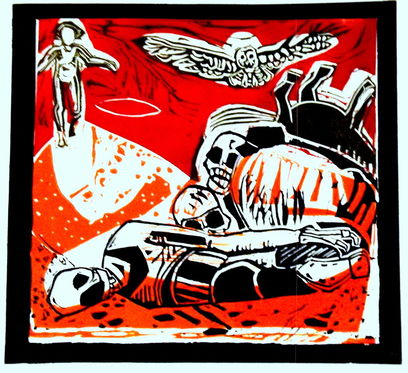

Cartoon by Natasha Williams-Novak

Cartoon by Natasha Williams-Novak "Australia is not a country that goes looking for trouble,” Tony Abbott said recently, but our history tells a different story.

By Frank Coldebella

ON WINNING the Americas Cup in 1983, Alan Bond described it as the greatest victory since Gallipoli. How did a disastrous failed invasion of a Muslim country that posed no threat to Australia come to be the symbol not just of victory but of our nationhood?

The first casualty in war is the truth and the untruth often lies in the things that are not reported. Some things don’t seem important at the time; others are deleted to make our history look better.

“Australia is not a country that goes looking for trouble,” our Prime Minister, Tony Abbott, recently stated. Our history tells a different story.

In 1899 cheering crowds, patriotic music and the prayers of clergymen saw off 1200 men to the Boer War.

In 1900, more went to fight the Chinese in China. Henry Lawson wrote to the Bulletin: “Some of us are willing – wilfully, blindly eager mad – to cross the sea and shoot men whom we never saw and whose quarrel we do not and cannot understand”.

In 1908 the Australian government introduced compulsory night and weekend military training for males aged 12-26. When war was declared in 1914, Australia had a well-trained, disciplined army itching for a fight.

On seeing a group of soldiers leaving Melbourne to fight, a Mrs Massey wrote: “I think I never saw a more joyous party. They reminded me of happy school boys bound for some party of pleasure ...”

According to the Argus newspaper, “Victoria was thrilled to the core” when war was declared. There was “overwhelming excitement and jubilation”. The same day a patriotic mob in Melbourne attacked the German club and Chinese quarters in little Bourke Street, smashing windows, looting property and terrorising the inhabitants.

In poor country towns, the news of war inspired parades, pledges of loyalty, concerts, patriotic funds and the ringing of church bells. Farmers donated horses and bullocks. The atmosphere, according to John McQuilton, was “almost festive”.

“The freest and best country on god’s earth calls to her sons for aid,” Prime Minister Billy Hughes stated. “Destiny has given you a great opportunity.”

Cartoon by Natasha Williams-Novak

Powlett Express

In 1908 the Australian government introduced compulsory night and weekend military training for males aged 12-26. When war was declared in 1914, Australia had a well-trained, disciplined army itching for a fight.

On seeing a group of soldiers leaving Melbourne to fight, a Mrs Massey wrote: “I think I never saw a more joyous party. They reminded me of happy school boys bound for some party of pleasure ...”

According to the Argus newspaper, “Victoria was thrilled to the core” when war was declared. There was “overwhelming excitement and jubilation”. The same day a patriotic mob in Melbourne attacked the German club and Chinese quarters in little Bourke Street, smashing windows, looting property and terrorising the inhabitants.

In poor country towns, the news of war inspired parades, pledges of loyalty, concerts, patriotic funds and the ringing of church bells. Farmers donated horses and bullocks. The atmosphere, according to John McQuilton, was “almost festive”.

“The freest and best country on god’s earth calls to her sons for aid,” Prime Minister Billy Hughes stated. “Destiny has given you a great opportunity.”

The Railways refused to employ single men because “single men should be at the front”.

In September, 1914, the Australian Government introduced censorship of press and mail. The War Precautions Act had wide powers against all opponents of war. The sale of anti-war papers was prohibited.

In the newspapers, the war was referred to as “the big game” and “the greatest sport of all”. It promised volunteers travel, action and adventure, then home by Christmas. A common fear among volunteers was that the fighting would be over before they got there.

In 1915 C.J. Dennis wrote: “What’s just plain stoush with us right here today is valour if you’re far enough away”.

“THE SPIRITS OF YOUR DEAD PALS CALL OUT,” shouted an enlistment poster. “WE HAVE GIVEN ALL. ARE YOU GOING TO BETRAY US?”

The Miners Union told its members to ignore the recruitment ads. “War increases the misery of the poor,” the union stated. The “blood-spilling business” only enriches a few.

