There is a tide in the affairs of man, Shakespeare reckoned, and you only get one chance to catch it. Liz Alger was determined not to miss her chance.

By Gill Heal

KORUMBURRA’S Coal Creek is full of stories about early settlement and mining. We didn’t expect stories of tall ships, though, until we came across Liz Alger, volunteering behind the counter at Devlin’s General Store.

Liz Alger can’t explain her affinity with tall ships. No-one in the family has had any nautical interest. She remembers watching The Onedin Line on the telly. “I loved that when I was a kid,” she confesses. “I lived for Sunday nights. I think I was a sailor in a past life”

Whatever the explanation, when the door to her tall ships romance opened, she walked through it, and through the next and the next. And she was transformed because of it.

Liz was working as a graphic artist, sharing a studio with her friend, Trish Hart, when a publisher asked her to illustrate a story of a ship. It was pre-Google. She borrowed every book she could to get a handle on the subject. “That’s when this strange thing happened. I’d get these shivers up my spine. I’d feel so stirred. These four-masted barques seemed so perfect, so beautiful. It’s something about balance: the height of the masts, the length of the hull, the wind-filled sails.”

Soon after, they started to see ads in the paper for tall ship experiences. “Wouldn’t that be amazing?” Liz always said, until finally Trish responded: “Stop saying that. Do something!” That was the start of it all. The Swedish barquentine, the Amorina, here for the First Fleet re-enactment, was taking on trainees. They booked on the leg from Melbourne to Portland via King Island. “I got really sick but we had good strong winds from the right direction and, being big and stable, it was the perfect ship to start on,” says Liz. The rawest of trainees, they hauled the lines and braced the yard and had a little time at the helm. By the time she went ashore in Portland, Liz was hooked.

The following year, they sailed from Sydney to Fiji on the Soren Larsen. A wooden ship, it rolled a lot, and Liz got sick again but her course was set. She became a volunteer on the Polly Woodside, read a lot and became a tour guide. She came to love the ship for its functionality: its ability to carry a big cargo in the most dangerous seas in the world, voyage after voyage, using just the power of the wind. “Those sailing ships were some of the most beautiful man-made objects ever made,” she claims.

She was learning about the ship all the time. The Polly Woodside was moored permanently on the Yarra but “working aloft, keeping everything oiled and functioning, made me realise how efficient she was.” Liz loved using the sailors’ tools, perfected over the centuries, and was enthralled by the stories told by a couple of old sailors who had worked on the famous German fleet of four- and five-masted barques known as the “Flying P-Liners”. When she could, she passed on their stories. She came to understand something of the “horribly hard” and addictive simplicity of the sailor’s life and the truth of Joseph Conrad’s claim that “the true peace of God begins a thousand miles from land”.

Liz had been terrified the first few times she went aloft. “Your knuckles are white, your heart is pounding. There are places on the rigging where you’re upside down. It’s the adrenalin rush; being very frightened is exciting. When you get down, all you want to do is go up again.” On the Polly Woodside she consolidated her skills and grew in confidence. She was ready for the high seas.

The two friends knew about two big four-masted barques, German ships that had passed to the Russians after World War II. One of these was the Kruzenshtern, “the most beautiful ship in the world”. Originally a Flying P-Liner and, after the Sedov, the largest sailing vessel still in operation, it was the last engine-less sailing ship ever built. Prior to WWII it had made 15 trips to Australia carrying wheat. This was the tall ship on which they pinned their hopes.

