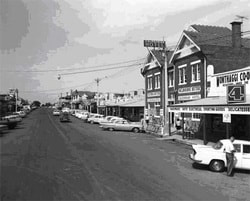

Graham Street, Wonthaggi, 1963

Graham Street, Wonthaggi, 1963 All over the world, 1968 was a revolutionary year. Frank Coldebella was in year 9 and watched the spark of revolution reach Wonthaggi.

By Frank Coldebella

IN 1968, fires in the Dandenongs destroyed 34 homes. The Beatles released Revolution. The Vietnam War was at its height and the Tet offensive convinced Australian voters that the war was an unwinnable disaster. We had been lied to again. In the village of My Lai, 563 civilians were killed. Richard Nixon declared war on drugs. In Melbourne, mounted police charged 2000 anti-war demonstrators in the city’s biggest day of riots. Gough Whitlam was elected leader of the ALP.

At the Mexico Olympics, Aussie sprinter Peter Norman wore an anti-racism badge on the dais when John Carlos and Tommie Smith made their famous gesture at the 1968 Olympics medal ceremony and was crucified by the media and sporting authorities. In the US, Robert Kennedy was assassinated, followed by the man with the dream, Martin Luther King. King’s death sparked rioting and fires in 100 US cities. Thirty-nine people were killed, 20,000 were arrested and 11,000 troops surrounded the White House. Students protested and were killed all over the world, including Kent State University. I still feel the tears when I hear the lyrics “What if you knew her and found her dead on the ground”. The Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia, Apollo 8 went round the moon and sent back pictures of our tiny blue and white planet alone in the middle of nowhere.

There were no current affairs shows on TV so lots of people got The Herald to read what was happening. I was in year 9 and was also doing a paper round after school. All this strife and turmoil, excitement and disbelief combined with the “horror movie “images on the 6.30pm news made it a boom year for selling papers.

The world might have been changing but the shops in Graham Street and McBride Avenue still had veranda posts and open, uneven, bluestone gutters. In Reed Crescent, we still had our bread and milk delivered by horse and cart. The postman came on a bicycle twice a day and blew a whistle when he put the mail in the box. One shop in Graham Street still had the original dirt floor. There were three pubs, all with large log fires. There were no water meters, no roundabouts, no seatbelts and no real estate agents. Telegrams were delivered by bicycles with no gears. Phone numbers had two or three digits. There were two barber shops, seven butcher shops, two banks, no supermarkets and about eight milk bars. The average dairy farm had 56 cows.

Some homes didn’t have a fence separating them. Many had a small gate connecting them. It seems to me there were about five kids for every two adults. In the town, jogging was a form of transport for kids. Advertisers had not yet perfected the art of making people feel deprived and inadequate. The number of people marrying out of their religion was increasing.

The mayor was Bill Robertson, a 31-year-old schoolteacher from Ballarat, TV was black and white, as was the content of most of the news. You were either with us – that is, the US – or with the Commos. You were either a Catholic, a Proddie or a heathen.

The old St Joe’s Catholic Church in McKenzie Street was still fenced with high steel mesh topped with barbed wire, visible evidence of more fearful and divisive times.

On Thursday and Friday nights, the mine bus stopped out the front of the cream and green Powlett Hotel. Behind its frosted windows you could play quoits, darts, hookey or pool. There was worn red and cream checked lino on the floor. Heysen’s painting Droving into the Light hung over the large open fireplace. Like most pubs, it had a piano in the ladies’ lounge and on Thursday and Friday nights a group of seniors would gather around it singing with all their hearts the good old songs that made them feel like teenagers again.

On Saturday night Graham Street was full of teenagers from all over the district A rumour went around that a Rotary exchange student from Leongatha had been sent home early from Chicago for speaking out against the war in Vietnam. We never did get to hear her side of the story.

We saw To Sir with Love at the Union Theatre, where Tilio Moresco was the bouncer, and boy could he bounce! He had to. If the movie was dull, some of the audience provided some commentary that descended into mayhem and hysterics.