Protestant churches passed resolutions in favour of war. An Anglican preacher told his congregation: “Christ submitted himself to the conscription of heaven. He came to obey and carry out the act of death imposed upon him … Christians must therefore vote for conscription.”

In a collection of interviews with First World War veterans published in 1972*, a South Gippsland returned soldier said he sought the advice of his local minister before enlisting. “He convinced me that the war would end all wars and that it was right to go …”

It was a difficult time for those who wanted to obey Jesus’s command to “Love your enemies”. In some country towns, pleas for peace and sanity became acts of treason opponents to conscription were tarred and feathered. In Melbourne soldiers disrupted a peace meeting during a speech by Vida Goldstein. The Prime Minister called anti-conscriptionists “vipers, cowards, dirty dogs and parasites”.

Casualty lists disguised the real number of dead and wounded. War widows were banned from wearing black as it would be bad for morale. Reports of the “gallant and desperate attacks” against Turkey did not include the word failed.

Many estate agents added “No Soldiers’ Wives” to advertisements for houses for rent.

The director of education, Frank Tate, an ardent imperial loyalist, saw the war as “a great opportunity to train our girls and boys in habits of usefulness and devotion to a common cause”. Girls knitted socks, boys gathered wool from fences and scrub, sold bottles, scrap metal, and rabbits.

In 1915 the federal government wrote to every man in Australia aged between 18 and 60 to ask when they would enlist and, if not, why not.

Despite the carnival atmosphere, despite the picture shows and posters, despite the combined power of politicians, church leaders, military, business and financial interests, Australia voted against conscription in two referendums. (Wonthaggi voted no, although Victoria voted yes.)

Those who campaigned against conscription deserve to be honoured for their foresight and courage - they must have saved many thousands of Australian lives.

At Gallipoli in May 1915, a ceasefire to bury the dead allowed Turks and Anzacs to exchange cigarettes. The Australians found that Johnny Turk was not an evil fiend, just a soldier defending his homeland, and as miserable and exhausted as themselves.

In A Fortunate Life, Albert Facey described the nine-month Gallipoli campaign as “the worst months of my life and it was all for nothing. I would have stayed behind if I had known.”

After the war

At the end of the war, a letter to the editor of the Powlett Express expressed the hope that the returned Anzacs would be treated better than the returned Boer vets. The hope was futile.

Four out of five soldiers who survived the war were damaged or disabled in some way. One veteran died 10 days after arriving home in Inverloch. One third of returnees were unable to work due to disability. By 1926, 23,000 were in hospital. By 1929, it was 50,000.

Some could not help blaming themselves for tragic events that were out of their control. “I could not stop to help my mate who had been hit.” “Why did I live when Bill beside me got killed?” “If I had been a woman I would have cried.”

For some the welcome home was less than they expected. I have heard that some of those who returned to Wonthaggi walked around rather than through the victory arch built to welcome them home.

The women who had been left at home rate less mention than the men in combat but their suffering and sacrifice was surely as painful. Some soldiers who had stifled their emotions to cope with the killing and gore could not resurrect their humane caring qualities. Many children grew up with a father they hardly knew, a detached stranger who came to live with them.

Terri Allen wrote: “My mother’s class at Wonthaggi Primary School in the 1920s had a very tetchy teacher. To pay him back, students regularly dropped objects to create a loud noise. This sent him berserk. It wasn’t till decades later that the perpetrators learned he had returned shell shocked from the trenches in France.”

Sam Gatto remembers as a child playing in the Wonthaggi Citizens Band on Anzac Day when the World War 1 veterans were still spitting angry about the war. They may have been angry at the tactical bungling, disillusioned by the treatment they received when they came home or maybe even angry with themselves for believing the propaganda that convinced them to volunteer.

In 1920 only 12 of the 125 men of the district who were eligible turned up to receive their 1914-15 star medal. Wonthaggi’s war veterans didn’t want a war memorial. They formed the Returned Soldiers Sailors and Nurses Co-op. They used the memorial funds to buy a cinema that could be used by the whole community and raised funds for the families of their dead, blind, lame and mutilated mates.

A common quote from family members around Gippsland is “He never spoke about it”. Of the seven returned soldiers with family connections to my street, none left written memories.

Alexander Shackelford returned to Glen Forbes. His son said that whenever anything to do with war came on TV, he would leave the room and find something to do. Keith Tooley never spoke about the war except to say his brother had it worse than him.

In Citizen to Soldier, one soldier remarks: “When I look back I wonder how anyone of sane mind could entertain the idea that we were going 12 thousand miles to save Australia. I still cannot realise that I actually volunteered.”

