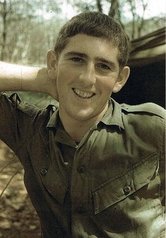

Tom Loughridge, 1969

Tom Loughridge, 1969 They left for Vietnam as boys and returned a year later as battle-scarred men. Gill Heal reports on one man's experience of trying to settle back into a life of farming and footy.

By Gill Heal

TOM Loughridge was 20 when the Loch Football Club flew him back from Singleton Army Base for the 1967 grand final.

They had a battle on their hands. Their foe, Inverloch-Kongwak, hadn’t been beaten all year. The arena, the Wonthaggi Football Ground, was lush with the gore of countless footy grand finals. But at 20, growing in speed and strength, dodging, weaving, containing his opponent, Tom was up for the challenge. As was his team.

The Korumburra Times reported that Loughridge had seven kicks for the first quarter and in the last minutes of the game the Loch men came from behind to slay the dragon, take the spoils and walk like gods among their own.

Tom missed all the back slapping. By 5am the next day he was back at Singleton. By March the following year the national serviceman was in Vietnam.

One month in, the way this newly-married young shearer understood the world shifted forever. A series of moments in his first operation emerged in nightmarish relief from the sweat and mud and booby traps and noise to blast away the bedrock of his life. His first exchange of fire brought the cold shock of understanding: that he could die here, that the future he had never questioned ─ Sue, some kids, a farm, Saturdays down at the oval ─ could be obliterated in an instant. “It had never entered my mind before.”

A second moment. Tom, a machine gunner, had been relieved on gun duty by two of his mates. He was lying beside them when a mortar hit a tree behind their gun position and his mates were thrown aside. In the chaos, his instincts at war with his training, the army won. He manned the gun and left the men lying there. He’d known them since Puckapunyal. He stayed with the gun as a dust-off helicopter came in to evacuate the dead and injured. “That image will stay with me forever. All the training in the world couldn’t prepare me for what had just happened. To see your mates wounded or killed and feeling so helpless ...” And the unbidden thought: “It could have been me.”

Later, a full-scale battle raged around them. In torrential rain with lightning so bright you could see the enemy in the distance, mortars, artillery guns, gunships, snoopy ─ the red line tracer coming from high in the sky ─ supported the infantry. They’d lit hexamine stoves to guide in a rocket-fuelled helicopter and help it to identify their positions. When a corner stove was extinguished by heavy rain, the gunship came through, firing, between their pits.

On a clearing patrol later that day, they discovered big numbers of enemy dead. A bulldozer was brought in to excavate a large grave. “Not a job for the faint-hearted,” he says in retrospect. More than Vietnamese bodies were buried that day. The words that might have described the horror were buried too.

Tom served 339 days in Vietnam. He knows the number down to the hour.

By the time they were discharged in February 1969, opposition to the Vietnam War was widespread. He’d gone not understanding what the war was about; he returned an agent of the nation’s shame, an object of loathing.

“When we were discharged, we all went in different directions. We’d been told to disappear, to make ourselves invisible to avoid hecklers. There was no plane ticket home from Sydney, just a second class train ticket.” Nor, when he got home, were there the traditional welcome home parties.

The worst was the unbridgeable gap in understanding. “My father asked me to give a talk on my war experiences. As though I’d been on a world trip!”

With the bewilderment came deepening anger. It wasn’t just the injustice of the ballot. “We went away as boys but when we came back we were old. The kids we grew up with were still kids. We came back hardened men. The fun had been squeezed out of you.”

The loss of their birth right, the 21st birthday party, was keenly felt. That public acknowledgement of manhood, the acceptance of the young adult into a close and welcoming community, was a ritual denied them.

Tom says he was lucky. He had someone to come home to. He’d intended to go back to shearing, to consolidate, put some savings behind them. But he couldn’t face being away from home again and instead became a share farmer. He’d had malaria twice in Vietnam. Now he had it again. He returned briefly to football but he wasn’t a hundred per cent and there wasn’t a lot of encouragement at the club.

By the first Vietnam Moratorium in May 1970, when 200,000 people across Australia marched to a mighty crescendo of anti-war conviction, Tom was a workaholic. “I had to work long hours so I could sleep at night. I just thought it was normal so I got on with it. You worked in isolation as much as possible so no-one could challenge you or ask you questions.”

In this way he and his veteran mates internalised the war they’d left behind and warred within themselves for decades, for many to the point of complete self-destruction. It’s a wonder, the courage and loyalty that has enabled couples like Sue and Tom to emerge strong and resilient.

