions. We learned about vulgar fractions and we learned our times tables by chanting, word for word in tune. All you needed was a good memory and obedience. Answers were either right or wrong. You didn’t express your opinions or discuss anything. There was no need.

We learned the catechism by repetition. Religious instruction took up most of the morning. “Who made the world?” “God made the world.” We said lots of prayers and sang lots of hymns. We learned words like vocation, infallible, transubstantiation, scapula, indulgence, martyrdom, limbo, purgatory, original sin, mortal sin and sacrilege. Drinking water less than an hour before communion or eating less than three hours before was sacrilegious. Religion was based mainly on fear: fear of God, who controlled lightning, floods and drought, and fear of punishment, ridicule and disapproval from the nuns.

Original sin was the first bad news. We were born sinners and only religion could make us good. God had to send his only son to be tortured to death on a cross as reparation for our sins. Fear of hell (mentioned 16 times in the Bible) was not theological opinion but doctrinal fact. Souls burnt for all eternity in a fire many times hotter than any fire on earth. We were told horror stories of people who had committed a sin then died before getting to confession. Fear of devils and burning in hell gave some kids nightmares. You had to go to hell for mortal sins such as murder or missing Mass on Sunday. Venial sins such as lying and disobedience meant centuries in purgatory. Some believed that only two in 30,000 were going to make it to heaven. The pressure was on, and it put some kids off their lunch.

There was no library. Comics were banned and confiscated, which made them even more appealing. There was no Green Eggs and Ham, just the John and Betty school readers of the time. In grade 3, the school reader arrived half way through the year, and that was it, apart from the school paper, which arrived once a month and could be read in 10 minutes. It wasn’t until grade 6 when Sister Angela, the head nun, read us chapters from the books Bush Holiday and Bush Christmas, that I was read something pleasurable – for half an hour after lunch my mind could wander in a more relaxed place.

We learned to write numbers and letters by scratching on a piece of slate, the same material used by our cave-dwelling ancestors. Everybody had to hold a pencil or pen in exactly the same way, and always in the right hand. We had to use messy ink pens and blotting paper. Getting ink from the inkwell to where you had left off writing was tricky. Nibs broke, got caught on the paper and splattered ink on everything, including Kim Williamson’s ponytail. You couldn’t correct a mistake.

The Coldebella intellect has always been slow out of the blocks. No Coldebella had ever distinguished themselves in academic achievement and I wasn’t about to break a long family tradition. One of my school reports had me placed 37th in the class.

Class tests were stressful. The best results were displayed on the back wall with a gold star. The worst were also displayed, with “Poor” stamped on them. Dunces were ridiculed and humiliated in front of the whole room then had to stand in the corner. Some of them were newly arrived migrants who did not speak English at home and whose parents were too busy working seven days a week to pay off their fares to take much interest in education. Some children arrived at school without books or pencils. John Gheller was expelled from school but reinstated after his father agreed with the priest to supply bags of peas and potatoes to the church.

Guilio Marcolongo and I still suffer from post-Catholic stress disorder in front of an audience or when trying to concentrate while someone is watched. The memory of humiliation or a whack can be mentally paralysing.

Part II: Suffer the little children

THE Bible says, “Spare the rod and spoil the child” and nobody wanted a spoilt child. With up to 80 kids to a room, the nuns needed to reassert order constantly. They did not spare the rod, strap, cane or yard ruler. Only violent physical punishment, humiliation and ridicule would fix a naughty child.

You could get the cuts for being late for school, talking in class, speaking in Italian, being out of your desk, not knowing an answer, giving an incorrect answer (it was safer to put your hand up even if you did not know the answer), writing with your left hand (the work of the devil), biting your nails, making a mistake, not knowing the times tables, messy work, having an untidy desk, banging your desk lid, daydreaming (the only escape from the infinite boredom), dropping marbles in class (no escape with a hardwood floor), passing notes in class, asking a wrong question (“How do we know we have a soul?”), offering a different opinion (referred to as contradicting) and touching girls or their hair.

One kid was belted until he shit his pants. There was a tin of sawdust in the corner for such events. I saw Pat Connelly get the strap for pulling up his socks in class. “You’re supposed to get dressed at home,” Sister Maureen told him.