Another said: “At the age of 75 years I ask myself was the army a coward’s way out.”

What we learnt

In 1916, a British royal commission found that even if the Gallipoli campaign had succeeded, it would have made no difference to the outcome of the war. This inconsequential campaign claimed the lives of some 56,000 Allied soldiers (principally British and French but including more than 8000 Australians, as well as New Zealanders and Indians) and about the same number of Turks, who, after all, were defending their country.

An Australian general, Cyril Brudenell White, admitted privately that he thought Churchill ought to be hanged as surely as any criminal for the disaster at Gallipoli.

Over the years, I have talked to many returned soldiers from many different countries. In many accents, it was always the same message: “War is a terrible thing, son.” “There is no glory in war.” “I don’t want to speak about the war. I have seen and done things I want to forget.”

Ted Matthews, who was at Gallipoli for the entire campaign, had one message: “For God’s sake do not glorify Gallipoli. It was a terrible mistake and young people should be told that.” We are living in the most peaceful era of human existence but the solemnity and contemplation that Anzac Day should inspire is being replaced with fireworks and fanfare.

There is little discussion about what we should have learned about the causes and consequences of war, or the alternatives. In 2003 only two senators spoke against Australia joining another foreign war, the invasion of Iraq.

Last November, Tony Abbott suggested a unilateral invasion of Iraq by 3500 Australian troops. He took the idea to Australia’s leading military planners who told him it would be disastrous.

History is filled with what look to us like unnecessary wars. In the future, today won’t look much different.

* Citizen to Soldier: Australia before the Great War: recollections of members of the first A.I.F. Edited by J.N.I. Dawes and L.L. Robson.

COMMENTS

June 7, 2015

I am a little late in commenting on this great article but I wanted to commend Frank's insight and was glad to read something which didn't glorify Anzac Day. This year we were bombarded with photos and regalia, due in part to the 100 year anniversary. Yet it was really a celebration and that in itself is a frightful thing.

What are we doing glorifying war? What are we doing making an act of aggression something noble? Of course the young men and women who died, did so for what they perceived as a noble cause, but is it? How can the slaughter of so many in any way be something that we want to honour?

The speeches, the marches, the ridiculous statements that these men and women are protecting our freedom, all glorify war and all cause other men and women to sign up and give their lives. But what are they giving their lives for? Not for freedom, not for defense, not for what is right, although that is what they believe. They give their freedom because somebody somewhere is greedy and wants more and unlike in the days of old, where the kings led the way in battle, now the rich stay home and send the poor out to fight.

Make a new rule that those who want to declare war, lead the charge and lets see how many want to follow that road then.

I do not mean any disrespect to those who have fought but I can no longer abide the lies that are told in glorifying their deaths and the pretense that what they did was a necessary action.

Thanks Frank, for not just towing the company line and for raising valid points that are often overlooked in the media warmongering.

Jacqui Paulson

April 30, 2015

Before Federation we sent forces to two overseas conflicts: HMCSS Victoria participated in the Maori Wars and a NSW contingent fought against the "Mad Mahdi" in the Sudan in 1885.

In 1900 Mr Henry Bourne Higgins rose from his seat in the Victorian Legislative Assembly. The Government was deciding to send a contingent of Victorians to support the British fight against rebellious Chinese. Higgins, doubting the wisdom of the decision stated that "The people will be wanting to know whether we in these colonies are to be expected to volunteer each time to contribute valuable lives and money in aid of wars which may not interest us directly".

Higgins went on to become Federal Attorney General and, more famously, as Arbitration Commissioner bought down the Sunshine Harvester decision that set the first minimum wage standard in Australia.

Our soldiers returned from The War in South Africa in 1902. Australia was a young nation. We have since lost many brave soldiers in foreign fields. Across the distance of time some campaigns, such as the fight against the "Bolsheviks" in 1919, might seem unjustified.

Soldiers go where we send them. When a Prime Minister talks about "sending the troops" he does so because we have elected him to that position. The overall lesson is that we need to be careful about who we choose to lead us.

Many service people return to us bearing the scars, physical and psychological, of their service to Australia. We don't always look after them well. How many World War 1 veterans lived for decades, crippled and bed ridden, hidden away in Anzac Hostels and private homes? The nature of war has changed greatly but the effect on those who serve is still devastating.

