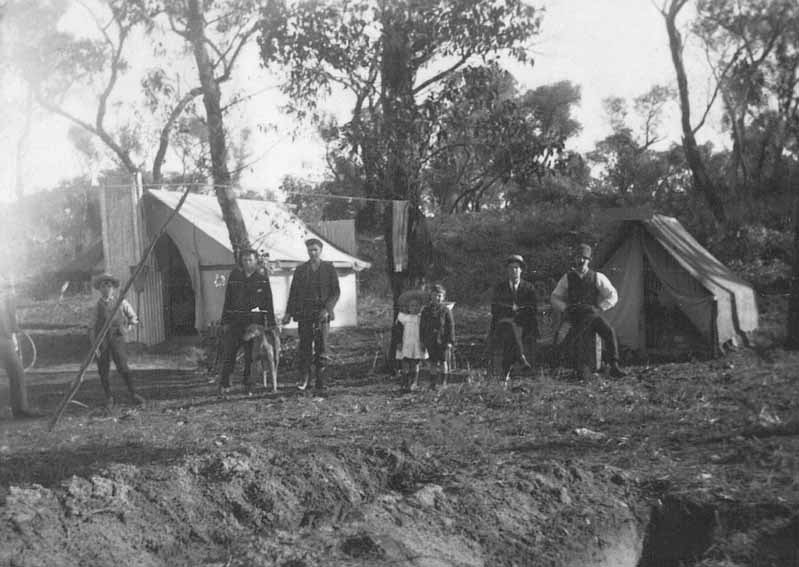

Tree planters camped with their families at Tank Hill while they planted 3000 street trees around Wonthaggi in the early 1910s.

Tree planters camped with their families at Tank Hill while they planted 3000 street trees around Wonthaggi in the early 1910s. Years after houses replaced Wonthaggi’s tent town, many old people remembered their camping times as the best days of their lives.

By Frank Coldebella

IN 1892 Australia was six separate colonies each with its own postage stamps and tax system. Ten years later, without a shot being fired or a battle fought, it was the most dynamic and democratic nation in the world.

How did this happen so far from the civilised world?

In his book Born in a Tent, Bill Garner suggests the camp is where some of our social progress originated and where we evolved our national ideal of a fair go.

Camping is the single defining experience of pioneering life that connected people to country.

When the first British fleet arrived in 1788, they had more than 600 tents. There were six convicts to a tent. Some were teenagers and children, the youngest a nine-year-old. Two years later most were still living under canvas.

In 1840 Paul Strzelecki and Charlie Tarra explored from NSW to what we now call Corner Inlet, to Corinella via Korumburra. They were immersed in the vegetation for weeks, camping at night, absorbing the sounds, smells and life of the forest.

By the end of the 1850s, camping was a common way of life. One-third of Victoria’s population – selectors, miners, shearers, drovers, bullock drivers, tree clearers, trappers, unemployed – were still camping. Camps are sorting places for ideas. They might even have the latest reading material to be passed around. Help and advice are easily exchanged at a campsite, as are collective family experiences, knowledge, history, ideas, successes and failures. A stranger arriving at a camp provided a new topic of conversation and news from other places.

Camping is a different way of domestic and social life. The transparency connects people to neighbours. We feel others’ pain and problems when they are close by. Away from town and with only the essentials of life, teamwork, self-regulation and the common good became the norm. People worked, ate, suffered and sang and laughed together, just as in our tribal evolutionary past.

In 1851 goldminers camped at Buninyong, near Ballarat, called a meeting to discuss the possibility of getting a fairer go. Over the next three years people had numerous small meetings around evening fires. Interpreters mined the multicultural knowledge, ideas and collective wisdom of thousands of people from 20 countries. Small meetings fed into big meetings which discussed the problems and potential of this rich, underutilised and mismanaged land.

Thousands of gatherings, discussions and debates culminated in the writing of the diggers’ charter which petitioned the governor for a fair tax, the right to vote and the right to own land. In 2006 this “Diggers Charter” was inducted into the UNESCO Memory of the World register of significant historical documents.

In 1870 the Gippsland forests were opened up for farming. The first settlers camped on their blocks until they had the resources to build a hut.

Forty years later, 800 workers, half with their families, camped alongside the railway line they were building from Nyora to Wonthaggi. Week after week, on the job and around the camp, they were close enough to speak to a dozen or more people. It was a very cold winter. When they camped at Kilcunda, there was snow on the beach. Clean water was in short supply, dysentery was rife. Isolated, cold, damp, sick, fearful, unable to afford medical care, campmates cared for one another.