Norma and Kevin Moresco and their six kids were in the Astor cafe and it was the place to be on a Friday after school. In one corner they had a jukebox. It must have weighed about half a ton and had about 40 songs on it – Beatles, Rolling Stones, Simon and Garfunkle, the Beach Boys, the Monkeys, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Aretha Franklin, Diana Ross, Neil Diamond, the Bee Gees, the Doors and Bob Dylan.

The times were definitely a-changing – it was a great time to be a teenager. There was a gap between our parents’ generation and ours. They had grown up with deprivation and war. By the mid ‘60s we were absorbed in cartoons and pop. Because of the war or over-work, lots of kids hardly knew their father. For some Anglos, the fear of Asians and wogs would take years to unlearn. At 14, we didn’t know where we were going, we just wanted to be doing what everybody else was doing. Fortunately for some of us there were still shacks at the beach when you really needed to escape the oppression of society and the world of adults. Here nothing was black and white. Here the beauty, freedom, adventure, challenge gave a glorious release from the cruelty and humiliation of school. The sounds, the smell of salty air mixed with tea tree and banksia and lots of idle time and space for exploring, dreaming and imagining.

Opposite the Powlett Hotel at 102 Graham Street there is still a small shop. Today it sells cartridges. Back then it had a much smaller window and the sign above it read Tony Gazzola Boot Repairs. It was a tiny shop, dark, chock-a-block full of shoes and boots, rolls of leather and bundles of leather laces. It was so dark inside that you had to stop just inside the door and wait for your eyes to adjust to the lack of light. There was only room inside for two people and a chair.

Tony, a small, round, humble, smiling, old cobbler with a leather apron peered over his specs. He could be hammering hobnails into a miner’s boot or putting new soles on a favourite pair of worn shoes. With the dim light shining on his specs and bald head, he looked like a Rembrandt painting or a character from a kids’ storybook.

Nesci’s wine salon stood where the Telecom site is in Mackenzie Street. Here after school on Friday you’d find Jim Glover, Mr Osborne and a few other school teachers, together with a couple of Italians, including Tony Capuso, deep in discussion about everything and anything. Mr I R Osborne copped some flak around town for being a conscientious objector. I think he only taught for one year. It was Jim Glover, my art teacher that year, who first warned me about commercial newspapers and what they did with stories. He was also among the first to speak up in defence of our native vegetation and wildlife, which led to a flora and fauna reserve being established at Harmers Haven. The Phillip Island conservation society was formed in May that year.

The teachers who arrived at the tech/high in the late ‘60s had a Renaissance-like effect on the whole district. They did not use physical violence or verbal abuse as teaching aids. A few of them even liked Italian food.

New teachers and others coming to Wonthaggi have always been like the king tide that replenishes a stagnating rock pool at the beach, disturbing the torpor, bringing fresh nutrients of ideas and imagination. These new arrivals helped us get our library and swimming pool. How do you thank those who help to light the way out of the dark? We owe the teachers a lot.

For me, the best thing that happened that year was the moves to get our library. There was a small library at the Workmen’s Club, referred to by some as “the red shed”. On Friday nights, a wise and learned old Scot called Joe Foster was in charge. He had a hut at Cutlers Beach, which was an open house. Joe told me that John Steinbeck had died and suggested I read his book The Grapes of Wrath. It wasn’t until about 15 years later that I did.

Old Joe would have agreed with his fellow Scot, author Andrew O’Hagan, who wrote: “Great literature helps you to live your life. Great literature never goes away. It tells us what our culture has done, and what it has failed to do. Literature is not lifestyle, it is life. Literature is there, as they say, at the going down of the sun and in the morning. Like history, it is the news that stays news.”

But most blokes in those days preferred to drink beer – lots of beer. It was medication after a hard day’s work. On Thursday, Friday and Saturday, all three pubs and the Workmen’s Club were full. In the warmer months, with beers passing overhead, it was a job to squeeze myself and a bundle of papers through the forest of noisy boisterous smoking men.

