After a lifetime of biochemical research, Dick Wettenhall is now mastering the mysteries of soil, yeast and oak. GILL HEAL meets the prize-winning vigneron.

By Gill Heal

IF YOU took Dick Wettenhall at his word, you’d believe that his successes were all about luck. It explains his distinguished academic career and the mounting tally of medals for wines from his Grantville and Gurdies vineyards. “Right place, right time,” he’d say.

Born at Sale, Dick was two months old when his father died. His mother took him back to Rosedale where her brother was running the family farm. The next four years were deeply formative. His uncle was a free spirit with scant respect for conventional boundaries. Young Dick adored him. It’s where he learnt to be an independent thinker and self-starter. Aged four, he was driving tractors. Bit of luck there.

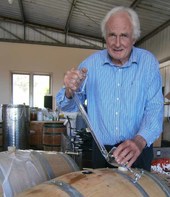

Dick Wettenhall in his Gurdies wineroom.

That year his mother remarried and they moved to Melbourne but most of his relatives lived on the land and he never lost his links with farm life. Not being “academic”, Dick had always assumed that he would become a farmer but his expectations were dashed when his older brother won family backing first. His stepfather imported spices, nuts and other food additives, so in the expectation of working in the business, a heavy-hearted teenager began a science degree. When it emerged that he had little interest in the business but was fascinated by science, his stepfather, “a fine man”, encouraged him to stay on at uni.

Eventually he became a biochemist. Today, Dick Wettenhall’s name is particularly associated with ground-breaking research identifying proteins, mediators of the actions of insulin on cells, as well as cell abnormalities that lead to the uncontrolled growth we call cancer.

Professor Wettenhall was appointed head of Melbourne University’s Russell Grimwade School of Biochemistry in 1989. At a time when there was a growing understanding of the importance of multidisciplinary approaches to research, Dick and his colleague, Professor Richard Larkins, led The University of Melbourne’s participation in the Bio21 Cluster, in partnership with the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute and The Royal Melbourne Hospital.

With senior colleagues, Dick proposed that the university make a major investment in a new multidisciplinary research institute to be known as the Bio21 Institute to serve as the flagship of the Bio21 Cluster. The total cost would be $104.5 million. Seed money was duly contributed. “Just luck really,” Dick says.

When the dream materialised, they had a seven-storey building that would eventually house 500 researchers and post-graduate students and up to 15 research and industry organisations, including the entire Melbourne-based research division of CSL, Australia’s largest biopharmaceutical company. “Its grand purpose,” Dick says, “was to combine research, business, laboratories and equipment in order to discover new medical, agricultural and environmental diagnostics and candidate drugs and insecticides for treating diseases. Research with the potential for commercialisation.”

After seven years as interim/founding director of the institute, Dick retired and found his way to the Gurdies.

He had always intended to retire to a farm but he didn’t like killing animals and was looking for an alternative. One of the key people in the Institute was researching the biological warfare that goes on within vines – understanding which insects were destructive pests and which were beneficial. Another colleague was an expert in soil, researching what was going on underground.

Dick bought a cow paddock in Grantville and started to read. He went to every clearing sale under the sun and snapped up a 10-year supply of viticulture magazines for $30. Most of what he read wasn’t transferable to South Gippsland conditions but it gave him a language he could begin to use. He had a four-acre laboratory and collegial support. Paradise on earth.

His first plantings on his Grantville paddock were half-starved things. His soil analysis – does night follow day? – confirmed that the top two layers, which set like a brick in summer, were entirely lacking in nutrients. The next layer was clay, which releases acidic aluminium toxic to vines. The third was penetrable, moist, sandy soil. Next thing he was seen digging rows of trenches. “Trenches?” the neighbours chortled. “Mad professor!”

“The results were spectacular,” Dick confesses happily. The trenching assisted soil improvement with lime, gypsum, organic matter and other nutrients and the new plantings developed deep roots. Today few things give him greater satisfaction than those robust, relatively drought-resistant vines.