I walked Adriana to school in her first days. She was two grades below me. Like many Italian kids, she started school with no English at all. One day she was belted till she vomited. She went on to become a lecturer at Monash University.

With few exceptions, parents accepted the school’s authority. After all, if a child lacked courage, he or she could not make it through what was believed to be a difficult and dangerous world. You weren’t supposed to cry. A kid who did was mocked for being a cry baby. At his first strapping, another kid started crying before he got hit and stopped after he had been. Everyone in the audience thought it was hilarious, except him.

The Catholic Church believed suffering was redemptive. The more you suffered here on earth, the less time you would do in purgatory. Had not Jesus suffered and died on the cross for our sins? In case anyone forgot it, a statue of his near-dead, tortured body hung in the centre of the room above the blackboard.

You could sin through thought, word and deed. If you thought “Shit!” when you got the cuts, you had to confess that to the priest. He would sit in the confessional, head bowed forward, his thumb and forefinger on the sides of his forehead as though he had the father of all headaches. It was miserable to struggle with the evidence that you were not the person you should be and that it was making your parents and teachers unhappy and angry. My school photo at this time shows me looking beaten, trapped, miserable and alone.

“Suffer the children to come unto me” was a bad choice of words, especially for the ones not blessed with status, talent or good parenting. If you were poorly clothed, wore glasses, had puppy fat, had red hair or had a stutter, you were probably bullied. It was safer to be a silent bystander than to intervene. The big problem with cruelty is that it is learned, absorbed into the culture and passed on to those further down the hierarchy.

My strategy was to try to keep a low profile by reducing my visible presence to a minimum, keeping behind the kid sitting in front. Mark Pellizer’s was to cover up like a boxer on the ropes waiting for the bell. It was all stick and no carrot. The use of cruel, violent punishment in Catholic schools should be added to its list of sorrowful mysteries when they do the Stations of the Cross.

The first time I got the strap was when a mob of us kids crossed McKenzie Street one playtime to watch a bulldozer constructing the fire brigade running track. By grade 4 I was used to the strap. Try as I did, I don’t think I went a week without it. I don’t think Fatty Storti went a day without it.

One day the nun had sat me next to a new girl, Valmay, a beautiful, doe-eyed blonde with skin like milk and a face like a saint. She could have been the inspiration for Manfred Man’s Pretty Flamingo. Even her hands were beautiful. She came on the bus from a small fishing village called San Remo, way out of town. We weren’t allowed to talk but such was her presence I would not have known what to say anyway.

A nun did an inquisition every Monday morning, asking the class who had missed Mass on Sunday. One morning Val put her hand up. I was shocked. I couldn’t imagine her doing anything sinful. Why? She explained that her parents hadn’t taken her and the nearest church was far away. The nun said she should have got her parents to take her to church and told her to hold out her hand. Tears filled Val’s eyes. She hadn’t had the strap before. The room was silent. I was terrified when I saw how she was holding her small limp hand, its whiteness radiant against the blackboard with its heading A M D G.

The next thing I remember Val was back in our desk, her forehead on the desk lid, her red burning hands curled upwards, twitching beside her. There was barely a sound, just faint sobbing and gasping as two lines of tears ran down the desk lid and formed a wet patch on her dress. She cried for what seemed like a long time. I couldn’t say anything to her and I couldn’t touch her. I could not show any emotion. We were expected to suffer pain and disappointment in silence. She didn’t come to school the next day.

Next week it happened again. She knew that silence was safety, that lying was the best strategy. I tried showing her how to hold her hand to lessen the pain but she just accepted God’s punishment. Children feel other's pain as if it is their own and it was painful to watch.

Like many people after six days of work, her parents didn’t want to go to Mass on Sunday to hear that the world was full of sin and evil. At our Mass, Father William O'Regan harangued, exhorted, pleaded and commanded. He would go into loud, angry, red-faced, saliva-spraying rants against the pill, mixed marriages and Commos. The editor of the local paper, Tom Gannon, was the only one brave enough to walk out. Father O’Regan was a big advocate for the Vietnam War. Girls wearing bikinis was sinful, as was girls playing footy. Even going to other churches for weddings or funerals was not allowed. Some came out of church feeling berated, dispirited and confused.

