Hartley Tobin

Hartley Tobin Meryl and Hartley Tobin’s passions are very different, but they both bring a meticulous approach to their subjects.

By Gill Heal

BEST not to leave the car at the gate when you call on Meryl and Hartley Tobin. Not if you’re in a hurry. Their drive is 300 metres long. Lined with stands of banksia and other carefully cultivated natives, it meanders down to The Gurdies home they’ve lived in and worked from for almost 30 years.

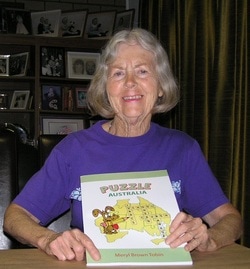

Work is the operative word here. Meryl Tobin has just had four puzzle books published. This is in addition to 14 books and hundreds of poems and puzzles, scores of short stories, travel and other articles and some cartoons published in more than 150 magazines and newspapers in Australia and internationally.

In some ways you’re not really a writer until you’re out there and published, she says. She began early. Aged eight, Meryl Brown was sending jokes (not original ones, she confesses ) to the Junior Age, then a newspaper page that featured children’s contributions and competitions.

“The family didn’t have a lot of money to spare but my dad always found money for stamps and envelopes.” Her appreciation of his support was the reason she eventually changed her professional name to Meryl Brown Tobin.

She was always writing. As she matured, she focused increasingly on social justice issues. Her first published short story was about a Vietnamese woman caught up in a war beyond her control. “I try not to be didactic but I do have a message.”

As a young mother, it distressed her to see evidence of any children suffering; she wanted all children to have the same opportunities. She wrote a lot of letters to The Age.

“I know what got me going!” she suddenly recalls. It was a story in The Age about how some Anglican bishops had written to then prime minister Robert Menzies saying there should be free and fair elections in Vietnam and Menzies had confessed their letter had kept him awake at night. “If Anglican bishops can have that kind of impact,” she decided, “I should be able to do something too.”

A teacher of English and history for many years, she loves order, word patterns and solving mysteries. Around 1975, Ashton Scholastic book clubs published her first four puzzle books. In total almost 300,000 were sold.

During the 1970s, she and Hartley made two trips around Australia. “It’s what got me going professionally,” she says. Hartley’s deep interest in plants was pivotal. Her articles were peppered with observations of local flora. They’d do their research before they left so they knew what to look for at different places. “She didn’t have to rush to a library,” Hartley says. “Her reference material was right there in the car beside her.”

The Age and The Sun published her pieces and travel writing became her bread and butter.

Hartley had done a mature age degree majoring in botany. One of his assignments required the study of a native plant. He already had an interest in banksias and was growing coastal banksias from seed. They were weekending at Coronet Bay where banksias grow along the shore. A lot of people have a broad knowledge of plants, he says, but very few really specialise. “As far as I know, mine was the first detailed record of the general life cycle of the coastal banksia.”

In 1979 they bought 13 acres at the foot of The Gurdies Nature Reserve on the Western Port shoreline. On it was an old sand dune ideal for growing banksias. Hartley’s appointment as principal of Bass Valley Primary School meant they could live there permanently and pursue his interest seriously. At one stage he had 36 species growing on the property.

In middle age – she was learning to pick her battles – Meryl became the publicity officer of the Bass Valley and District branch of the South Gippsland Conservation Society. After every meeting she sent a press release to the Sentinel Times. Her industry is prodigious. “I write submissions on everything that interests me; it can take me up to three months. I don’t just toss them off.”

But the rewards are great. “There’s always something new to learn,” Hartley says . “You get a lot of joy from seeing a plant flower for the first time. You think, Ah, I’ve got it to this stage!”

But there’s pain as well as pleasure. Most banksias flourish in dry conditions. Last year’s inundating rains killed big patches of mature trees. “Back to square one,” he says and shrugs. “The special ones come and go.”

