Measured in money, Henry Meyrick’s life was a miserable failure. His legacy is his words, which expose a dark chapter of Gippsland’s – and Victoria’s – history.

By Frank Coldebella

IN 2012 I was given an old book, Life in the Bush 1840-1847, that had been rescued from the dumpsters at the Wonthaggi Recyclers.

Written by F.J. Meyrick, it tells the story of the author’s uncle, Henry Meyrick, who was born in 1822 and who grew up in a vicarage in Ramsbury, Wiltshire, England.

Much of the book is based on letters Meyrick wrote home to his mother during his six years in Australia, ending in his death by drowning in Gippsland in 1847, aged just 25.

By Frank Coldebella

IN 2012 I was given an old book, Life in the Bush 1840-1847, that had been rescued from the dumpsters at the Wonthaggi Recyclers.

Written by F.J. Meyrick, it tells the story of the author’s uncle, Henry Meyrick, who was born in 1822 and who grew up in a vicarage in Ramsbury, Wiltshire, England.

Much of the book is based on letters Meyrick wrote home to his mother during his six years in Australia, ending in his death by drowning in Gippsland in 1847, aged just 25.

Henry was a quiet and reserved boy of good standing, excellent character and determination, well versed in the English and classical writers but with no great love for precise scholarship.

Life in the Bush (1840 – 1847): A Memoir of Henry Howard Meyrick by F.J. Meyrick, published London, Nelson, 1939

His father, a magistrate, a doctor of divinity, a farmer and sportsman, died when Henry was 17. His mother, a woman of great character, beauty and intelligence, had nine children and hence no time or inclination to nurse her sorrow as they had to leave the vicarage almost immediately for the next incumbent.

Young, inexperienced and with few skills, Henry and his cousin Alfred decided to seek their future in the booming colony of Port Phillip. Aged 19 and 17, they left with £1000 pound each and high hopes for adventures and fortunes to be made.

After a six-month voyage, they arrived in Melbourne in 1840 at the height of the boom. The population was just under 11,000. Speculators besieged the Land Office. Inns were crowded and everything was expensive. There were two banks and four newspapers, but there was no bridge over the Yarra, no roads and the town was knee-deep in mud.

Victoria did not yet exist so Melbourne was administered from Sydney. Salaries were paid to protectors of the blacks but the blacks were unprotected. In the Goulburn area and around Portland Bay, they were shot like dogs whenever they were met with. The Port Phillip Herald carried an advertisement from a property owner offering a reward of £50 for the capture of an Aboriginal leader called Jacky Jacky.

Unused to the concept of private property, an Aborigine was sentenced for theft. He boldly replied to the Justice of the Peace: “What for you say I steal? What for you steal my country? You big thief. Go back to your country and let black fellow alone.”

Meyrick’s judged the Aborigines a friendly race, poor and begging but very honest.

With the optimism and inexperience of youth, he and Alfred set to work farming sheep, with the assistance of an Aborigine called Yal Yal. Within a year the boom was finished and Melbourne was in a miserable state of depression. Cattle were almost valueless and there was an overproduction of sheep and wool.

Deciding “no man can thrive in this accursed” Westernport, early in 1846 they set off with the remainder of their sheep for Gippsland, accompanied by another Englishman, Pat Gannon, Yal Yal and another Aborigine. The going was hard and slow. They crossed the Bass River on February 12th and reached San Remo the next day. Heading for Tarwin, they crossed a creek which we call the Powlett and which Yal Yal called the Toolongoom. They arrived at the Tarwin River on February 20th.

With all its anxieties and hardships, this trek gave Henry the happiest three months of his six years in Australia, but he was haunted by some of the things he had seen along the way.

He had a delicate fear of giving anxiety to his mother so purposefully omitted his own losses and accidents in his letters home, but on arrival at Glenmaggie on April 11th he wrote to her: “We have learned some wisdom in Gippsland. It is a current saying that a man who has lived here can match the devil himself. It certainly is the most lawless place I have ever heard of.”

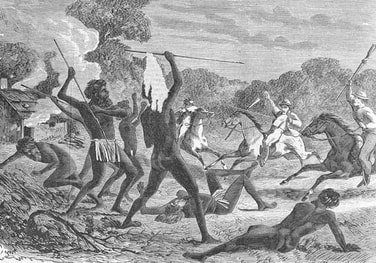

Most tellingly, he wrote of the cruelties of the settlers towards the blacks:

"... The blacks are very quiet here now, poor wretches. No wild beast of the forest was ever hunted down with such unsparing perseverance as they are. Men, women and children are shot whenever they can be met with. Some excuse might be found for shooting the men by those who are daily getting their cattle speared, but what they can urge in their excuse who shoot the women and children I cannot conceive.