Father O’Regan told his congregation not to have anything to do with Joe Chambers, a teacher at Billson Street Primary. Joe, an agnostic with Christian values, questioned out-dated ideas and proposed many new ones. To Father O’Regan “different” meant bad or evil. In reality, Joe and his clan were always leading the way and at the heart of every progressive thing that happened in the town. He taught English to Italians, learned some of their songs, did their paperwork, treated all us wog kids as equals. Italians only knew them by their works not their politics. To the Italians, Joe was bravo bravisimo.

Later on I joined the choir. Practice was really strict but it got you out of class. We only ever sang in church. Father O’Regan was choirmaster. He caught me unaware once with an open-hander square on the ear. Not long after that I got a trip by train to see an ear specialist at the Eye and Ear Hospital in Melbourne. I don’t know if he was the cause but I know for sure it wasn’t a non-Catholic. A delegation of parents had been to the school to express their concerns about their children’s ear problems To this day, a male Irish accent sets my teeth on edge.

Part III: The agony and the ecstasy

IN 1964 the US started bombing Vietnam. Conscription was reintroduced in Australia. A black terrorist called Nelson Mandela was jailed for life. Bob Dylan released Masters of War. The Beatles came to Melbourne. Teenagers started to twist and shout. And a skinny Aussie kid nicknamed Midget became world surfing champ. For us kids, it was the first time a male had been seen doing something graceful and beautiful instead of tough and hard.

As Bob Dylan had predicted, the times they were a-changing although we didn’t realise it at the time. In 1964 our school reader had the story of General Gordon and Simpson and his donkey and we had Sister Benitsi, who was old, bitter, sarcastic and mean. Although waning in physical strength, she could still strap the back of Frank Angarane’s legs with memorable effect.

She may have been traumatised during the Anglo-Aboriginal wars because she told both my class and my brother’s “Never trust a blackfeller behind your back”.

One poem we had to memorise was The Pioneers, which had the line, “We fought with the blacks and we blazed the tracks that ye might inherit the land”. Our school reader had a story about a narrow escape from blacks with "savage faces", "wild glaring eyes" and "fiendish expressions".

Some kids were terrified of Aborigines. I wasn’t. All the ones I met were pacifists despite what they had to endure. A very dark-skinned Daryl Cuddy, who lived in Merrin Crescent, was a meek yet wizard explorer who led expeditions to distant swamps and unknown bushland. We shared many a bush-to-beach dreaming afternoon of escape. Another old neighbour was Nigger Undy, who believed snakes were not evil and dangerous but shy and timid creatures worthy of respect.

We were also told horror stories that gave us a morbid fear of evil, godless Communists. One kid in my year made it to year 10 thinking people in Russia did not own their own pants. The DLP warned us there was no place on earth that could not be reached by Russian missiles or the atomic bomb. The campaign for a national health scheme was believed to be the bait in a trap to enslave us all.

For some Catholic kids, hurling stones and abuse at the state kids was a centuries-old tradition, a way of venting built-up stress and fear. It was more sport and entertainment than malice – taunting one another’s inaccuracies and learning the eye-foot skills to duck and sidestep the few stones that were on target.

Most of Wonthaggi’s roads were red stone so there was an endless supply of all sizes. Walking to and from school could be an adventure, depending on the route and the company. There was a track though the bushland between Reed Crescent and McKenzie Street. In our early years, we walked mainly via the back lanes avoiding the state kids in unknown territory. June McRae (nee Priestly), who grew up in Merrin Crescent and went to Billson Street School, once told me that in her day Catholics heading along Hagelthorn Street fought state school kids heading down Billson Street, turning the intersection into a war zone.

At school, we played skippy, jacks, hoppy, chasey, rounders, kick the tin, British bulldog (until the nuns banned it), piggyback fighting (also banned), brandy, rock, paper or scissors and marbles (square, tracker, bunny holes and footy). In marbles Peter Campagnolo had the eye-hand co-ordination and precision of William Tell.

Kids were tough and took risks. They wore a plaster cast or a large scab like a badge of honour and achievement. One lunchtime, while playing in the lane next to the school, I collided with the handlebars of a bike. It cut through my eyebrow and would not stop bleeding so the nun got Mose Tiziani to dink me home on his bike. It was a job to hang on. All I could see was the handlebars and front wheel. When we got home my mum told Mo to dink me to the hospital. Mo was so glad to be out of school he would have dinked me to Dandenong rather than go back to class. He hung around until they stitched me up then dinked me home.

