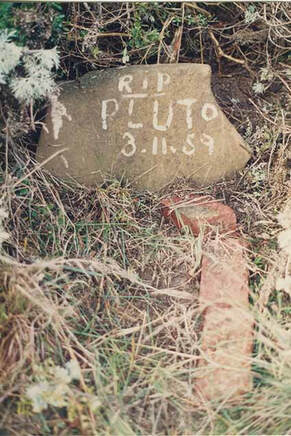

Jim McDonnell had a succession of dogs called Pluto.

Jim McDonnell had a succession of dogs called Pluto. Photo taken near Jim’s hut, 1980s.

THE mounds of shells dotted along the Bass Coast are evidence that these have been relaxing and bountiful gathering places for millennia. On meeting Australia’s original coast campers, Captain Cook noted “They live in a tranquillity … and are far more happier than we Europeans … They think themselves provided with all the necessarys of life … they seemed to set no value upon anything we gave them.”

During the Depression of the 1920s and 1930s many single men were forced to leave home to look for work or food. They camped wherever they could, including along the coast. One such was Jim McDonnell, who was still living in a hut on the coast between Harmers and Cape in the mid-1970s, preferring a moderate and harmonious life away from the noise, competition and trivia of town, attuned to nature’s positives.

His hut was in a well-chosen spot. It fitted snugly with a minimum of disturbance into a north-facing gully like a concealed bird’s nest, sheltered from the cold ocean wind by tea tree and banksias. On the edge of country where farmland, swamp, bush, creek and marine ecosystems meet, a short walk from what was then a very rough dead-end track called the Old Boiler Road, his hut evolved as materials became available or arrived by sea. He kept chooks, a small garden and a series of dogs, all called Pluto.

Jim’s mates came to stay and, when the weather was good, families camped nearby. There was a strong presence of union clans camped along this part of the coast, including the Cutlers, the Harmers, the McKells, the Norrises, the Longstaffs, the Bells, the Fosters and the Wilsons. Their inquiring and well-ordered minds were open to learning and ideas. Few believed in a god but they accepted any plain impious stranger as a potential mate. After working at the coalface in fumes and dust, they reckoned the sunlit colours, sounds and sea air were paradise enough. The waves washed away the coal dust and town stress. Perhaps a regular leisured pilgrimage to the beach was the original inspiration for baptism.

At a time when competition, gambling, alcohol and religion dominated town culture, the coast had its own priorities and rhythms influenced by weather, tide, winds, moon and season. There was a freedom from need in getting by with less. Fishing and coalmining both allow the brain to explore ideas and bring things up from the deep. Success lay in careful observation then doing the right thing. Coincidentally the earliest writers of the then revolutionary religion Christianity were also said to be fishermen.

Tom Gill was a teenager in the 1950s when he fell out with his father and headed for the beach with a tent. When the dark curtains of winter closed in, he moved in with Jim McDonnell. Both were cultural expatriates from beer, competition, conflict, TV and consumerism.

Jim worked at Kirrak mine and then for the railways doing track maintenance between Dalyston and Woolamai. He rode everywhere on a one-speed bike with upturned curly handlebars. We would see it parked outside his sister May’s place at 58 McBride Avenue, and he would wave when he passed us on his way to the beach.

Tom also rode a bicycle to work. His first job was at the mine, then he left to work on the night shift at the cotton mills as it allowed more time for fishing and other interests.

Over the decades Jim had acquired a thorough understanding of the seasonal ebb and flow of marine life as well as an intimate knowledge of concealed fish holes and submerged ledges between Wilsons Road and Cutlers beach. On a high tide, with no moon and little swell, they used a miner’s pit lamp and net to catch garfish, feeling with a toe near the rock edges lest they end up in the deep.

The combination of changes in seaweed, salt odours, avian activities and flowers hinted at the change of seasonal activity. After the spring tides when there was a midnight high tide they would set lines at low tide for gummy sharks and check them next morning. They caught crayfish with a hand line and net using a fish head or piece of abalone for bait. Surplus crays and fish could be exchanged for milk and other produce with the Cardamone family on Wilsons Road. For the calm days, Jim had built a fishing boat from wood collected on the beach.

With a few chooks, vegies, wild ducks and mountain trout in the nearby creek, they ate well from both land and sea. A cellar dug into the cliff face kept food cool. Beehives in fish boxes and hollow winter-flowering banksias provided abundant honey.

One of Jim’s mates who worked at Cottee’s jam factory in Melbourne would bring heaps of jam. “We couldn’t eat it all,” says Tom. “I’m sure there is still some buried out there.”

The hut was seven feet by 14 feet (2.1 metres by 4.2 metres). There were bees in the wall and a ship’s hatch served as a window shutter. After winter storms exposed the coal seam at the base of the cliff, they would dig the coal, bag it and cart it home. There was about four ton of coal stacked near the hut. They burnt half coal and half melaleuca roots.

Fox skins were nailed on the door to dry. They checked about 100 rabbit traps morning and night. Every month they sent a chaff bag of dried flattened fox and rabbit skins to Younghusbands, the skin merchants in Melbourne. “At times our living expenses were ten bob a week.”

Jim combed the ocean beaches wearing sand shoes tied with string. It was the days before shipping containers so “a big blow” could bring treasure. His “yard” was a miracle of supply, with masts, rigging, rope, beams, numerous planks, crates, floats, fishing gear, nautilus shells. On one timely occasion some good roofing iron washed up attached to part of a roof.

While the track was impassable over the wet months, Jim and Tom left their bikes at the Boyds’ place on Wilsons Road and trekked across the paddocks. For Jim, this was a “leisurely stroll” after his wartime treks in the New Guinea heat. He was weathered, wiry and still energetic, a survivor of depression, war and lost love. He spent most of his time outdoors.

Winters were hard but also a time of remote stillness that, with an adjusted outlook, could be cosy and enlightening. Days passed immersed in reflective routine, chores were done and things understood with few words. By meditative firelight and ocean churn, winter melancholy could produce insights, the clutter of life’s experience could be evaluated and understood. All the hut owners between the river and Eagles Nest had a humble shyness. An ecology of mind helped them to fit in, figure out, make do, and adapt to changing circumstances.

Surrounded by the beauty and power of nature, Jim was comfortable with what others would consider a hard life. He reminded me of a line from a poem called The Miller of the Dee in our primary school reader: “I envy no man and no man envies me.” I think of Jim when I hear the song Simple Ben. There is virtue in an unadorned life that gets its serenity from moderation and the capacity to be contented with little.

The last time I spoke to Jim was at Cutlers Rocks summer 75-76 he was slowing down but spoke of recovering some bricks from the wreck of the Artisan out at Harmers Haven. I don’t know if he ever did.

Fifty years later, Tom Gill recalled his years of living in a hut on the coast as “the best time of my life”.

After a few years in the hut, Tom had saved enough to buy a Triumph motorbike and a block on newly opened Viminaria Road in Harmers Haven, between Jock McLeod and Eddie Harmer. Eventually he moved back to Wonthaggi. But like many who have spent long, golden, carefree days at the coast during their teenage years, Tom’s experiences and insights from those years loomed large in his memory.

Fifty odd years later, sitting in his mansion in an upmarket neighbourhood, Tom told me, with a quavering voice, “It was the best time of my life.”

August 29, 2016

I loved reading this recall of life in this most special spot, thank you. I have been living in Harmer’s for the last 19 years and the feeling of living here hasn’t changed

Tricia Hogan, Harmers Haven