“I have protested against it at every station I have been in Gippsland, in the strongest language, but these things are kept very secret as the penalty would certainly be hanging.

“... For myself, if I caught a black actually killing my sheep, I would shoot him with as little remorse as I would a wild dog, but no consideration on earth would induce me to ride into a camp and fire on them indiscriminately, as is the custom whenever the smoke is seen.

Life in the Bush (1840 – 1847): A Memoir of Henry Howard Meyrick by F.J. Meyrick, published London, Nelson, 1939

His father, a magistrate, a doctor of divinity, a farmer and sportsman, died when Henry was 17. His mother, a woman of great character, beauty and intelligence, had nine children and hence no time or inclination to nurse her sorrow as they had to leave the vicarage almost immediately for the next incumbent.

Young, inexperienced and with few skills, Henry and his cousin Alfred decided to seek their future in the booming colony of Port Phillip. Aged 19 and 17, they left with £1000 pound each and high hopes for adventures and fortunes to be made.

After a six-month voyage, they arrived in Melbourne in 1840 at the height of the boom. The population was just under 11,000. Speculators besieged the Land Office. Inns were crowded and everything was expensive. There were two banks and four newspapers, but there was no bridge over the Yarra, no roads and the town was knee-deep in mud.

Victoria did not yet exist so Melbourne was administered from Sydney. Salaries were paid to protectors of the blacks but the blacks were unprotected. In the Goulburn area and around Portland Bay, they were shot like dogs whenever they were met with. The Port Phillip Herald carried an advertisement from a property owner offering a reward of £50 for the capture of an Aboriginal leader called Jacky Jacky.

Unused to the concept of private property, an Aborigine was sentenced for theft. He boldly replied to the Justice of the Peace: “What for you say I steal? What for you steal my country? You big thief. Go back to your country and let black fellow alone.”

Meyrick’s judged the Aborigines a friendly race, poor and begging but very honest.

With the optimism and inexperience of youth, he and Alfred set to work farming sheep, with the assistance of an Aborigine called Yal Yal. Within a year the boom was finished and Melbourne was in a miserable state of depression. Cattle were almost valueless and there was an overproduction of sheep and wool.

Deciding “no man can thrive in this accursed” Westernport, early in 1846 they set off with the remainder of their sheep for Gippsland, accompanied by another Englishman, Pat Gannon, Yal Yal and another Aborigine. The going was hard and slow. They crossed the Bass River on February 12th and reached San Remo the next day. Heading for Tarwin, they crossed a creek which we call the Powlett and which Yal Yal called the Toolongoom. They arrived at the Tarwin River on February 20th.

With all its anxieties and hardships, this trek gave Henry the happiest three months of his six years in Australia, but he was haunted by some of the things he had seen along the way.

He had a delicate fear of giving anxiety to his mother so purposefully omitted his own losses and accidents in his letters home, but on arrival at Glenmaggie on April 11th he wrote to her: “We have learned some wisdom in Gippsland. It is a current saying that a man who has lived here can match the devil himself. It certainly is the most lawless place I have ever heard of.”

Most tellingly, he wrote of the cruelties of the settlers towards the blacks:

"... The blacks are very quiet here now, poor wretches. No wild beast of the forest was ever hunted down with such unsparing perseverance as they are. Men, women and children are shot whenever they can be met with. Some excuse might be found for shooting the men by those who are daily getting their cattle speared, but what they can urge in their excuse who shoot the women and children I cannot conceive.

“I have protested against it at every station I have been in Gippsland, in the strongest language, but these things are kept very secret as the penalty would certainly be hanging.

“... For myself, if I caught a black actually killing my sheep, I would shoot him with as little remorse as I would a wild dog, but no consideration on earth would induce me to ride into a camp and fire on them indiscriminately, as is the custom whenever the smoke is seen.

Aborigines and white settlers in battle. Samuel Calvert 27 May 1867. Print: wood engraving. State Library of Victoria pictures collection.

Aborigines and white settlers in battle. Samuel Calvert 27 May 1867. Print: wood engraving. State Library of Victoria pictures collection. “They [the Aborigines] will very shortly be extinct. It is impossible to say how many have been shot, but I am convinced that not less than 450 have been murdered altogether ..."

