When I was growing up, Wonthaggi made a lot of stuff. We manufactured agricultural machinery and clothing. The people who came from Melbourne had their Levis and famous brands but we had our own stuff that was made right here in the town. Shirts and windcheaters were made at Exacto, now the Plaza Arcade. Pants and jackets were made at the Aywon factory on the corner of McBride Avenue and Watt Street. That’s where my mother and a lot of other mothers worked.

You could always get a job in the holidays if you wanted one. In December 1968 our neighbour in Reed Crescent, Andre Van der Craats, got me a holiday job at the Country Style Bakery where he worked, and for the next four years of school holidays I got an education in life.

Everyone from those places kept their jobs if they wanted them. Even the delivery horse, Tommy, from the Co-op kept its round at South Wonthaggi and shared a paddock with “Chick” Hanley’s milk delivery horse in McKenzie Street. It also kept down the grass on some vacant lots.

Butch Lamers was the foreman at the new bakery. Andre Van der Craats, Jim Burns, David Oldaker and Graham Hamilton worked under him and shared the various jobs such as greasing tins, rolling dough and placing it in the tins in the ovens, removing hot tins from the ovens, and then starting all over again with the next batch.

“Curley” Gardiner and “Pump” Motherwell delivered the 150 pound [68kg] bags of flour and other ingredients from the railway station goods shed. The flour was pulled to the top floor by pulley then Curley would climb the stairs and carry the bags on his back to a stack in the corner.

Danny Luna and Bill Dunbar would start as early as 2am. Danny remembers carrying boxes of yeast, peel, sultanas, gluten, and other ingredients from the storeroom behind the office, across the carpark and up the steep unlit steps to where they would be mixed. Danny would also mix the batches of dough which would then be tipped down a chute where Bill would cut them into various weights with a special machine before each was then hand rolled and put into tins waiting to rise before they were baked.

Once out of the ovens, and during hot weather, the racks of loaves were wheeled out to the verandah to cool. Sometimes, a family of sparrows ate the corner off a loaf. It was then that Sandy Dunbar, Bill’s dad, and I worked together operating the machine that sliced the loaves and heat-sealed them in wax paper, which we then put in crates for the carters. It was a continuous round of slicing and stacking.

Bread carters Maurice Cengia, left, and Moose Boynes at the former Country Style bakery in Wonthaggi, photographed shortly before it was demolished in 2003.

Bread carters Maurice Cengia, left, and Moose Boynes at the former Country Style bakery in Wonthaggi, photographed shortly before it was demolished in 2003. The crusty loaves were called “Dagoes”. There was no malice in the name, just that a crusty loaf was what most Italians preferred. The name came about because one of the bread carters, who delivered loaves to Kilcunda, referred to the Bass Highway where it dipped near Mabilia Road as Dago Dip. Lots of Italians who worked at Mabilia’s Coal Mine lived there. Thus, lots of crusty bread was delivered there.

In those days, anybody could legally camp anywhere on coastal public land, and so, in peak summer, Frank Coleman delivered more bread to the campers at Flat Rocks than to Inverloch. When the new bridge to Phillip Island opened in 1971, more Melbourne people headed for the coast. Surfboards were smaller and more affordable and from Christmas to Easter we worked till late.

During busy periods, the smell of freshly baked bread wafted down the lane into Graham Street where Jungle and Keitha Sloan and his four kids would make us the best sandwiches. I also did errands to Frank Coleman’s takeaway, opposite the one-stop-shop.

Sandy Dunbar, who I mostly worked with, was a crusty old retired Scottish-born coalminer. When I knew him, the years at the coalface were deeply etched in his face and hands and made him look much older than he actually was.

When I got to work at 6pm, I went to the bin of discarded broken baked loaves. The still-warm crusts were just the thing after a day at the beach. Sandy, perhaps echoing his grandfather’s voice, would always say quietly, “Are you hungry, son?” He was from the generation who lived through the “real poverty” of pre-World War I Britain and was concerned I never had enough to eat.

One night, before heading home, I told him I was going to ride my bike to the Oaks where “Bags” Legg was staying in the Beckerlegs’ hut. Sandy knew that the fish didn’t always bite and went into a state, making sure I had the max of day-old bread I could carry. I don’t know if it was so I would catch more fish or so I wouldn’t starve if I didn’t catch any.