He’s become addicted to viticulture and has developed his own guidelines for growing grapes. He’s not an organic grower but he’ll tell you to avoid using pesticides unless absolutely necessary. “Use nature,” he’ll say. Ladybirds kill harmful mites. “See a ladybird and you’ll know the mites are under control.” Understand how to use chemicals selectively. Unless you have a major infestation of caterpillars, you might not need to use insecticides at all. He prefers copper and sulphur as preventative fungicides as they are relatively benign. “If mildew forms on the outside of the leaf, spraying with a preventive chemical can prevent invasion of the grape tissue.”

Four years ago, Dick expanded his operation with the purchase of the Gurdies Winery. One of the oldest vineyards in the region, it came with wine-making capability and a glorious view over the northern reaches of Western Port. Unsurprisingly, his transition from grape grower to wine maker was made easier by his background as a biochemist but he is grateful for his good fortune in meeting a highly regarded vigneron, Marcus Satchel, who mentored him through his first vintage as a winemaker. As for the view, time for that later.

Marcus admires Dick’s inquiring, scientific approach. “He bought one of the oldest vineyards in South Gippsland growing varieties that suit the climate. He’s put enormous effort into improving the vineyard: improving the soil, eradicating disease. So he starts with a good base product.”

Embracing Marcus’s dictum “that good wines are made in the vineyard”, Dick won a silver medal for tempranillo wine made from his first harvest of grapes from his Grantville vineyard. “His Grantville block is a success against the odds,” says Marcus. “People said he’d never grow grapes on it but it’s become a very successful patch of dirt. It’s that combination of good farming and science. He has a dab hand for it.”

The partnership has been fruitful. After a lifetime wedded to micro measurement, the laboratory scientist has learnt the pleasure of the macro measurement of grape fermentation. But there’s art too, says Marcus. Initiated into the arcane mysteries of yeast and oak, Dick has gained recognition as an industry player. “I’ve been lucky enough to win a couple of medals” he’ll say.

His main success has been at the Gippsland Wine Show where, over the past three years, his shiraz, merlot, tempranillo and riesling and blends of verdelho/chardonnay and cabernet merlot have won medals. One of his most satisfying results has been a gold medal for merlot at the recent Rutherglen Wine Show. In the case of the Gurdies vineyard, an enormous effort has been required to overcome problems with the vines and eliminate disease. This was particularly challenging during Dick’s first season, 2011, notable for its sustained wet weather and described by many as the worst season on record for producing grapes.

“Welcome to Gippsland,” Marcus would say.

That was the year the mad professor won his first two medals.

IF YOU took Dick Wettenhall at his word, you’d believe that his successes were all about luck. It explains his distinguished academic career and the mounting tally of medals for wines from his Grantville and Gurdies vineyards. “Right place, right time,” he’d say.

Born at Sale, Dick was two months old when his father died. His mother took him back to Rosedale where her brother was running the family farm. The next four years were deeply formative. His uncle was a free spirit with scant respect for conventional boundaries. Young Dick adored him. It’s where he learnt to be an independent thinker and self-starter. Aged four, he was driving tractors. Bit of luck there.

Dick Wettenhall in his Gurdies wineroom.

That year his mother remarried and they moved to Melbourne but most of his relatives lived on the land and he never lost his links with farm life. Not being “academic”, Dick had always assumed that he would become a farmer but his expectations were dashed when his older brother won family backing first. His stepfather imported spices, nuts and other food additives, so in the expectation of working in the business, a heavy-hearted teenager began a science degree. When it emerged that he had little interest in the business but was fascinated by science, his stepfather, “a fine man”, encouraged him to stay on at uni.

Eventually he became a biochemist. Today, Dick Wettenhall’s name is particularly associated with ground-breaking research identifying proteins, mediators of the actions of insulin on cells, as well as cell abnormalities that lead to the uncontrolled growth we call cancer.

Professor Wettenhall was appointed head of Melbourne University’s Russell Grimwade School of Biochemistry in 1989. At a time when there was a growing understanding of the importance of multidisciplinary approaches to research, Dick and his colleague, Professor Richard Larkins, led The University of Melbourne’s participation in the Bio21 Cluster, in partnership with the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute and The Royal Melbourne Hospital.

With senior colleagues, Dick proposed that the university make a major investment in a new multidisciplinary research institute to be known as the Bio21 Institute to serve as the flagship of the Bio21 Cluster. The total cost would be $104.5 million. Seed money was duly contributed. “Just luck really,” Dick says.