The gold miners brought the spirit of Eureka to Wonthaggi, an isolated place with time and space around campfires and on the job to discuss the possibility that things could be done better. The opinions of the women who accompanied their husbands would have counted there. Shared hardship and responsibility must have boosted confidence in their ability to get things done. As the railway line progressed, campfire conversations evolved into the public conversation. This ethos became imbedded in Wonthaggi’s cultural activism, spurring the campaign for our communally funded hospital and health care system, possibly the first in the world. According to Professor Rae Frances, Wonthaggi was to become “a town that would punch above its weight in shaping twentieth century industrial relations in Australia”.

When it came time to disband the camp at Wonthaggi, people were very reluctant to go. Some had to be evicted. Years later, Arthur Heeney wrote that for many years in his youth (up to the 1920s) many people still lived in tents from Graham Street to the current Dudley campus.

Years later, many old people remembered their camping times as the best days of their lives, when the co-operative spirit became part of the town’s cultural mindset.

Once the town was established and families were separated by walls, I wonder if some missed the gang around the scented evening campfire and the yarns of fellow rovers. A writer to the Powlett Express in 1911 describes “the sleeping town as being “wrapt in sombre gloom”. Was he missing the camaraderie of the camp?

After a time of comfortable monotony, were they nostalgic for the rollercoaster of chaos, joy, sorrow and splendour when they and friends families slept on bracken beds while camped in the snow by the railway line? When the weather got warm and tea tree flowered, did they feel an urge to be out there waking to the chorus of birds singing and the fragrance of rain on eucalypt leaves?

Henry Lawson, who was born in a tent and spent most of his life camping, wrote:

They were hard old days, they were battling days;

they were cruel times but then, In spite of it all, we

shall live tonight in those hard old days again.

“Food tastes better if it’s cooked outside,” my boyhood neighbour Lavonia Coleman often said. She was born in 1881, and soundtrack of her memory included cicadas, crickets, frogs and birds.

During long, hot summers at Cape Paterson, away from the conventions of the town, old religious alliances faded for a few weeks as all were immersed in the spirit of beach and bush. The marriage of campers Joe Gilmour, a Catholic, and Annie Legg, from the Church of England, was a significant event in Wonthaggi’s social progress.

Some Wonthaggi clans still camp together every year just a few kilometres from home. One family has done so for five generations. Free of distraction, clutter and pressure, they become calm enough to do the mental housework necessary for a balanced and meaningful life.

Every coast needs camping areas where people of different backgrounds and beliefs can mingle and share ideas. The alternative is a monoculture of private real estate enclaves with too much of everything, including boredom.

In 1997 the state government proposed to reduce the number of campsites at Tidal River to make way for a commercial hotel. Richard Frankland, representing the local indigenous people, stood on a picnic table and said “It’s not about us looking at this land and seeing money. It’s about looking at this land and seeing culture.”

Like any campers, we are all here just for a while.

COMMENTS

March 14, 2016

Another wonderful edition of Post. Just love what Frank writes and boy can he write!

Anne Davie, Ventor

IN 1892 Australia was six separate colonies each with its own postage stamps and tax system. Ten years later, without a shot being fired or a battle fought, it was the most dynamic and democratic nation in the world.

How did this happen so far from the civilised world?

In his book Born in a Tent, Bill Garner suggests the camp is where some of our social progress originated and where we evolved our national ideal of a fair go.

Camping is the single defining experience of pioneering life that connected people to country.

When the first British fleet arrived in 1788, they had more than 600 tents. There were six convicts to a tent. Some were teenagers and children, the youngest a nine-year-old. Two years later most were still living under canvas.

In 1840 Paul Strzelecki and Charlie Tarra explored from NSW to what we now call Corner Inlet, to Corinella via Korumburra. They were immersed in the vegetation for weeks, camping at night, absorbing the sounds, smells and life of the forest.

By the end of the 1850s, camping was a common way of life. One-third of Victoria’s population – selectors, miners, shearers, drovers, bullock drivers, tree clearers, trappers, unemployed – were still camping. Camps are sorting places for ideas. They might even have the latest reading material to be passed around. Help and advice are easily exchanged at a campsite, as are collective family experiences, knowledge, history, ideas, successes and failures. A stranger arriving at a camp provided a new topic of conversation and news from other places.