Roy Longmore was one of the last of the original Anzacs. His great-granddaughter, Carly Longmore said, at his funeral service in Melbourne, "It is unbelievable to think that Roy has lived with 87 years of graphic memories of those bloody battles of war. Eighty-seven years of waking up every morning and continuing life as normal, 87 years of being nothing less than a hero, 87 years of never once complaining of it."

Geoff Ellis, Wattle Bank

April 27, 2015

What a disingenuous, jaundiced and cowardly view of history. No doubt this man would bend his knee to tyranny provided he kept his life. You apparently have no concept of duty, responsibility and honour.

The article has simply cherry picked a few supposed truths relating to war to suit a personal point of view based on a distorted premise.

I suppose you see yourself as a pacifist. As a Vietnam Veteran I say you are not. But I do know that all of the Veterans I know and come in contact with as a Veterans pension and welfare officer are pacifists.

Australia has never actively pursued or declared war on other countries as you suggest in your article. You make much of propaganda in your article with no reference to German propaganda in World War One.

Your view insults this country which gives you the comfort and security to freely express you views.

Rod Gallagher (Vietnam Veteran), Inverloch

April 26, 2015

When I saw the introduction to this article yesterday, ANZAC Day, I was saddened then disappointed and then angry.

I think it is wrong that the article has started with a quote by “Tony Abbott” as it implies he is the protagonist in this story and shows a certain amount of bias, thereby damaging your story. It would have been more correct to quote the “Prime Minister of Australia”. I also remember our meeting at Tank Hill, Frank, when you recognised my surname and asked me for any stories I may have about the hardships my distant ancestor may have experienced after the war. I only remember his courage.

The government department responsible for our sailors, soldiers and air personnel is called the Department of Defence, not the department of offence. War is not pretty and it is too easy to dredge up examples of how brutal and, ultimately, futile it is. In these times of negative journalism, how about we try to find some positives in the world. Even war has positives like freeing people from oppression and cruelty, creating employment either as a soldier or working in factories making supplies and, yes, munitions or on the land. Many medical advances were also made. Nobody wants to go to war, including those trained for it. Until human nature is such that it has learned to live together, accepting everyone’s differences, there will continue to be differences. Until there is more equality in the world, there will continue to be disputes.

The shape of the world has changed significantly since 1914 and surely it is the responsibility of all nations to ensure that the people of the world can live in peace, without persecution. If you saw a bully beating up someone in the street, would you ignore the person’s distress and cross to the other side of the road or would you go to their assistance? If you were the one being beaten up, would you want someone to help you?

I was saddened that such an article was published on a day when we were commemorating and remembering those who were merely doing their job, in the service of their country. It reminded me of the reception our soldiers, returning from the Vietnam conflict, received by the government and citizens of the day, it was atrocious. As far as the atrocities during WWI are concerned, wouldn’t it be wonderful if we knew back then what we know today?

Pamela Jacka, Wonthaggi

F28367 L/cpl P. R. Jacka WRAAC Ret’d

Advance Australia Fair & God Defend New Zealand

April 26, 2015

A marvellous article by Frank Coldebella, giving a much more nuanced historical view of the Anzac story. It is a great reminder to see the pressure put on those poor young fellows to enlist in a war they in fact knew nothing about, and the bitterness and disillusion of so many who returned. Not to mentioned the damaged lives of those around them.

I expect that very few of those fostering this modern myth of the noble heroes fighting for our freedom would like to hear about the reality.

Jenny Skewes, Ventnor

April 26, 2015

Thank you Frank Coldebella. You stated what I have been thinking but with great research. Ted Matthews is right and we should listen to the message from those who were there. There is a reason governments jump eagerly into war. In the present case it is to hide a deeply unpopular government. Spend a few young lads lives and look like an action prime minister.

Michael Whelan, Cowes

April 26, 2015

Great story, Frank. We need to reappraise the idea that our country was born in an act of war.

Andrew Shaw, Brisbane

April 26, 2015

Thank you Frank for speaking out with courage and passion in a truly Australian way. It is great to be reminded at this time that the freedom to call it as we see it is a privilege to be treasured, and how essential it is in securing our future as an open and fair society.

Tim Shannon, Ventnor.

April 26, 2015

Thanks, Frank, for some great research and your insights on Australian warmongering. Reading the newspapers of 1914-15 now, one is struck by the clownish absurdity of the anti-German, anti-Turkish propaganda but in 1915 only those with an intellectual support base – principally unions and socialist organisations – could have seen through the barrage of jingoism in the newspapers, from the pulpits and from Australia’s political leaders. What courage it must have taken for an isolated young man to resist the taunts, the threats and most of all the emotional blackmail about “mates calling from Gallipoli”.

