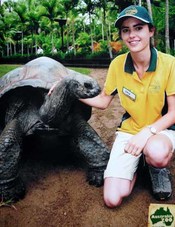

Jaquelina Alves Ferreira at Australia Zoo

Jaquelina Alves Ferreira at Australia Zoo Taking a year away from study between school and university is sometimes seen as a slightly dangerous diversion. GILL HEAL spoke to five local students who followed their own paths and found unexpected benefits

LAST year, Jaquelina Alves-Ferreira was writing essays on wildlife conservation at Wonthaggi Secondary College. Today she’s in South Africa, volunteering on a project that protects the rhinoceros from poachers.

Back home in Wonthaggi, Jarrod Donohue works on building sites, an apprentice carpenter. Stephen Loftus travels to Melbourne for classes in dancing, singing and acting, juggles rehearsals for two major musicals and works part time.

Each of these three is deferring from university studies. Each is capitalising on different opportunities.

These Bass Coast students are not alone. These days more than one in four school-leavers decide to take this gap year.

Jaquelina Alves Ferreira at Australia Zoo

Many of them do so to get a job and save – more than half, according to a 2012 report released by the National Centre for Vocational Education and Research. One in 10 is like Jarrod Donohue and enrols in full-time study for a non-university qualification.

Jarrod expects the experience of working on site to help during his mechanical engineering studies. “You get a feel for what it’s like to work full time,” he says. Taking a gap year will also give him time to confirm that he’s made the right career choice. There are also the practical carpentry skills. “At the end of the day there’s a sense of satisfaction. I feel like – even if in the end it’s not right – it’s been really worthwhile.”

Back home in Wonthaggi, Jarrod Donohue works on building sites, an apprentice carpenter. Stephen Loftus travels to Melbourne for classes in dancing, singing and acting, juggles rehearsals for two major musicals and works part time.

Each of these three is deferring from university studies. Each is capitalising on different opportunities.

These Bass Coast students are not alone. These days more than one in four school-leavers decide to take this gap year.

Jaquelina Alves Ferreira at Australia Zoo

Many of them do so to get a job and save – more than half, according to a 2012 report released by the National Centre for Vocational Education and Research. One in 10 is like Jarrod Donohue and enrols in full-time study for a non-university qualification.

Jarrod expects the experience of working on site to help during his mechanical engineering studies. “You get a feel for what it’s like to work full time,” he says. Taking a gap year will also give him time to confirm that he’s made the right career choice. There are also the practical carpentry skills. “At the end of the day there’s a sense of satisfaction. I feel like – even if in the end it’s not right – it’s been really worthwhile.”

Jacqueline Wheeler: trumpeter in the Wonthaggi Citizens Band.

When Jacqueline Wheeler completed Year 12 in Wonthaggi in 2013 she wasn’t ready to go to Melbourne. She didn’t have a drivers’ licence but more importantly she knew she was more comfortable in a rural environment. She belonged to the Wonthaggi Citizen’s Band. She was connected. “For me,” she says, “the thought of living so far away from where I grew up was daunting.” Some of her friends have deferred for the same reason.

Wonthaggi career counsellor Jack Taylor says people have a perception that things go wrong when kids don’t go straight on to study but it’s not so. The gap year offers time to develop more self knowledge. The drop-out rate of students who go straight to uni is high. “Rural school kids have this burning ambition to get to the city. Once there, they often find the city’s not for them.”

Jacqueline Wheeler’s approach is incremental. Last year she enrolled in an online primary teaching course. “The support was helpful,” she says. “You could work at your own speed.” This year she’s working at Woolworths and saving for 2016 when she plans to move to Melbourne to do a bachelor of education course at Monash University’s Berwick campus.

When Jacqueline Wheeler completed Year 12 in Wonthaggi in 2013 she wasn’t ready to go to Melbourne. She didn’t have a drivers’ licence but more importantly she knew she was more comfortable in a rural environment. She belonged to the Wonthaggi Citizen’s Band. She was connected. “For me,” she says, “the thought of living so far away from where I grew up was daunting.” Some of her friends have deferred for the same reason.