Camping is a different way of domestic and social life. The transparency connects people to neighbours. We feel others’ pain and problems when they are close by. Away from town and with only the essentials of life, teamwork, self-regulation and the common good became the norm. People worked, ate, suffered and sang and laughed together, just as in our tribal evolutionary past.

In 1851 goldminers camped at Buninyong, near Ballarat, called a meeting to discuss the possibility of getting a fairer go. Over the next three years people had numerous small meetings around evening fires. Interpreters mined the multicultural knowledge, ideas and collective wisdom of thousands of people from 20 countries. Small meetings fed into big meetings which discussed the problems and potential of this rich, underutilised and mismanaged land.

Thousands of gatherings, discussions and debates culminated in the writing of the diggers’ charter which petitioned the governor for a fair tax, the right to vote and the right to own land. In 2006 this “Diggers Charter” was inducted into the UNESCO Memory of the World register of significant historical documents.

In 1870 the Gippsland forests were opened up for farming. The first settlers camped on their blocks until they had the resources to build a hut.

Forty years later, 800 workers, half with their families, camped alongside the railway line they were building from Nyora to Wonthaggi. Week after week, on the job and around the camp, they were close enough to speak to a dozen or more people. It was a very cold winter. When they camped at Kilcunda, there was snow on the beach. Clean water was in short supply, dysentery was rife. Isolated, cold, damp, sick, fearful, unable to afford medical care, campmates cared for one another.

The gold miners brought the spirit of Eureka to Wonthaggi, an isolated place with time and space around campfires and on the job to discuss the possibility that things could be done better. The opinions of the women who accompanied their husbands would have counted there. Shared hardship and responsibility must have boosted confidence in their ability to get things done. As the railway line progressed, campfire conversations evolved into the public conversation. This ethos became imbedded in Wonthaggi’s cultural activism, spurring the campaign for our communally funded hospital and health care system, possibly the first in the world. According to Professor Rae Frances, Wonthaggi was to become “a town that would punch above its weight in shaping twentieth century industrial relations in Australia”.

When it came time to disband the camp at Wonthaggi, people were very reluctant to go. Some had to be evicted. Years later, Arthur Heeney wrote that for many years in his youth (up to the 1920s) many people still lived in tents from Graham Street to the current Dudley campus.

Years later, many old people remembered their camping times as the best days of their lives, when the co-operative spirit became part of the town’s cultural mindset.

Once the town was established and families were separated by walls, I wonder if some missed the gang around the scented evening campfire and the yarns of fellow rovers. A writer to the Powlett Express in 1911 describes “the sleeping town as being “wrapt in sombre gloom”. Was he missing the camaraderie of the camp?

After a time of comfortable monotony, were they nostalgic for the rollercoaster of chaos, joy, sorrow and splendour when they and friends families slept on bracken beds while camped in the snow by the railway line? When the weather got warm and tea tree flowered, did they feel an urge to be out there waking to the chorus of birds singing and the fragrance of rain on eucalypt leaves?

Henry Lawson, who was born in a tent and spent most of his life camping, wrote:

They were hard old days, they were battling days;

they were cruel times but then, In spite of it all, we

shall live tonight in those hard old days again.

“Food tastes better if it’s cooked outside,” my boyhood neighbour Lavonia Coleman often said. She was born in 1881, and soundtrack of her memory included cicadas, crickets, frogs and birds.

During long, hot summers at Cape Paterson, away from the conventions of the town, old religious alliances faded for a few weeks as all were immersed in the spirit of beach and bush. The marriage of campers Joe Gilmour, a Catholic, and Annie Legg, from the Church of England, was a significant event in Wonthaggi’s social progress.

Some Wonthaggi clans still camp together every year just a few kilometres from home. One family has done so for five generations. Free of distraction, clutter and pressure, they become calm enough to do the mental housework necessary for a balanced and meaningful life.

Every coast needs camping areas where people of different backgrounds and beliefs can mingle and share ideas. The alternative is a monoculture of private real estate enclaves with too much of everything, including boredom.

In 1997 the state government proposed to reduce the number of campsites at Tidal River to make way for a commercial hotel. Richard Frankland, representing the local indigenous people, stood on a picnic table and said “It’s not about us looking at this land and seeing money. It’s about looking at this land and seeing culture.”

Like any campers, we are all here just for a while.

COMMENTS

March 14, 2016

Another wonderful edition of Post. Just love what Frank writes and boy can he write!

Anne Davie, Ventor