Time moved very slowly. Without a break, the afternoons dragged and crawled. The unending, relentless repetition, boredom and repression of school sometimes put us into a coma of daydreaming. It was a temporary escape but if you got caught it was out the front to get the cuts.

Noel Winslett tried escaping into the bush across the road but a nun sent Gerard McRae to capture him. Just like in a movie he was captured and brought back to face his punishment.

One lunchtime, Peter Suckling was so desperate he asked me to push him into a deep puddle. It worked. Wet through, he was sent home, where it was just his dad, the tools and a jigsaw of car parts. The cough, shudder and glorious hymn of a dead engine coming back to life was heaven for Peter.

Debbie Dunlop, finding her escape route blocked, just climbed on a desk and got out the window. Kevin Hill pioneered the four-day week. For a few months in grade 4, he helped his father at work on Thursdays by driving a truck.

A few years earlier, kids like Vic Bertacco and Frank Loughnan escaped school permanently and went to work at the age of 13. Frank’s parents thought he was still going to school. Danny Luna and Tillio Bottegal continued their AWOL recreation pursuits into secondary school.

Boredom shrank some brains. In others the pressure led to frustration, risk-taking, anger and violence. With no affection or evidence that they were loved, some started to accept themselves as being bad and unworthy, possibly cursed with the devil inside. Minds locked in anger can’t learn, let alone thrive. There was no space for discussion or tolerance of daydream believers or escapees.

We were lucky to have Rod McRae in our grade. At age 10, he was a smiley, cheeky, feisty, creative, left-handed rascal with an infectious laugh. He led from the front, whether it was getting a ball, climbing a tree, dodging a whack, eating Italian food or taking on big bullies. His was not the direct confrontational approach; his tools were imagination, wit, oratory and charm. He could conjure fun out of the ugliest situation. To us wogs he was the Messiah. He did not deliver us from evil but he could puncture any over-inflated ego or ridiculous situation with a repertoire of quick commentary, irreverence, crazy laughs and endless stupid faces. Once out in the yard he even made a nun smile!

His talents and cleverness had no place in the curriculum or regimented teaching style. His imagination could not be stifled or destroyed. The nun sat him all over the room to neutralise him. When he sat next to me my boredom ceased. When fun and laughter are suppressed for long enough it can explode on the most trivial spark. Rod could always make that spark. When I walked back to my seat after a strap, I couldn’t look at him because I knew he would have one of his comic expressions and that it would crack me up.

With Rod, tears of pain mixed with the tears of laughter. Ecstasy in agony, never boredom. It was a relief when his antics eventually got him sat out the front with Frank Marotta, Renato Battilana, Noel Winslett and John Legione. They all had difficulty being submissive and silent and exhibited what today might be described as challenging behaviour. The four of them teased one another or wrestled – anything to break the boredom and monotony. It was like the Three Stooges meeting the Marx Brothers. The nun strapped them and they treated it as part of the game, an opportunity to entertain the class by faking cries of pain. Pulling their hands away got them more, especially if the nun hit her leg. The class watched enthralled at the theatrics, each whack bringing forth a low chorus from the audience of sucked-in breath and low “Oooohs” and “Ahhhhhs”. If you got caught laughing you got strapped too.

Renato was fresh from Italy. His English wasn’t good but after one marathon strapping session he displayed his mental arithmetic skill by pointing out, “Franco he gotta one amora thana me”. We in the audience went hysterical.

These four masters of pain turned getting the strap into an undeclared contest. Alan Storti kept a tally on a wooden ruler. They experimented over the years with various hand and arm techniques for different nuns, first to avoid pain but later for sound effects. They realised that the louder the clap on the hand, the more the audience responded. Noel Winslett was not blessed with the gift of faith so got countless straps. After years of experimenting, he discovered that if you held your hand in the shape of a cup, the cushion of trapped air gave out plenty of bang and saved some pain.