For years he was the go-to man when an expert opinion on banksias was needed; these days he’s “eased back on giving talks” and has turned his attention to wood turning, but the much-loved coastal garden goes on inspiring thought and work.

“We’ll keep going while the energy’s there,” Hartley says.

BEST not to leave the car at the gate when you call on Meryl and Hartley Tobin. Not if you’re in a hurry. Their drive is 300 metres long. Lined with stands of banksia and other carefully cultivated natives, it meanders down to The Gurdies home they’ve lived in and worked from for almost 30 years.

Work is the operative word here. Meryl Tobin has just had four puzzle books published. This is in addition to 14 books and hundreds of poems and puzzles, scores of short stories, travel and other articles and some cartoons published in more than 150 magazines and newspapers in Australia and internationally.

In some ways you’re not really a writer until you’re out there and published, she says. She began early. Aged eight, Meryl Brown was sending jokes (not original ones, she confesses ) to the Junior Age, then a newspaper page that featured children’s contributions and competitions.

“The family didn’t have a lot of money to spare but my dad always found money for stamps and envelopes.” Her appreciation of his support was the reason she eventually changed her professional name to Meryl Brown Tobin.

She was always writing. As she matured, she focused increasingly on social justice issues. Her first published short story was about a Vietnamese woman caught up in a war beyond her control. “I try not to be didactic but I do have a message.”

As a young mother, it distressed her to see evidence of any children suffering; she wanted all children to have the same opportunities. She wrote a lot of letters to The Age.

“I know what got me going!” she suddenly recalls. It was a story in The Age about how some Anglican bishops had written to then prime minister Robert Menzies saying there should be free and fair elections in Vietnam and Menzies had confessed their letter had kept him awake at night. “If Anglican bishops can have that kind of impact,” she decided, “I should be able to do something too.”

A teacher of English and history for many years, she loves order, word patterns and solving mysteries. Around 1975, Ashton Scholastic book clubs published her first four puzzle books. In total almost 300,000 were sold.

During the 1970s, she and Hartley made two trips around Australia. “It’s what got me going professionally,” she says. Hartley’s deep interest in plants was pivotal. Her articles were peppered with observations of local flora. They’d do their research before they left so they knew what to look for at different places. “She didn’t have to rush to a library,” Hartley says. “Her reference material was right there in the car beside her.”

The Age and The Sun published her pieces and travel writing became her bread and butter.

Hartley had done a mature age degree majoring in botany. One of his assignments required the study of a native plant. He already had an interest in banksias and was growing coastal banksias from seed. They were weekending at Coronet Bay where banksias grow along the shore. A lot of people have a broad knowledge of plants, he says, but very few really specialise. “As far as I know, mine was the first detailed record of the general life cycle of the coastal banksia.”

In 1979 they bought 13 acres at the foot of The Gurdies Nature Reserve on the Western Port shoreline. On it was an old sand dune ideal for growing banksias. Hartley’s appointment as principal of Bass Valley Primary School meant they could live there permanently and pursue his interest seriously. At one stage he had 36 species growing on the property.

In middle age – she was learning to pick her battles – Meryl became the publicity officer of the Bass Valley and District branch of the South Gippsland Conservation Society. After every meeting she sent a press release to the Sentinel Times. Her industry is prodigious. “I write submissions on everything that interests me; it can take me up to three months. I don’t just toss them off.”

But the rewards are great. “There’s always something new to learn,” Hartley says . “You get a lot of joy from seeing a plant flower for the first time. You think, Ah, I’ve got it to this stage!”

But there’s pain as well as pleasure. Most banksias flourish in dry conditions. Last year’s inundating rains killed big patches of mature trees. “Back to square one,” he says and shrugs. “The special ones come and go.”

For years he was the go-to man when an expert opinion on banksias was needed; these days he’s “eased back on giving talks” and has turned his attention to wood turning, but the much-loved coastal garden goes on inspiring thought and work.

“We’ll keep going while the energy’s there,” Hartley says.