The idealists and visionaries drank at the red shed. There were lots of different varieties of accents – Calabrian, Cornish, Dutch, Geordie, Scots, Yugoslav, Strayan, Tuscans, Veneto, Welsh, Yorkshire, all loudly sounding their different pronunciations. A few had been on opposite sides during the war. Here with the thick halo of smoke above them, the debates and discussions went on, as they must have on the bus and at work. The combination of those accents sounded like singing. Like some European choir of hard life, their song could have been “Come all ye faithful, whatever your faiths, for we are the world, we are the ones to make a brighter day.”

We weren’t allowed to finish with the papers until 7 o’clock so in winter, with all the sales and deliveries done, I’d head for the Workmen’s or Tabeners to read the paper and have a sarsaparilla in front of the fire. There was no shortage of advisers giving their version of life, politics, moneylenders, religion or war. The old pugs would say, “Always lead with your left, son.” Mentoring of children in mining towns probably goes back to the days when eight-year-olds worked down below. Some of their yarns would start with “When we was kids . . . “ I think that blokes then may have been more reliant on their mates than we are today. Three of my favourites were Eddie Pellizer, Len Wyhoon and a crusty old Scott called Sandy Dunbar. Ed Pellizer said, “You can learn something from even the biggest idiots.” They and many others spread the faith in humanity by leading exemplary lives.

It took me another two years to realise that most of the good men and women were either heathens or socialists and some were both. They believed it was the work you did, not the position you held that counted. Their message to us can be refined down to eight simple words: “We are all here to help one another.”

Pub blokes in those days were frank, fearless and no frills, confident about who we were and where we’d been. Some worked at the abattoirs, Cyclone and the cotton mills. There was the comic, the tragic and the legendary. Some were tough, gruff and surly, no doubt hurt by deprivation, war and hard physical work. There were some who had been taught from an early age that fighting with your fists was a necessary life skill; others were cheerful, kind and generous. The rest moved somewhere in between, depending on how things were going. I was called Mate, Sport, China, Magoo, Squire, Lad, Cobber, Paesan, Jock, Nugget, Sunshine, Bello, and Bastia, while some preferred not to speak at all. Forty years later, I asked Jim Donohue about one of these sad and humble “mutes”. Jim paused before answering. “The roof came down on his mate out at 20.” There’s an explanation for everything.

Nobody except Tom Gannon, the editor of The Powlett Express, dared questioned the Catholic priest who had warned us from the pulpit: “You’re not to have anything to do with that Joe Chambers.” Joe had spoken out against the war in Vietnam. By spring I was starting to doubt the Catholic three A’s: “Pray, Pay and Obey.” Tom would end up losing his newspaper.

Friday morning, 20th December, the day the Kirrak mine closed, was overcast. My mate Robert Legge and I rode our bikes out there. I thought about asking John Bordignon if he’d like to come but thought, “Naagh, he won’t be interested.”

At the mine I can remember an air of solemness, and apprehension about the future. Men were going to be out of work for the first time. I went into the engine room to watch the cable wound in. The inside of the engine room still had blackened timbers from the fire of 1964. There where several Italians on that last shift, but none of them seemed too concerned. A few joked around. I know for certain that some had seen and survived a lot worse in Europe.

When the last cage came up and the miners had walked away from it, someone yelled out “Have you locked it up, Harry?” We turned to look but Harry didn’t reply. Maybe he was lost for words.

I can remember some bloke scooped some helmets and all the time tokens off the board into a cardboard box. Someone gave a speech, thanking the workers. Some bloke gave me an old drill bit as a souvenir. The men from The Sun newspaper took some photos. When it was over, cars started to leave. A few men hung around in silence as if they’d just buried a good old mate and didn’t know what to say. Sometimes silence says a lot.

That was it. As we rode home for lunch, the sun came out. It would soon be summer and the sea would be starting to draw us out.

At about 5 o’clock, I was at the Workmen’s Club doing my last day of selling papers when the news went around town that Doc Sleeman had died.