I was about to say we’re more sceptical today but perhaps I’m kidding myself. In 2065, Australians will be as astonished by the jingoism that led to the 2003 invasion of Iraq. We are still trying to pick sides in wars that we don’t understand and sending young people to pay the price for our ignorance.

Catherine Watson, Wonthaggi

ON WINNING the Americas Cup in 1983, Alan Bond described it as the greatest victory since Gallipoli. How did a disastrous failed invasion of a Muslim country that posed no threat to Australia come to be the symbol not just of victory but of our nationhood?

The first casualty in war is the truth and the untruth often lies in the things that are not reported. Some things don’t seem important at the time; others are deleted to make our history look better.

“Australia is not a country that goes looking for trouble,” our Prime Minister, Tony Abbott, recently stated. Our history tells a different story.

In 1899 cheering crowds, patriotic music and the prayers of clergymen saw off 1200 men to the Boer War.

In 1900, more went to fight the Chinese in China. Henry Lawson wrote to the Bulletin: “Some of us are willing – wilfully, blindly eager mad – to cross the sea and shoot men whom we never saw and whose quarrel we do not and cannot understand”.

In 1908 the Australian government introduced compulsory night and weekend military training for males aged 12-26. When war was declared in 1914, Australia had a well-trained, disciplined army itching for a fight.

On seeing a group of soldiers leaving Melbourne to fight, a Mrs Massey wrote: “I think I never saw a more joyous party. They reminded me of happy school boys bound for some party of pleasure ...”

According to the Argus newspaper, “Victoria was thrilled to the core” when war was declared. There was “overwhelming excitement and jubilation”. The same day a patriotic mob in Melbourne attacked the German club and Chinese quarters in little Bourke Street, smashing windows, looting property and terrorising the inhabitants.

In poor country towns, the news of war inspired parades, pledges of loyalty, concerts, patriotic funds and the ringing of church bells. Farmers donated horses and bullocks. The atmosphere, according to John McQuilton, was “almost festive”.

“The freest and best country on god’s earth calls to her sons for aid,” Prime Minister Billy Hughes stated. “Destiny has given you a great opportunity.”

Cartoon by Natasha Williams-Novak

Powlett Express

In 1908 the Australian government introduced compulsory night and weekend military training for males aged 12-26. When war was declared in 1914, Australia had a well-trained, disciplined army itching for a fight.

On seeing a group of soldiers leaving Melbourne to fight, a Mrs Massey wrote: “I think I never saw a more joyous party. They reminded me of happy school boys bound for some party of pleasure ...”

According to the Argus newspaper, “Victoria was thrilled to the core” when war was declared. There was “overwhelming excitement and jubilation”. The same day a patriotic mob in Melbourne attacked the German club and Chinese quarters in little Bourke Street, smashing windows, looting property and terrorising the inhabitants.

In poor country towns, the news of war inspired parades, pledges of loyalty, concerts, patriotic funds and the ringing of church bells. Farmers donated horses and bullocks. The atmosphere, according to John McQuilton, was “almost festive”.

“The freest and best country on god’s earth calls to her sons for aid,” Prime Minister Billy Hughes stated. “Destiny has given you a great opportunity.”

The Railways refused to employ single men because “single men should be at the front”.

In September, 1914, the Australian Government introduced censorship of press and mail. The War Precautions Act had wide powers against all opponents of war. The sale of anti-war papers was prohibited.

In the newspapers, the war was referred to as “the big game” and “the greatest sport of all”. It promised volunteers travel, action and adventure, then home by Christmas. A common fear among volunteers was that the fighting would be over before they got there.

In 1915 C.J. Dennis wrote: “What’s just plain stoush with us right here today is valour if you’re far enough away”.

“THE SPIRITS OF YOUR DEAD PALS CALL OUT,” shouted an enlistment poster. “WE HAVE GIVEN ALL. ARE YOU GOING TO BETRAY US?”

The Miners Union told its members to ignore the recruitment ads. “War increases the misery of the poor,” the union stated. The “blood-spilling business” only enriches a few.

Protestant churches passed resolutions in favour of war. An Anglican preacher told his congregation: “Christ submitted himself to the conscription of heaven. He came to obey and carry out the act of death imposed upon him … Christians must therefore vote for conscription.”