One day the right combination of error, anger, strength, speed, distance, angle and sheer brute force all came together with leather on skin at the exact point on Frank Marotta’s perfectly cupped hand. The bang that followed made one kid near the front put his hands to his ears. Another kid thought he saw the Holy Ghost but it was just chalk dust sliding down the blackboard. A flock of birds took off from a tree across the road. Kids in the next room stopped and looked around thinking a firecracker had gone off. Frank Marotta, looking canonised or transfigured, smiled like Pavarotti at his dumb-founded audience who could not believe their ears. It was my best day at St Joe’s!

Part IV: Soldiers of God

THE Jesuits said “Give me the child until he is seven and I will show you the man ”. As the twig is bent, so grows the tree, but not all twigs are the same. Some snapped early. By grade 6, some kids were so demoralised that they had come to accept that they were bad and gave up seeking approval. From their teens, they became defensive, sullen and defiant, A few were so angry they could not communicate feelings or emotions. For some, the first time they drank alcohol was the first time they felt good about themselves.

Eddie, a slow learner, was near the bottom of God’s creation and really copped it at St Joe’s. With an abusive parent who drank, poorly fed and clothed and with no sporting skill, he was despised and humiliated by his teachers and classmates. One nun set the class bully onto him. He was persecuted on his way to and from school. Walking with a hounded, hunched, oppressed gait, he never fought back. His life was hell. The last I heard he was in jail.

When I hear Bob Dylan's The Chimes of Freedom, I think of all the Eddies, Smithies, Maccas and Tommoes of that era who went almost straight from school to jail. They could no more help going to jail than we could help being outside.

Fighting was a way of settling differences, a formal or informal sport and something to celebrate after a few beers or when you could not contain your anger and frustration any longer. You sometimes had to fight to maintain status. Violence was not a problem to be solved but a contest to be won. The police youth club and some dads coached their boys in boxing; others just learned by example. Attilio Moresco made a boxing ring in the back yard to train his boys for what he believed was a hostile world

A poem in our grade 6 reader went:

What can a little chap do?

He can fight like a knight

For the truth and the right

He can fight the great fight

He can do with his might

What is good in God’s sight.

In 1992, George Kiely laughed when I said St Joe’s was tough. He told me he and his brother came from Tassie to St Joe’s in grade 4. On his first day he had three fights lined up by lunchtime and his brother went on to be welterweight champion of Australia.

When I was in grade 6 our bishop came to Wonthaggi for our confirmation and we all lined up to kiss his ring. He told us we were “soldiers of God enrolled in the army for all time”. One of my favourite hymns at the time was Faith of Our Fathers, which had the lines “How sweet would be our children’s fate if they like men would die for thee” and “We will be true to thee till death”. We were told that to die fighting Communists in Vietnam gained us martyrdom, which meant a short cut straight to heaven without doing time in purgatory. Mechanical obedience to orders made school like a cross between a religious cult and a military camp. I don’t know what more you could have done, apart from gun practice, to prepare soldiers for war.

We were told our church was the one true church and not to play with the state kids. We got the impression that we were God’s chosen people and they weren’t. I felt a sense of privileged status knowing I belonged to “the one true holy church”. One nun told us not to stand up when God Save the Queen was played before films at the Union Theatre but my mother insisted that I did. At no point during this time did I realise that all the physical violence I suffered in my life was coming from Catholics and the only non-Italians giving us a lift when it rained were parents from the Billson Street state school.

After a day of hearing and reading in our Catholic history reader about the evil torture and murders perpetrated against us godly Catholics by our evil enemies, I sighted Phil Grinham ambling home from Billson Street School as though there was nothing at all wrong with the world. He must have seen my seething, fuming, self-righteous glare and ran for home down Edgar Street. I chased, scooped up a stone and hurled it as hard and high as I could in his direction and waited and watched as the descending stone gathered speed. Phil was running flat out and leaping the drain outside his house when, to my shock and horror, the stone hit his head. Phil went sideways with the impact but he kept his footing.

It wasn’t what I’d expected and I felt bad. For days I expected revenge attacks but none came. For some time, younger kids like the Blundells ran when they saw me or my brothers. Word must have got around that I was dangerous and to be avoided.