I was one of those who marched down Bourke Street that day in 1970, more than a little impressed by my right thinking and political courage. Now, over 40 years later, Tom and Sue are my neighbours. I wonder about the magnitude of the untold, unseen losses associated with war. But most of all, I wonder at the suffering on a massive scale that we can choose not to see.

TOM Loughridge was 20 when the Loch Football Club flew him back from Singleton Army Base for the 1967 grand final.

They had a battle on their hands. Their foe, Inverloch-Kongwak, hadn’t been beaten all year. The arena, the Wonthaggi Football Ground, was lush with the gore of countless footy grand finals. But at 20, growing in speed and strength, dodging, weaving, containing his opponent, Tom was up for the challenge. As was his team.

The Korumburra Times reported that Loughridge had seven kicks for the first quarter and in the last minutes of the game the Loch men came from behind to slay the dragon, take the spoils and walk like gods among their own.

Tom missed all the back slapping. By 5am the next day he was back at Singleton. By March the following year the national serviceman was in Vietnam.

One month in, the way this newly-married young shearer understood the world shifted forever. A series of moments in his first operation emerged in nightmarish relief from the sweat and mud and booby traps and noise to blast away the bedrock of his life. His first exchange of fire brought the cold shock of understanding: that he could die here, that the future he had never questioned ─ Sue, some kids, a farm, Saturdays down at the oval ─ could be obliterated in an instant. “It had never entered my mind before.”

A second moment. Tom, a machine gunner, had been relieved on gun duty by two of his mates. He was lying beside them when a mortar hit a tree behind their gun position and his mates were thrown aside. In the chaos, his instincts at war with his training, the army won. He manned the gun and left the men lying there. He’d known them since Puckapunyal. He stayed with the gun as a dust-off helicopter came in to evacuate the dead and injured. “That image will stay with me forever. All the training in the world couldn’t prepare me for what had just happened. To see your mates wounded or killed and feeling so helpless ...” And the unbidden thought: “It could have been me.”

Later, a full-scale battle raged around them. In torrential rain with lightning so bright you could see the enemy in the distance, mortars, artillery guns, gunships, snoopy ─ the red line tracer coming from high in the sky ─ supported the infantry. They’d lit hexamine stoves to guide in a rocket-fuelled helicopter and help it to identify their positions. When a corner stove was extinguished by heavy rain, the gunship came through, firing, between their pits.

On a clearing patrol later that day, they discovered big numbers of enemy dead. A bulldozer was brought in to excavate a large grave. “Not a job for the faint-hearted,” he says in retrospect. More than Vietnamese bodies were buried that day. The words that might have described the horror were buried too.

Tom served 339 days in Vietnam. He knows the number down to the hour.

By the time they were discharged in February 1969, opposition to the Vietnam War was widespread. He’d gone not understanding what the war was about; he returned an agent of the nation’s shame, an object of loathing.

“When we were discharged, we all went in different directions. We’d been told to disappear, to make ourselves invisible to avoid hecklers. There was no plane ticket home from Sydney, just a second class train ticket.” Nor, when he got home, were there the traditional welcome home parties.

The worst was the unbridgeable gap in understanding. “My father asked me to give a talk on my war experiences. As though I’d been on a world trip!”

With the bewilderment came deepening anger. It wasn’t just the injustice of the ballot. “We went away as boys but when we came back we were old. The kids we grew up with were still kids. We came back hardened men. The fun had been squeezed out of you.”

The loss of their birth right, the 21st birthday party, was keenly felt. That public acknowledgement of manhood, the acceptance of the young adult into a close and welcoming community, was a ritual denied them.

Tom says he was lucky. He had someone to come home to. He’d intended to go back to shearing, to consolidate, put some savings behind them. But he couldn’t face being away from home again and instead became a share farmer. He’d had malaria twice in Vietnam. Now he had it again. He returned briefly to football but he wasn’t a hundred per cent and there wasn’t a lot of encouragement at the club.

By the first Vietnam Moratorium in May 1970, when 200,000 people across Australia marched to a mighty crescendo of anti-war conviction, Tom was a workaholic. “I had to work long hours so I could sleep at night. I just thought it was normal so I got on with it. You worked in isolation as much as possible so no-one could challenge you or ask you questions.”

In this way he and his veteran mates internalised the war they’d left behind and warred within themselves for decades, for many to the point of complete self-destruction. It’s a wonder, the courage and loyalty that has enabled couples like Sue and Tom to emerge strong and resilient.

I was one of those who marched down Bourke Street that day in 1970, more than a little impressed by my right thinking and political courage. Now, over 40 years later, Tom and Sue are my neighbours. I wonder about the magnitude of the untold, unseen losses associated with war. But most of all, I wonder at the suffering on a massive scale that we can choose not to see.