Chelle Destefano invites her hearing audience to enter her world.

Chelle Destefano invites her hearing audience to enter her world. By Geoff Ellis

HALF way through an Auslan poetry recital, Chelle Destefano gestures like an erupting volcano. That's her answer to "What does Kapow look like in Auslan?"

"Like in Batman?" she is asked.

Chelle has come to Bass Coast Adult Learning’s life skills class to teach us about Auslan poetry and to share Deaf culture. Through her on-line interpreter, she explains that she saw a lot of TV when she was a kid. She did watch Batman but was intrigued by a show about the boy who could fly. She didn't understand why he flew or the full storyline as there were no subtitles, no words for Chelle.

HALF way through an Auslan poetry recital, Chelle Destefano gestures like an erupting volcano. That's her answer to "What does Kapow look like in Auslan?"

"Like in Batman?" she is asked.

Chelle has come to Bass Coast Adult Learning’s life skills class to teach us about Auslan poetry and to share Deaf culture. Through her on-line interpreter, she explains that she saw a lot of TV when she was a kid. She did watch Batman but was intrigued by a show about the boy who could fly. She didn't understand why he flew or the full storyline as there were no subtitles, no words for Chelle.

Born deaf, Chelle was denied language until she was 15. She tries not to be negative, though it's easy to imagine that she'd be further down her chosen path if she'd been empowered with sign language at an earlier age. "The education system was half good, half bad. I had to find a way to express myself."

She still doesn't talk much. "It's too hard for people to understand what I say. I write things down a lot."

At school, Chelle was taught not to aim high. "Deaf people don't feel empowered.” She was told she would never make a living from art as the careers adviser bundled her into a science course.

Eventually she escaped to Adelaide to follow her passion. Since she completed her Bachelor of visual art in 2006, her talent has been recognised around the world with many exhibitions and a long list of awards.

Chelle’s paintings and illustrations of ghosts, old buildings and a little yellow beetle car called Taxi continue to delight. She has painted Taxi in many situations including going to a carnival, climbing stairs, gathering with dogs, eating easter eggs and going to Italy and meeting a tuk tuk and falling in love. An art book of his adventures will be released soon.

She still doesn't talk much. "It's too hard for people to understand what I say. I write things down a lot."

At school, Chelle was taught not to aim high. "Deaf people don't feel empowered.” She was told she would never make a living from art as the careers adviser bundled her into a science course.

Eventually she escaped to Adelaide to follow her passion. Since she completed her Bachelor of visual art in 2006, her talent has been recognised around the world with many exhibitions and a long list of awards.

Chelle’s paintings and illustrations of ghosts, old buildings and a little yellow beetle car called Taxi continue to delight. She has painted Taxi in many situations including going to a carnival, climbing stairs, gathering with dogs, eating easter eggs and going to Italy and meeting a tuk tuk and falling in love. An art book of his adventures will be released soon.

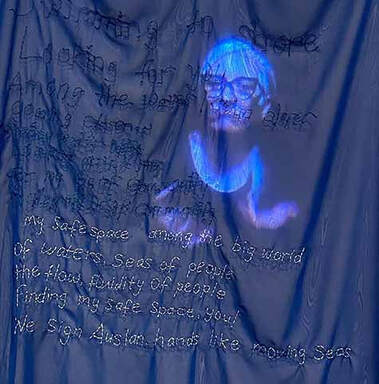

Navigating to Safe Space, a prize-winning work in which Chelle showed what it was like for a deaf person to live in a hearing world.

Navigating to Safe Space, a prize-winning work in which Chelle showed what it was like for a deaf person to live in a hearing world. From visual art, her work is evolving into performance art and Auslan poetry. She talks about winning the inaugural Lake Art Prize this year with her work Navigating to Safe Space, in which a poem about deaf safe space and deaf community is projected onto a piece of blue material. She used blue thread for the words as a way of showing what it is like to lipread, and how fatigued you become after concentrating for 10 minutes.

As it happened, the audio wasn’t working but Chelle later realised it was a good thing. "I wanted to give the Judges the full deaf experience!” she says. “They had to really concentrate on my piece."

She prepares to perform another beautiful poem. It's about living on the spectrum and forming relationships. Chelle's interpreter listens to the author read it and translates it for Chelle who then takes it to another level. Part mime, part expressive intuition, her performance unfolds from the Auslan signing and flows out to us like a gentle tide. She uses body movements to provide rhythm, meter and volume. Facial and hand gestures add nuance. Words fail to describe her performance of those emotions and I guess that's the point. Hearing people need to accommodate deafness and cross modality from our proscribed world. As an example, Chelle talks about the bushfires where deaf people had limited access to information that was crucial for their own safety.

Chelle performed four poems by other people as she opened the door into Deaf culture. She's a willing ambassador who loves the interface between all cultures. The presentation has to end somewhere but Chelle is doing what she loves - providing the opportunity for deaf people to have a voice.

Does the boy who could fly still puzzle her? "That penny finally dropped when I saw the subtitled version." Thirty years too late; now we understand, much more.

Chelle mentions she is doing a powerful Deaf project collaboration with Claire Bridge, a hearing person who comes from a Deaf family (her grandparents were Deaf and her mother's first language was Auslan. Claire was also an interpreter previously). They have established a collaborative Deaf community project called What I Wish I’d Told You, an immersive projection installation exhibition which centres Deaf voices, identity and culture, with stories by over 45 Deaf storytellers.) 'What I Wish I’d Told You' celebrates and affirms Deafhood. It will be exhibited in major public galleries in 2022. Keep your eyes out for exhibition dates at chelledestefano.com/.

As it happened, the audio wasn’t working but Chelle later realised it was a good thing. "I wanted to give the Judges the full deaf experience!” she says. “They had to really concentrate on my piece."

She prepares to perform another beautiful poem. It's about living on the spectrum and forming relationships. Chelle's interpreter listens to the author read it and translates it for Chelle who then takes it to another level. Part mime, part expressive intuition, her performance unfolds from the Auslan signing and flows out to us like a gentle tide. She uses body movements to provide rhythm, meter and volume. Facial and hand gestures add nuance. Words fail to describe her performance of those emotions and I guess that's the point. Hearing people need to accommodate deafness and cross modality from our proscribed world. As an example, Chelle talks about the bushfires where deaf people had limited access to information that was crucial for their own safety.

Chelle performed four poems by other people as she opened the door into Deaf culture. She's a willing ambassador who loves the interface between all cultures. The presentation has to end somewhere but Chelle is doing what she loves - providing the opportunity for deaf people to have a voice.

Does the boy who could fly still puzzle her? "That penny finally dropped when I saw the subtitled version." Thirty years too late; now we understand, much more.

Chelle mentions she is doing a powerful Deaf project collaboration with Claire Bridge, a hearing person who comes from a Deaf family (her grandparents were Deaf and her mother's first language was Auslan. Claire was also an interpreter previously). They have established a collaborative Deaf community project called What I Wish I’d Told You, an immersive projection installation exhibition which centres Deaf voices, identity and culture, with stories by over 45 Deaf storytellers.) 'What I Wish I’d Told You' celebrates and affirms Deafhood. It will be exhibited in major public galleries in 2022. Keep your eyes out for exhibition dates at chelledestefano.com/.