The union blokes came up to the Workmen’s Club and got a couple of barrels of beer and set them up in the meeting room behind the Union Theatre, the room where so much had happened. Some of those miners stayed until it was very late. I reckon I would have too.

IN 1968, fires in the Dandenongs destroyed 34 homes. The Beatles released Revolution. The Vietnam War was at its height and the Tet offensive convinced Australian voters that the war was an unwinnable disaster. We had been lied to again. In the village of My Lai, 563 civilians were killed. Richard Nixon declared war on drugs. In Melbourne, mounted police charged 2000 anti-war demonstrators in the city’s biggest day of riots. Gough Whitlam was elected leader of the ALP.

At the Mexico Olympics, Aussie sprinter Peter Norman wore an anti-racism badge on the dais when John Carlos and Tommie Smith made their famous gesture at the 1968 Olympics medal ceremony and was crucified by the media and sporting authorities. In the US, Robert Kennedy was assassinated, followed by the man with the dream, Martin Luther King. King’s death sparked rioting and fires in 100 US cities. Thirty-nine people were killed, 20,000 were arrested and 11,000 troops surrounded the White House. Students protested and were killed all over the world, including Kent State University. I still feel the tears when I hear the lyrics “What if you knew her and found her dead on the ground”. The Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia, Apollo 8 went round the moon and sent back pictures of our tiny blue and white planet alone in the middle of nowhere.

There were no current affairs shows on TV so lots of people got The Herald to read what was happening. I was in year 9 and was also doing a paper round after school. All this strife and turmoil, excitement and disbelief combined with the “horror movie “images on the 6.30pm news made it a boom year for selling papers.

The world might have been changing but the shops in Graham Street and McBride Avenue still had veranda posts and open, uneven, bluestone gutters. In Reed Crescent, we still had our bread and milk delivered by horse and cart. The postman came on a bicycle twice a day and blew a whistle when he put the mail in the box. One shop in Graham Street still had the original dirt floor. There were three pubs, all with large log fires. There were no water meters, no roundabouts, no seatbelts and no real estate agents. Telegrams were delivered by bicycles with no gears. Phone numbers had two or three digits. There were two barber shops, seven butcher shops, two banks, no supermarkets and about eight milk bars. The average dairy farm had 56 cows.

Some homes didn’t have a fence separating them. Many had a small gate connecting them. It seems to me there were about five kids for every two adults. In the town, jogging was a form of transport for kids. Advertisers had not yet perfected the art of making people feel deprived and inadequate. The number of people marrying out of their religion was increasing.

The mayor was Bill Robertson, a 31-year-old schoolteacher from Ballarat, TV was black and white, as was the content of most of the news. You were either with us – that is, the US – or with the Commos. You were either a Catholic, a Proddie or a heathen.

The old St Joe’s Catholic Church in McKenzie Street was still fenced with high steel mesh topped with barbed wire, visible evidence of more fearful and divisive times.

On Thursday and Friday nights, the mine bus stopped out the front of the cream and green Powlett Hotel. Behind its frosted windows you could play quoits, darts, hookey or pool. There was worn red and cream checked lino on the floor. Heysen’s painting Droving into the Light hung over the large open fireplace. Like most pubs, it had a piano in the ladies’ lounge and on Thursday and Friday nights a group of seniors would gather around it singing with all their hearts the good old songs that made them feel like teenagers again.

On Saturday night Graham Street was full of teenagers from all over the district A rumour went around that a Rotary exchange student from Leongatha had been sent home early from Chicago for speaking out against the war in Vietnam. We never did get to hear her side of the story.

We saw To Sir with Love at the Union Theatre, where Tilio Moresco was the bouncer, and boy could he bounce! He had to. If the movie was dull, some of the audience provided some commentary that descended into mayhem and hysterics.