“I have heard tales told and some things I have seen that would form as dark a page as ever you would read in the book of history, but I thank god I have never participated in them.

“If I could remedy these things, I would speak loudly though it cost me all I am worth in the world, but as I cannot, I will keep aloof and know nothing and say nothing.”

After leaving Glenmaggie in May 1847, Meyrick and Alfred stayed with Mr Desailly and his wife, who was expecting a baby. When Mrs Desailly became seriously ill, Meyrick set off on a long ride to Alberton to fetch a doctor. He drowned trying to cross the swollen Thompson River.

F.J. Meyrick writes that Alfred and Yal Yal searched for Meyrick’s body for a fortnight, Yal Yal lamenting: “Away, away, when the sun rises we reach the river. We follow the torrent. It hurries on and on. We cry out where is the little master. Our eyes grow weary of the tumbling water. Away, away, we follow the river. We cannot find him. He was kind brother to black Yal Yal. His name is writ big in Yal Yal’s heart.”

Meyrick and Mrs Desailly were buried side by side on a dry hill about a quarter of a mile from the Thompson River, seven miles above the junction of that river and the Latrobe, and about two miles below the junction with the Macalister River.

Meyrick’s brother James wrote that he possessed the strongest common sense and clear judgement. “He never lost sight of his duties as a Christian. Night after night before bedtime, under pretence of seeing that the sheep were all right, he went out only to pray.”

Measured in money, Meyrick’s life was a miserable failure. Starting with £1000 and all the opportunities of a new country, he worked for six years, enduring continual privation and misfortune, disappointments and hardship. At the end of it all, there was just £500 left.

Yet his letters tell us his life was in no sense wasted. His courage never failed him and disappointment did not embitter him. He died fighting a torrent for the life of a woman and her unborn child. His is a story of gallant failure.

Like many courageous pioneers who perished in the bush or drowned in a flood after blazing a trail or clearing some bush, his efforts made it easier for the next and the next.

But his real legacy is his words, which expose a dark chapter of Gippsland’s – and Victoria's – history.

Life in the Bush (1840 – 1847): A Memoir of Henry Howard Meyrick by F.J. Meyrick, published London, Nelson, 1939

“I have heard tales told and some things I have seen that would form as dark a page as ever you would read in the book of history, but I thank god I have never participated in them.

“If I could remedy these things, I would speak loudly though it cost me all I am worth in the world, but as I cannot, I will keep aloof and know nothing and say nothing.”

After leaving Glenmaggie in May 1847, Meyrick and Alfred stayed with Mr Desailly and his wife, who was expecting a baby. When Mrs Desailly became seriously ill, Meyrick set off on a long ride to Alberton to fetch a doctor. He drowned trying to cross the swollen Thompson River.

F.J. Meyrick writes that Alfred and Yal Yal searched for Meyrick’s body for a fortnight, Yal Yal lamenting: “Away, away, when the sun rises we reach the river. We follow the torrent. It hurries on and on. We cry out where is the little master. Our eyes grow weary of the tumbling water. Away, away, we follow the river. We cannot find him. He was kind brother to black Yal Yal. His name is writ big in Yal Yal’s heart.”

Meyrick and Mrs Desailly were buried side by side on a dry hill about a quarter of a mile from the Thompson River, seven miles above the junction of that river and the Latrobe, and about two miles below the junction with the Macalister River.

Meyrick’s brother James wrote that he possessed the strongest common sense and clear judgement. “He never lost sight of his duties as a Christian. Night after night before bedtime, under pretence of seeing that the sheep were all right, he went out only to pray.”

Measured in money, Meyrick’s life was a miserable failure. Starting with £1000 and all the opportunities of a new country, he worked for six years, enduring continual privation and misfortune, disappointments and hardship. At the end of it all, there was just £500 left.

Yet his letters tell us his life was in no sense wasted. His courage never failed him and disappointment did not embitter him. He died fighting a torrent for the life of a woman and her unborn child. His is a story of gallant failure.

Like many courageous pioneers who perished in the bush or drowned in a flood after blazing a trail or clearing some bush, his efforts made it easier for the next and the next.

But his real legacy is his words, which expose a dark chapter of Gippsland’s – and Victoria's – history.

Life in the Bush (1840 – 1847): A Memoir of Henry Howard Meyrick by F.J. Meyrick, published London, Nelson, 1939