In a collection of interviews with First World War veterans published in 1972*, a South Gippsland returned soldier said he sought the advice of his local minister before enlisting. “He convinced me that the war would end all wars and that it was right to go …”

It was a difficult time for those who wanted to obey Jesus’s command to “Love your enemies”. In some country towns, pleas for peace and sanity became acts of treason opponents to conscription were tarred and feathered. In Melbourne soldiers disrupted a peace meeting during a speech by Vida Goldstein. The Prime Minister called anti-conscriptionists “vipers, cowards, dirty dogs and parasites”.

Casualty lists disguised the real number of dead and wounded. War widows were banned from wearing black as it would be bad for morale. Reports of the “gallant and desperate attacks” against Turkey did not include the word failed.

Many estate agents added “No Soldiers’ Wives” to advertisements for houses for rent.

The director of education, Frank Tate, an ardent imperial loyalist, saw the war as “a great opportunity to train our girls and boys in habits of usefulness and devotion to a common cause”. Girls knitted socks, boys gathered wool from fences and scrub, sold bottles, scrap metal, and rabbits.

In 1915 the federal government wrote to every man in Australia aged between 18 and 60 to ask when they would enlist and, if not, why not.

Despite the carnival atmosphere, despite the picture shows and posters, despite the combined power of politicians, church leaders, military, business and financial interests, Australia voted against conscription in two referendums. (Wonthaggi voted no, although Victoria voted yes.)

Those who campaigned against conscription deserve to be honoured for their foresight and courage - they must have saved many thousands of Australian lives.

At Gallipoli in May 1915, a ceasefire to bury the dead allowed Turks and Anzacs to exchange cigarettes. The Australians found that Johnny Turk was not an evil fiend, just a soldier defending his homeland, and as miserable and exhausted as themselves.

In A Fortunate Life, Albert Facey described the nine-month Gallipoli campaign as “the worst months of my life and it was all for nothing. I would have stayed behind if I had known.”

After the war

At the end of the war, a letter to the editor of the Powlett Express expressed the hope that the returned Anzacs would be treated better than the returned Boer vets. The hope was futile.

Four out of five soldiers who survived the war were damaged or disabled in some way. One veteran died 10 days after arriving home in Inverloch. One third of returnees were unable to work due to disability. By 1926, 23,000 were in hospital. By 1929, it was 50,000.

Some could not help blaming themselves for tragic events that were out of their control. “I could not stop to help my mate who had been hit.” “Why did I live when Bill beside me got killed?” “If I had been a woman I would have cried.”

For some the welcome home was less than they expected. I have heard that some of those who returned to Wonthaggi walked around rather than through the victory arch built to welcome them home.

The women who had been left at home rate less mention than the men in combat but their suffering and sacrifice was surely as painful. Some soldiers who had stifled their emotions to cope with the killing and gore could not resurrect their humane caring qualities. Many children grew up with a father they hardly knew, a detached stranger who came to live with them.

Terri Allen wrote: “My mother’s class at Wonthaggi Primary School in the 1920s had a very tetchy teacher. To pay him back, students regularly dropped objects to create a loud noise. This sent him berserk. It wasn’t till decades later that the perpetrators learned he had returned shell shocked from the trenches in France.”

Sam Gatto remembers as a child playing in the Wonthaggi Citizens Band on Anzac Day when the World War 1 veterans were still spitting angry about the war. They may have been angry at the tactical bungling, disillusioned by the treatment they received when they came home or maybe even angry with themselves for believing the propaganda that convinced them to volunteer.

In 1920 only 12 of the 125 men of the district who were eligible turned up to receive their 1914-15 star medal. Wonthaggi’s war veterans didn’t want a war memorial. They formed the Returned Soldiers Sailors and Nurses Co-op. They used the memorial funds to buy a cinema that could be used by the whole community and raised funds for the families of their dead, blind, lame and mutilated mates.

A common quote from family members around Gippsland is “He never spoke about it”. Of the seven returned soldiers with family connections to my street, none left written memories.

Alexander Shackelford returned to Glen Forbes. His son said that whenever anything to do with war came on TV, he would leave the room and find something to do. Keith Tooley never spoke about the war except to say his brother had it worse than him.

In Citizen to Soldier, one soldier remarks: “When I look back I wonder how anyone of sane mind could entertain the idea that we were going 12 thousand miles to save Australia. I still cannot realise that I actually volunteered.”

Another said: “At the age of 75 years I ask myself was the army a coward’s way out.”

What we learnt

In 1916, a British royal commission found that even if the Gallipoli campaign had succeeded, it would have made no difference to the outcome of the war. This inconsequential campaign claimed the lives of some 56,000 Allied soldiers (principally British and French but including more than 8000 Australians, as well as New Zealanders and Indians) and about the same number of Turks, who, after all, were defending their country.