Norma and Kevin Moresco and their six kids were in the Astor cafe and it was the place to be on a Friday after school. In one corner they had a jukebox. It must have weighed about half a ton and had about 40 songs on it – Beatles, Rolling Stones, Simon and Garfunkle, the Beach Boys, the Monkeys, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Aretha Franklin, Diana Ross, Neil Diamond, the Bee Gees, the Doors and Bob Dylan.

The times were definitely a-changing – it was a great time to be a teenager. There was a gap between our parents’ generation and ours. They had grown up with deprivation and war. By the mid ‘60s we were absorbed in cartoons and pop. Because of the war or over-work, lots of kids hardly knew their father. For some Anglos, the fear of Asians and wogs would take years to unlearn. At 14, we didn’t know where we were going, we just wanted to be doing what everybody else was doing. Fortunately for some of us there were still shacks at the beach when you really needed to escape the oppression of society and the world of adults. Here nothing was black and white. Here the beauty, freedom, adventure, challenge gave a glorious release from the cruelty and humiliation of school. The sounds, the smell of salty air mixed with tea tree and banksia and lots of idle time and space for exploring, dreaming and imagining.

Opposite the Powlett Hotel at 102 Graham Street there is still a small shop. Today it sells cartridges. Back then it had a much smaller window and the sign above it read Tony Gazzola Boot Repairs. It was a tiny shop, dark, chock-a-block full of shoes and boots, rolls of leather and bundles of leather laces. It was so dark inside that you had to stop just inside the door and wait for your eyes to adjust to the lack of light. There was only room inside for two people and a chair.

Tony, a small, round, humble, smiling, old cobbler with a leather apron peered over his specs. He could be hammering hobnails into a miner’s boot or putting new soles on a favourite pair of worn shoes. With the dim light shining on his specs and bald head, he looked like a Rembrandt painting or a character from a kids’ storybook.

Nesci’s wine salon stood where the Telecom site is in Mackenzie Street. Here after school on Friday you’d find Jim Glover, Mr Osborne and a few other school teachers, together with a couple of Italians, including Tony Capuso, deep in discussion about everything and anything. Mr I R Osborne copped some flak around town for being a conscientious objector. I think he only taught for one year. It was Jim Glover, my art teacher that year, who first warned me about commercial newspapers and what they did with stories. He was also among the first to speak up in defence of our native vegetation and wildlife, which led to a flora and fauna reserve being established at Harmers Haven. The Phillip Island conservation society was formed in May that year.

The teachers who arrived at the tech/high in the late ‘60s had a Renaissance-like effect on the whole district. They did not use physical violence or verbal abuse as teaching aids. A few of them even liked Italian food.

New teachers and others coming to Wonthaggi have always been like the king tide that replenishes a stagnating rock pool at the beach, disturbing the torpor, bringing fresh nutrients of ideas and imagination. These new arrivals helped us get our library and swimming pool. How do you thank those who help to light the way out of the dark? We owe the teachers a lot.

For me, the best thing that happened that year was the moves to get our library. There was a small library at the Workmen’s Club, referred to by some as “the red shed”. On Friday nights, a wise and learned old Scot called Joe Foster was in charge. He had a hut at Cutlers Beach, which was an open house. Joe told me that John Steinbeck had died and suggested I read his book The Grapes of Wrath. It wasn’t until about 15 years later that I did.

Old Joe would have agreed with his fellow Scot, author Andrew O’Hagan, who wrote: “Great literature helps you to live your life. Great literature never goes away. It tells us what our culture has done, and what it has failed to do. Literature is not lifestyle, it is life. Literature is there, as they say, at the going down of the sun and in the morning. Like history, it is the news that stays news.”

But most blokes in those days preferred to drink beer – lots of beer. It was medication after a hard day’s work. On Thursday, Friday and Saturday, all three pubs and the Workmen’s Club were full. In the warmer months, with beers passing overhead, it was a job to squeeze myself and a bundle of papers through the forest of noisy boisterous smoking men.