On our break from slicing and wrapping the cooled loaves, Sandy and I would sit on crates under the verandah which faced the old post office, where, upstairs, a team of women manually connected phone calls and gave Bobby Dunstan telegrams that he delivered all over town on a solid steel single geared red bicycle. Laurie Chizonetti would wave as he drove home up the lane from his fruit shop in McBride Avenue in an EH station-wagon full of family and staff. We waved back.

Sandy would pull out a battered shining tobacco tin and do the meditative ritual of rolling a cigarette, peering over his wire rimmed spectacles as he gathered his thoughts. “Whatever you do, son, don’t smoke,” he would say, the gnarled and scarred thumbs and fingers moving slowly backwards and forwards together making a perfectly formed cigarette.

He would go on to explain the evils of smoking by using the arithmetic of money over decades. To the son of an unemployed coalminer, as I was then, it amounted to a fortune.

He would put the cigarette to his mouth, light it and draw in the smoke. The coal at the lit end would glow. Then he would start teaching me his wisdom. It was on these breaks where my real education occurred.

Sandy grew-up in an extended god-fearing, coal mining family in Aberdeen not far from where other Wonthaggi families, like the Chambers, also came from. He was two years old in 1903 when his father died, and he was twelve years old when he won a scholarship that meant he could continue on in school and be the first in his family out of pits into educated prosperity. However, a year later the beginning of the First World War robbed him of that ambition. The enthusiasm, music, fanfare and propaganda made it seem as though the war was the answer to Britain’s problems, but the reality was that along with millions of others, the war robbed Sandy of opportunity, hope and belief.

Completely disillusioned, he decided to leave Scotland in search of change in sunny Australia. He followed other Aberdeen families to Wonthaggi. He was 21 years old and married when he was hired to work in the State Coal Mine on 16 December 1922. He worked there for 40 years until he retired in 1962.

By the time I got to know him, Sandy had accumulated a lifetime of wisdom and I listened to every word he said. I was still an obedient Catholic boy, but life’s lessons had turned Sandy into an in-your-face socialist. No polite carefully worded questioning of beliefs from him. His verbal barrages against the ongoing war in Vietnam, the theft of corporations and banks, the “illogical, superstitious, nonsensical religions” usually started with an exasperated howl of “God suffering Christ!”

Then he would go on: “There’s always money for war, Son.”

“Heaven is a bribe and Hell is a threat!”

Sandy knew all the weird and rude verses in the Old Testament: “So, who did Cain marry?” he asked.

“You can cure the sick and blind, feed the hungry, turn water into wine, but if you upset the money lenders in this world, you’ll be dead by Easter!” he proclaimed.

By the end of summer my faith in Catholicism was looking rickety.

Sometimes, other casual summer workers like me would join our conversations. Sandy had quiet, earnest discussions with David Mitchelmore, a student, and another worker, a Vietnam conscript on leave, about the obvious difference between defending your country and attacking someone else’s.

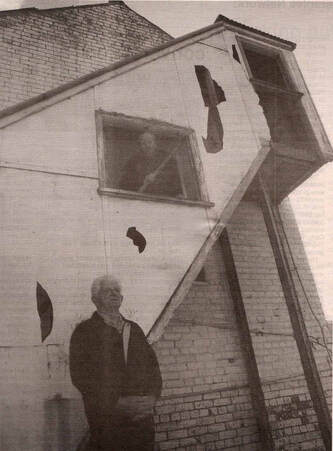

The back of Country Style Bakery looking up Abrahams Lane towards the old post office on Watts Street.

The back of Country Style Bakery looking up Abrahams Lane towards the old post office on Watts Street. Harry and Sandy always got things going long enough to finish the shift. Once, with a genius of teamwork, the repair was made with a bent wire and piece of beer can. The next day, someone from Danny Carrs would do the permanent repairs.

Harry was gay, which was illegal at that time. His remains were found burnt in a Melbourne park. The police report said it was suicide. No one from Wonthaggi who knew him believed it.

In early ‘72 I left the bakehouse to work full time at Coldon Homes. Not long after I left, the bakery was sold to Home Pride. Economy of scale continued its march.

It was a great job to have in what today would be called hard times.

This essay was first published in The Plod, the newsletter of the Wonthaggi and District Historical Society.