When the dream materialised, they had a seven-storey building that would eventually house 500 researchers and post-graduate students and up to 15 research and industry organisations, including the entire Melbourne-based research division of CSL, Australia’s largest biopharmaceutical company. “Its grand purpose,” Dick says, “was to combine research, business, laboratories and equipment in order to discover new medical, agricultural and environmental diagnostics and candidate drugs and insecticides for treating diseases. Research with the potential for commercialisation.”

After seven years as interim/founding director of the institute, Dick retired and found his way to the Gurdies.

He had always intended to retire to a farm but he didn’t like killing animals and was looking for an alternative. One of the key people in the Institute was researching the biological warfare that goes on within vines – understanding which insects were destructive pests and which were beneficial. Another colleague was an expert in soil, researching what was going on underground.

Dick bought a cow paddock in Grantville and started to read. He went to every clearing sale under the sun and snapped up a 10-year supply of viticulture magazines for $30. Most of what he read wasn’t transferable to South Gippsland conditions but it gave him a language he could begin to use. He had a four-acre laboratory and collegial support. Paradise on earth.

His first plantings on his Grantville paddock were half-starved things. His soil analysis – does night follow day? – confirmed that the top two layers, which set like a brick in summer, were entirely lacking in nutrients. The next layer was clay, which releases acidic aluminium toxic to vines. The third was penetrable, moist, sandy soil. Next thing he was seen digging rows of trenches. “Trenches?” the neighbours chortled. “Mad professor!”

“The results were spectacular,” Dick confesses happily. The trenching assisted soil improvement with lime, gypsum, organic matter and other nutrients and the new plantings developed deep roots. Today few things give him greater satisfaction than those robust, relatively drought-resistant vines.

He’s become addicted to viticulture and has developed his own guidelines for growing grapes. He’s not an organic grower but he’ll tell you to avoid using pesticides unless absolutely necessary. “Use nature,” he’ll say. Ladybirds kill harmful mites. “See a ladybird and you’ll know the mites are under control.” Understand how to use chemicals selectively. Unless you have a major infestation of caterpillars, you might not need to use insecticides at all. He prefers copper and sulphur as preventative fungicides as they are relatively benign. “If mildew forms on the outside of the leaf, spraying with a preventive chemical can prevent invasion of the grape tissue.”

Four years ago, Dick expanded his operation with the purchase of the Gurdies Winery. One of the oldest vineyards in the region, it came with wine-making capability and a glorious view over the northern reaches of Western Port. Unsurprisingly, his transition from grape grower to wine maker was made easier by his background as a biochemist but he is grateful for his good fortune in meeting a highly regarded vigneron, Marcus Satchel, who mentored him through his first vintage as a winemaker. As for the view, time for that later.

Marcus admires Dick’s inquiring, scientific approach. “He bought one of the oldest vineyards in South Gippsland growing varieties that suit the climate. He’s put enormous effort into improving the vineyard: improving the soil, eradicating disease. So he starts with a good base product.”

Embracing Marcus’s dictum “that good wines are made in the vineyard”, Dick won a silver medal for tempranillo wine made from his first harvest of grapes from his Grantville vineyard. “His Grantville block is a success against the odds,” says Marcus. “People said he’d never grow grapes on it but it’s become a very successful patch of dirt. It’s that combination of good farming and science. He has a dab hand for it.”

The partnership has been fruitful. After a lifetime wedded to micro measurement, the laboratory scientist has learnt the pleasure of the macro measurement of grape fermentation. But there’s art too, says Marcus. Initiated into the arcane mysteries of yeast and oak, Dick has gained recognition as an industry player. “I’ve been lucky enough to win a couple of medals” he’ll say.

His main success has been at the Gippsland Wine Show where, over the past three years, his shiraz, merlot, tempranillo and riesling and blends of verdelho/chardonnay and cabernet merlot have won medals. One of his most satisfying results has been a gold medal for merlot at the recent Rutherglen Wine Show. In the case of the Gurdies vineyard, an enormous effort has been required to overcome problems with the vines and eliminate disease. This was particularly challenging during Dick’s first season, 2011, notable for its sustained wet weather and described by many as the worst season on record for producing grapes.

“Welcome to Gippsland,” Marcus would say.

That was the year the mad professor won his first two medals.