An Australian general, Cyril Brudenell White, admitted privately that he thought Churchill ought to be hanged as surely as any criminal for the disaster at Gallipoli.

Over the years, I have talked to many returned soldiers from many different countries. In many accents, it was always the same message: “War is a terrible thing, son.” “There is no glory in war.” “I don’t want to speak about the war. I have seen and done things I want to forget.”

Ted Matthews, who was at Gallipoli for the entire campaign, had one message: “For God’s sake do not glorify Gallipoli. It was a terrible mistake and young people should be told that.” We are living in the most peaceful era of human existence but the solemnity and contemplation that Anzac Day should inspire is being replaced with fireworks and fanfare.

There is little discussion about what we should have learned about the causes and consequences of war, or the alternatives. In 2003 only two senators spoke against Australia joining another foreign war, the invasion of Iraq.

Last November, Tony Abbott suggested a unilateral invasion of Iraq by 3500 Australian troops. He took the idea to Australia’s leading military planners who told him it would be disastrous.

History is filled with what look to us like unnecessary wars. In the future, today won’t look much different.

* Citizen to Soldier: Australia before the Great War: recollections of members of the first A.I.F. Edited by J.N.I. Dawes and L.L. Robson.

COMMENTS

June 7, 2015

I am a little late in commenting on this great article but I wanted to commend Frank's insight and was glad to read something which didn't glorify Anzac Day. This year we were bombarded with photos and regalia, due in part to the 100 year anniversary. Yet it was really a celebration and that in itself is a frightful thing.

What are we doing glorifying war? What are we doing making an act of aggression something noble? Of course the young men and women who died, did so for what they perceived as a noble cause, but is it? How can the slaughter of so many in any way be something that we want to honour?

The speeches, the marches, the ridiculous statements that these men and women are protecting our freedom, all glorify war and all cause other men and women to sign up and give their lives. But what are they giving their lives for? Not for freedom, not for defense, not for what is right, although that is what they believe. They give their freedom because somebody somewhere is greedy and wants more and unlike in the days of old, where the kings led the way in battle, now the rich stay home and send the poor out to fight.

Make a new rule that those who want to declare war, lead the charge and lets see how many want to follow that road then.

I do not mean any disrespect to those who have fought but I can no longer abide the lies that are told in glorifying their deaths and the pretense that what they did was a necessary action.

Thanks Frank, for not just towing the company line and for raising valid points that are often overlooked in the media warmongering.

Jacqui Paulson

April 30, 2015

Before Federation we sent forces to two overseas conflicts: HMCSS Victoria participated in the Maori Wars and a NSW contingent fought against the "Mad Mahdi" in the Sudan in 1885.

In 1900 Mr Henry Bourne Higgins rose from his seat in the Victorian Legislative Assembly. The Government was deciding to send a contingent of Victorians to support the British fight against rebellious Chinese. Higgins, doubting the wisdom of the decision stated that "The people will be wanting to know whether we in these colonies are to be expected to volunteer each time to contribute valuable lives and money in aid of wars which may not interest us directly".

Higgins went on to become Federal Attorney General and, more famously, as Arbitration Commissioner bought down the Sunshine Harvester decision that set the first minimum wage standard in Australia.

Our soldiers returned from The War in South Africa in 1902. Australia was a young nation. We have since lost many brave soldiers in foreign fields. Across the distance of time some campaigns, such as the fight against the "Bolsheviks" in 1919, might seem unjustified.

Soldiers go where we send them. When a Prime Minister talks about "sending the troops" he does so because we have elected him to that position. The overall lesson is that we need to be careful about who we choose to lead us.

Many service people return to us bearing the scars, physical and psychological, of their service to Australia. We don't always look after them well. How many World War 1 veterans lived for decades, crippled and bed ridden, hidden away in Anzac Hostels and private homes? The nature of war has changed greatly but the effect on those who serve is still devastating.

Roy Longmore was one of the last of the original Anzacs. His great-granddaughter, Carly Longmore said, at his funeral service in Melbourne, "It is unbelievable to think that Roy has lived with 87 years of graphic memories of those bloody battles of war. Eighty-seven years of waking up every morning and continuing life as normal, 87 years of being nothing less than a hero, 87 years of never once complaining of it."

Geoff Ellis, Wattle Bank

April 27, 2015

What a disingenuous, jaundiced and cowardly view of history. No doubt this man would bend his knee to tyranny provided he kept his life. You apparently have no concept of duty, responsibility and honour.