Wonthaggi career counsellor Jack Taylor says people have a perception that things go wrong when kids don’t go straight on to study but it’s not so. The gap year offers time to develop more self knowledge. The drop-out rate of students who go straight to uni is high. “Rural school kids have this burning ambition to get to the city. Once there, they often find the city’s not for them.”

Jacqueline Wheeler’s approach is incremental. Last year she enrolled in an online primary teaching course. “The support was helpful,” she says. “You could work at your own speed.” This year she’s working at Woolworths and saving for 2016 when she plans to move to Melbourne to do a bachelor of education course at Monash University’s Berwick campus.

Stephen Loftus has no doubts about what he wants to do: it’s a bachelor of fine arts (music theatre) at the Victorian College of the Arts. Over 500 applicants compete for 20 places in this course. Hence his focus on developing his performance skills: the once-weekly sessions at the VCA and the mad rehearsal schedule that comes of being in two major musicals simultaneously: Wonthaggi's Pippin and Leongatha’s Gypsy. That involves some sensitive negotiation with the directors. Plus there are the various full-time and part-time jobs that help him save for next year.

He thinks he’s made the right decision and will be in a strong position to win a place. “I’d rather be too busy than not busy enough,” he says. “Everything is going to plan.”

Students who take the year off mature enormously in 12 months, says Jack Taylor; they’re far more independent, financially and otherwise, more sure of what they want to do. Anecdotally, he says, the evidence is that there’s far less chance of dropping out.

Researchers at the University of Sydney confirm this view although they concede that a gap year does not suit everyone. ''For many students, a gap year is about crystallising their decision-making, developing self-directed and self-regulation skills, broadening their competencies and self-organisation,'' says Professor Andrew Martin. The research found the general abilities developed in the gap year were more useful at university than at high school, where there was more supervision and guidance.

Clearly, a gap year worked brilliantly for Newhaven College students sisters Jacinta and Annie Cox, who travelled broadly after leaving school. As a volunteer, Jacinta was placed by Projects Abroad with host families in Argentina and Peru. She loved the culture so much that when she got back she transferred from science to arts, majoring in Spanish.

Annie’s gap year was less structured. She started by travelling through China, Hong Kong and Russia with her parents, then had a month in France learning French. She travelled with a friend through France and Southern Italy teaching English to different families and backpacked in Spain, Morocco, Germany, Turkey and South East Asia.

Looking back, Annie freely admits that travel is tiring. She got homesick. It’s hard coming back at the end of the day to a suitcase. “You long for your own place.” But at the same time, she says, travel teaches you so much, not just about different cultures but about yourself. “It’s not textbook learning. It’s a year of learning about your own limitations, what’s important to yourself, how to get on with others. I became more independent, learnt how to cook!"

When she came back she picked up the course she’d deferred from – medicine - and started French studies.

''Parents fear a gap year may disrupt a student's momentum, but it is possible it is part of the momentum,'' Professor Martin says

If momentum’s the thing, you’d have to say that Jaquelina Alves Ferreira is on a roll. On track to become an environmental scientist and animal biologist, she trawled the internet for volunteer placement opportunities and planned carefully. (“You must plan in advance,” she says. “You have to book ahead for these things. You have to know where you’re going, what course you want to do when you get back. You can lose your way if you don’t.”)

She began the year at the iconic Australia Zoo and was impressed to see its global reach – that the funds raised by the zoo’s tiger show, for instance, help to pay the rangers who protect the Sumatran tiger from poachers.

Today she’s on the last of three placements in South Africa’s Zululand region, volunteering with Wildlife ACT in South Africa, an organisation that works for the preservation of wildlife and protection against poaching. From there she'll fly to Seychelles to work on a project monitoring sea turtles. She’ll be coming home at the end of June.