The idealists and visionaries drank at the red shed. There were lots of different varieties of accents – Calabrian, Cornish, Dutch, Geordie, Scots, Yugoslav, Strayan, Tuscans, Veneto, Welsh, Yorkshire, all loudly sounding their different pronunciations. A few had been on opposite sides during the war. Here with the thick halo of smoke above them, the debates and discussions went on, as they must have on the bus and at work. The combination of those accents sounded like singing. Like some European choir of hard life, their song could have been “Come all ye faithful, whatever your faiths, for we are the world, we are the ones to make a brighter day.”

We weren’t allowed to finish with the papers until 7 o’clock so in winter, with all the sales and deliveries done, I’d head for the Workmen’s or Tabeners to read the paper and have a sarsaparilla in front of the fire. There was no shortage of advisers giving their version of life, politics, moneylenders, religion or war. The old pugs would say, “Always lead with your left, son.” Mentoring of children in mining towns probably goes back to the days when eight-year-olds worked down below. Some of their yarns would start with “When we was kids . . . “ I think that blokes then may have been more reliant on their mates than we are today. Three of my favourites were Eddie Pellizer, Len Wyhoon and a crusty old Scott called Sandy Dunbar. Ed Pellizer said, “You can learn something from even the biggest idiots.” They and many others spread the faith in humanity by leading exemplary lives.

It took me another two years to realise that most of the good men and women were either heathens or socialists and some were both. They believed it was the work you did, not the position you held that counted. Their message to us can be refined down to eight simple words: “We are all here to help one another.”

Pub blokes in those days were frank, fearless and no frills, confident about who we were and where we’d been. Some worked at the abattoirs, Cyclone and the cotton mills. There was the comic, the tragic and the legendary. Some were tough, gruff and surly, no doubt hurt by deprivation, war and hard physical work. There were some who had been taught from an early age that fighting with your fists was a necessary life skill; others were cheerful, kind and generous. The rest moved somewhere in between, depending on how things were going. I was called Mate, Sport, China, Magoo, Squire, Lad, Cobber, Paesan, Jock, Nugget, Sunshine, Bello, and Bastia, while some preferred not to speak at all. Forty years later, I asked Jim Donohue about one of these sad and humble “mutes”. Jim paused before answering. “The roof came down on his mate out at 20.” There’s an explanation for everything.

Nobody except Tom Gannon, the editor of The Powlett Express, dared questioned the Catholic priest who had warned us from the pulpit: “You’re not to have anything to do with that Joe Chambers.” Joe had spoken out against the war in Vietnam. By spring I was starting to doubt the Catholic three A’s: “Pray, Pay and Obey.” Tom would end up losing his newspaper.

Friday morning, 20th December, the day the Kirrak mine closed, was overcast. My mate Robert Legge and I rode our bikes out there. I thought about asking John Bordignon if he’d like to come but thought, “Naagh, he won’t be interested.”

At the mine I can remember an air of solemness, and apprehension about the future. Men were going to be out of work for the first time. I went into the engine room to watch the cable wound in. The inside of the engine room still had blackened timbers from the fire of 1964. There where several Italians on that last shift, but none of them seemed too concerned. A few joked around. I know for certain that some had seen and survived a lot worse in Europe.

When the last cage came up and the miners had walked away from it, someone yelled out “Have you locked it up, Harry?” We turned to look but Harry didn’t reply. Maybe he was lost for words.

I can remember some bloke scooped some helmets and all the time tokens off the board into a cardboard box. Someone gave a speech, thanking the workers. Some bloke gave me an old drill bit as a souvenir. The men from The Sun newspaper took some photos. When it was over, cars started to leave. A few men hung around in silence as if they’d just buried a good old mate and didn’t know what to say. Sometimes silence says a lot.

That was it. As we rode home for lunch, the sun came out. It would soon be summer and the sea would be starting to draw us out.

At about 5 o’clock, I was at the Workmen’s Club doing my last day of selling papers when the news went around town that Doc Sleeman had died.

The union blokes came up to the Workmen’s Club and got a couple of barrels of beer and set them up in the meeting room behind the Union Theatre, the room where so much had happened. Some of those miners stayed until it was very late. I reckon I would have too.