The article has simply cherry picked a few supposed truths relating to war to suit a personal point of view based on a distorted premise.

I suppose you see yourself as a pacifist. As a Vietnam Veteran I say you are not. But I do know that all of the Veterans I know and come in contact with as a Veterans pension and welfare officer are pacifists.

Australia has never actively pursued or declared war on other countries as you suggest in your article. You make much of propaganda in your article with no reference to German propaganda in World War One.

Your view insults this country which gives you the comfort and security to freely express you views.

Rod Gallagher (Vietnam Veteran), Inverloch

April 26, 2015

When I saw the introduction to this article yesterday, ANZAC Day, I was saddened then disappointed and then angry.

I think it is wrong that the article has started with a quote by “Tony Abbott” as it implies he is the protagonist in this story and shows a certain amount of bias, thereby damaging your story. It would have been more correct to quote the “Prime Minister of Australia”. I also remember our meeting at Tank Hill, Frank, when you recognised my surname and asked me for any stories I may have about the hardships my distant ancestor may have experienced after the war. I only remember his courage.

The government department responsible for our sailors, soldiers and air personnel is called the Department of Defence, not the department of offence. War is not pretty and it is too easy to dredge up examples of how brutal and, ultimately, futile it is. In these times of negative journalism, how about we try to find some positives in the world. Even war has positives like freeing people from oppression and cruelty, creating employment either as a soldier or working in factories making supplies and, yes, munitions or on the land. Many medical advances were also made. Nobody wants to go to war, including those trained for it. Until human nature is such that it has learned to live together, accepting everyone’s differences, there will continue to be differences. Until there is more equality in the world, there will continue to be disputes.

The shape of the world has changed significantly since 1914 and surely it is the responsibility of all nations to ensure that the people of the world can live in peace, without persecution. If you saw a bully beating up someone in the street, would you ignore the person’s distress and cross to the other side of the road or would you go to their assistance? If you were the one being beaten up, would you want someone to help you?

I was saddened that such an article was published on a day when we were commemorating and remembering those who were merely doing their job, in the service of their country. It reminded me of the reception our soldiers, returning from the Vietnam conflict, received by the government and citizens of the day, it was atrocious. As far as the atrocities during WWI are concerned, wouldn’t it be wonderful if we knew back then what we know today?

Pamela Jacka, Wonthaggi

F28367 L/cpl P. R. Jacka WRAAC Ret’d

Advance Australia Fair & God Defend New Zealand

April 26, 2015

A marvellous article by Frank Coldebella, giving a much more nuanced historical view of the Anzac story. It is a great reminder to see the pressure put on those poor young fellows to enlist in a war they in fact knew nothing about, and the bitterness and disillusion of so many who returned. Not to mentioned the damaged lives of those around them.

I expect that very few of those fostering this modern myth of the noble heroes fighting for our freedom would like to hear about the reality.

Jenny Skewes, Ventnor

April 26, 2015

Thank you Frank Coldebella. You stated what I have been thinking but with great research. Ted Matthews is right and we should listen to the message from those who were there. There is a reason governments jump eagerly into war. In the present case it is to hide a deeply unpopular government. Spend a few young lads lives and look like an action prime minister.

Michael Whelan, Cowes

April 26, 2015

Great story, Frank. We need to reappraise the idea that our country was born in an act of war.

Andrew Shaw, Brisbane

April 26, 2015

Thank you Frank for speaking out with courage and passion in a truly Australian way. It is great to be reminded at this time that the freedom to call it as we see it is a privilege to be treasured, and how essential it is in securing our future as an open and fair society.

Tim Shannon, Ventnor.

April 26, 2015

Thanks, Frank, for some great research and your insights on Australian warmongering. Reading the newspapers of 1914-15 now, one is struck by the clownish absurdity of the anti-German, anti-Turkish propaganda but in 1915 only those with an intellectual support base – principally unions and socialist organisations – could have seen through the barrage of jingoism in the newspapers, from the pulpits and from Australia’s political leaders. What courage it must have taken for an isolated young man to resist the taunts, the threats and most of all the emotional blackmail about “mates calling from Gallipoli”.

I was about to say we’re more sceptical today but perhaps I’m kidding myself. In 2065, Australians will be as astonished by the jingoism that led to the 2003 invasion of Iraq. We are still trying to pick sides in wars that we don’t understand and sending young people to pay the price for our ignorance.

Catherine Watson, Wonthaggi