In the meantime, she’s squared off with fear and uncertainty. She’s learned to live without hot water, electricity and the internet. She’s become a resourceful contributor to different households. She’s been a team person, a learner mentored by experts but equally passionate and committed.

Recently Jaquelina told her father, Ricardo: "I remember being told: ‘Eat your food because there are children in Africa that would love to have your food!’ Or ‘be happy that you can go to school because children in Africa would love to go to school but there isn't a school for them to go to’. Now I understand. I would love that my friend saw these kids walking miles to get to school and they have no shoes".

Incalculable learning, says her dad. The dawning realisation of one’s luck or wealth.

He thinks he’s made the right decision and will be in a strong position to win a place. “I’d rather be too busy than not busy enough,” he says. “Everything is going to plan.”

Students who take the year off mature enormously in 12 months, says Jack Taylor; they’re far more independent, financially and otherwise, more sure of what they want to do. Anecdotally, he says, the evidence is that there’s far less chance of dropping out.

Researchers at the University of Sydney confirm this view although they concede that a gap year does not suit everyone. ''For many students, a gap year is about crystallising their decision-making, developing self-directed and self-regulation skills, broadening their competencies and self-organisation,'' says Professor Andrew Martin. The research found the general abilities developed in the gap year were more useful at university than at high school, where there was more supervision and guidance.

Clearly, a gap year worked brilliantly for Newhaven College students sisters Jacinta and Annie Cox, who travelled broadly after leaving school. As a volunteer, Jacinta was placed by Projects Abroad with host families in Argentina and Peru. She loved the culture so much that when she got back she transferred from science to arts, majoring in Spanish.

Annie’s gap year was less structured. She started by travelling through China, Hong Kong and Russia with her parents, then had a month in France learning French. She travelled with a friend through France and Southern Italy teaching English to different families and backpacked in Spain, Morocco, Germany, Turkey and South East Asia.

Looking back, Annie freely admits that travel is tiring. She got homesick. It’s hard coming back at the end of the day to a suitcase. “You long for your own place.” But at the same time, she says, travel teaches you so much, not just about different cultures but about yourself. “It’s not textbook learning. It’s a year of learning about your own limitations, what’s important to yourself, how to get on with others. I became more independent, learnt how to cook!"

When she came back she picked up the course she’d deferred from – medicine - and started French studies.

''Parents fear a gap year may disrupt a student's momentum, but it is possible it is part of the momentum,'' Professor Martin says

If momentum’s the thing, you’d have to say that Jaquelina Alves Ferreira is on a roll. On track to become an environmental scientist and animal biologist, she trawled the internet for volunteer placement opportunities and planned carefully. (“You must plan in advance,” she says. “You have to book ahead for these things. You have to know where you’re going, what course you want to do when you get back. You can lose your way if you don’t.”)

She began the year at the iconic Australia Zoo and was impressed to see its global reach – that the funds raised by the zoo’s tiger show, for instance, help to pay the rangers who protect the Sumatran tiger from poachers.

Today she’s on the last of three placements in South Africa’s Zululand region, volunteering with Wildlife ACT in South Africa, an organisation that works for the preservation of wildlife and protection against poaching. From there she'll fly to Seychelles to work on a project monitoring sea turtles. She’ll be coming home at the end of June.

In the meantime, she’s squared off with fear and uncertainty. She’s learned to live without hot water, electricity and the internet. She’s become a resourceful contributor to different households. She’s been a team person, a learner mentored by experts but equally passionate and committed.

Recently Jaquelina told her father, Ricardo: "I remember being told: ‘Eat your food because there are children in Africa that would love to have your food!’ Or ‘be happy that you can go to school because children in Africa would love to go to school but there isn't a school for them to go to’. Now I understand. I would love that my friend saw these kids walking miles to get to school and they have no shoes".

Incalculable learning, says her dad. The dawning realisation of one’s luck or wealth.