In grade 6, the parents were under pressure to give their boys a proper values-based education by sending them to what sounded like prestigious secondary schools run by Christian Brothers. The alternative was Wonthaggi tech high – now the secondary college – across the road. We were warned some of the teachers there believed we evolved from monkeys.

On my last day at St Joe’s, some of the boys who were going to the Christian Brothers threw buckets of water over Kevin Hill and me. And that was it. Jesus had said “Feed my sheep” but our school diet had been Spartan. Wet and slightly unbaptised, leaving my school report behind, Kevin and I climbed up the cliff, under the cyclone fence topped with barbed wire and out of the valley of tears, up the Merrin Crescent lane towards home. All through primary school, Kevin’s house was the only non-Italian Catholic house I had been inside.

At the tech high, I ended up in the same year 8 class as Phil Grinham. We both kept pigeons and would take them out on the Harmers Road on our bikes and watch with pride, joy and a little envy their soaring and curving, meandering flight home. Some would stop flying and playfully tumble through the air on the descent to the loft, landing on their feet at the last instant. Occasionally we surfed together, enjoying a similar exuberance and release. I was always too embarrassed to mention the rock.

At the tech high, we found that some of the boys who came from St Paul’s home in Newhaven were even more abused than us Catholics.

Slowly I learned that difference of opinion does not make the other person wrong. and that we could all be as one without being the same. It was a joyous discovery that there was not just one good Samaritan, that the world was full of them. We were still not as good as we could be but not as bad as had been made out. I found wisdom, humility, respect and kindness were abundant, with many non-religious people living abundant, fulfilled and balanced lives. Without being aware of it, my faith in religion was starting to erode.

In 2010 I saw Phil Grinham sitting alone near the mine whistle in Apex Park. I sat down and after a while asked if he remembered the stone. Without changing his look or tone, he slowly rubbed the top of his head and said he could still feel the lump.

That was all he said. With no religiosity, how do some people know that to turn the other cheek is the best first strategy in conflicts? This is a truly glorious mystery.

COMMENTS

December 5, 2012

I can't accept that there will only be one more 'instalment' to read! Frank, you can't do this to us!! Truly, you are to be applauded for this grand effort. You have a wonderful gift and I sincerely hope that you will entertain us with many more stories. Thank you for the sheer enjoyment of it all.

Vilya Congreave

December 4, 2012

Congratulations to Frank Coldebella on such an insightful factual writing style about school days with the Josephites. Went through the same at St Lawence's Leongatha, not as bad though. Love the humour - keep up the good work. I wonder what Mary MacKillop would have made of it all ... it certainly was not what she had in mind. Viva Belluno.

Bianca and Nadia Stefani

December 2, 2012

Absolutely loving Frank Coldebella's memoirs of childhood at St Joe's. Change the name to St Mary's or any other Catholic primary school in the '60s and the stories are much the same.

Thank you for bringing back so many childhood memories, some good, some bad but all forces that shaped many lives, including mine. I would not be the strong woman I am today if not for the experiences in my formative years. Secondary school was just as memorable but more enlightening as I was taught by the same forward-thinking and emancipated nuns who taught Germaine Greer.

Now I am looking forward to Frank's next instalment.

Janice Orchard

November 28, 2012

I've loved reading Frank Coldebella's memoir. Sadly, much of it would reflect the experience of many educated in Catholic schools at that time.

Alba Del Bianco

November 23, 2012

I, like Frank Coldebella, went to St Joe’s Primary School (what feels like a million years ago). His vivid descriptions have brought the memories flooding back. That white dusty playground that seemed to be bursting at the seams with children. The only thing missing (which may well be included later on) was the small milk (often warm due to standing in the sun) that we were forced to drink! No thoughts of lactose intolerance in those days.

I look forward to the subsequent parts of this story. Well done Frank and Bass Coast Post. Keep up the great articles.

Adriana Tiziani

February 21, 2014

Thanks Frank, just read your experiences as a student at St Joe's Wonthaggi. It brought so many memories back to me as I spent the same years at St. Joseph's at Kooweerup. Its building, behaviour of the teachers, the education, the physical abuse of minors, the sparse play ground were all the same. It was horrible and it has taken a lifetime to get over it.

It is no wonder that something like 97 per cent of students who went through a Catholic education gave the religion away. It was a terrible system.

Pee Bee