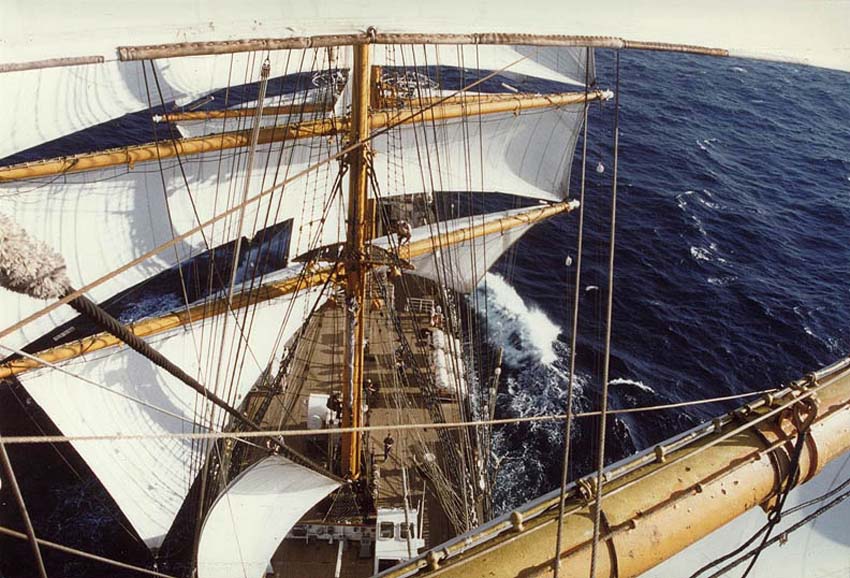

The Kruzenshtern in full sail off Fremantle

It wasn’t easy. They wrote a lot of letters, phoned Moscow, tried to speak to people. It was the time of the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s voyage to America. A huge, multi-legged regatta had been organised. They were told the Kruzenshtern wasn’t sailing but they could sail on the Sedov instead. They booked on the Tenerife to Puerto Rico leg and flew out to Tenerife. Seeing the Sedov’s masts for the first time, they were knocked sideways: “Oh, she was so huge!” They were intoxicated by the sights and sounds around them, the largest fleet of tall ships since the Napoleonic wars. The Young Endeavour was there, the Soren Larsen. “We had friends on board both of them.” They introduced themselves on board the Sedov. No-one could speak English; the cooking smells coming up from the galley were truly awful. They said: “Oh my God, what are we doing??”

As they were walking back along the wharf, they caught sight of a tiny shape on the horizon. Rooted to the spot they thought, “Could it be...?” A shift in angle confirmed four masts. It had to be the Kruzenshtern. Enthralled, they watched it all the way into the harbour. They were smitten.

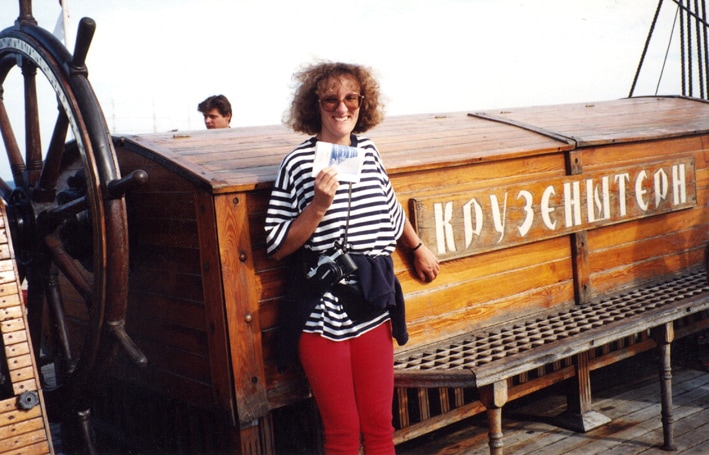

Dream ride: Liz Alger finds it difficult to hide the satisfaction after finally boarding the Kruzenshternin Tenerife.On board the Sedov, they experienced the massing of all those amazing tall ships for the race start and the crossing of the Atlantic. They couldn’t believe how fast the Sedov was.

“We lived with the Russian boys; ate with them, worked aloft with them,” says Liz. “Being told you can’t do something spurs you on to do amazing things aloft.”

Unbelievably, at Puerto Rico on a brief tour of the Kruzenshtern, they were offered a place with the crew on the last leg to New York. They had to decline. They had flights booked for the US and Europe and almost no spending money. But then they told themselves, life is not a dress rehearsal. Many phone calls, cancellations and calls on parents’ bank accounts later, they sailed out of Puerto Rico on the Kruzenshtern.

“Everybody on board loved that ship so much,” says Liz. “There was something magical about her. She’s got so much charisma.” They sailed past Bermuda through a Force 10 gale and the whole fleet sailed together up the Hudson on July 4.

In the years that followed, Liz and Trish tried to keep track of the Kruzenshtern but news was hard to get. Her future was looking bleak and there was a possibility she might never sail again. But a gift from the German Government of 11 million deutschmarks (about A$7 million) had her sailing again, still under a Russian flag.

Then in 1996 they heard the ship was to circumnavigate the globe to celebrate her 70th birthday. “We tried to get them to come to Melbourne; we wrote to Canberra; we worked really hard on the idea of hosting a visit,” says Liz ruefully. But the only planned port of call was Fremantle and the ship wasn’t taking on any foreigners. So they jumped on a plane to Perth, found that no-one seemed to know about the ship, persuaded the pilot to take them on his boat, and drawing alongside the ship, created their own personal welcoming party, waving madly all the while to Mamikon, the bosun.

Inveigling permission to crew on the next leg to Capetown, the two women combed the local op shops for work clothes, madly rang the local media to build some interest in the ship and were interviewed on radio.

The voyage across the Indian Ocean with big swells rolling up from the Atlantic was unforgettable. “The ship just powered along. It was so exhilarating. The feeling of speed, knowing it’s all happening just with the free and clean energy of the wind. You look up at the bridge and the officers are all there with big grins. Every single person is feeling it.”

They hit a Force 11 gale just before the Cape of Good Hope. They two of them were told later it is one of the most dangerous coasts in the world. You get holes in the sea. The water beneath you drops away just as a wave comes over the top. “We loved it,” says Liz. Tossed about in all this sky and sea and howling wind, they saw storm petrels, albatrosses... “It was just wonderful.”

Liz likes Joseph Conrad’s thoughts on this. He says sailing is like being on your own planet; on it is everything you need. You are a little self-contained world sailing across an amazing universe.

“It’s hard to become a normal person after experiencing that,” she says.

KORUMBURRA’S Coal Creek is full of stories about early settlement and mining. We didn’t expect stories of tall ships, though, until we came across Liz Alger, volunteering behind the counter at Devlin’s General Store.

Liz Alger can’t explain her affinity with tall ships. No-one in the family has had any nautical interest. She remembers watching The Onedin Line on the telly. “I loved that when I was a kid,” she confesses. “I lived for Sunday nights. I think I was a sailor in a past life”

Whatever the explanation, when the door to her tall ships romance opened, she walked through it, and through the next and the next. And she was transformed because of it.

Liz was working as a graphic artist, sharing a studio with her friend, Trish Hart, when a publisher asked her to illustrate a story of a ship. It was pre-Google. She borrowed every book she could to get a handle on the subject. “That’s when this strange thing happened. I’d get these shivers up my spine. I’d feel so stirred. These four-masted barques seemed so perfect, so beautiful. It’s something about balance: the height of the masts, the length of the hull, the wind-filled sails.”

Soon after, they started to see ads in the paper for tall ship experiences. “Wouldn’t that be amazing?” Liz always said, until finally Trish responded: “Stop saying that. Do something!” That was the start of it all. The Swedish barquentine, the Amorina, here for the First Fleet re-enactment, was taking on trainees. They booked on the leg from Melbourne to Portland via King Island. “I got really sick but we had good strong winds from the right direction and, being big and stable, it was the perfect ship to start on,” says Liz. The rawest of trainees, they hauled the lines and braced the yard and had a little time at the helm. By the time she went ashore in Portland, Liz was hooked.

The following year, they sailed from Sydney to Fiji on the Soren Larsen. A wooden ship, it rolled a lot, and Liz got sick again but her course was set. She became a volunteer on the Polly Woodside, read a lot and became a tour guide. She came to love the ship for its functionality: its ability to carry a big cargo in the most dangerous seas in the world, voyage after voyage, using just the power of the wind. “Those sailing ships were some of the most beautiful man-made objects ever made,” she claims.

She was learning about the ship all the time. The Polly Woodside was moored permanently on the Yarra but “working aloft, keeping everything oiled and functioning, made me realise how efficient she was.” Liz loved using the sailors’ tools, perfected over the centuries, and was enthralled by the stories told by a couple of old sailors who had worked on the famous German fleet of four- and five-masted barques known as the “Flying P-Liners”. When she could, she passed on their stories. She came to understand something of the “horribly hard” and addictive simplicity of the sailor’s life and the truth of Joseph Conrad’s claim that “the true peace of God begins a thousand miles from land”.

Liz had been terrified the first few times she went aloft. “Your knuckles are white, your heart is pounding. There are places on the rigging where you’re upside down. It’s the adrenalin rush; being very frightened is exciting. When you get down, all you want to do is go up again.” On the Polly Woodside she consolidated her skills and grew in confidence. She was ready for the high seas.

The two friends knew about two big four-masted barques, German ships that had passed to the Russians after World War II. One of these was the Kruzenshtern, “the most beautiful ship in the world”. Originally a Flying P-Liner and, after the Sedov, the largest sailing vessel still in operation, it was the last engine-less sailing ship ever built. Prior to WWII it had made 15 trips to Australia carrying wheat. This was the tall ship on which they pinned their hopes.

The Kruzenshtern in full sail off Fremantle

It wasn’t easy. They wrote a lot of letters, phoned Moscow, tried to speak to people. It was the time of the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s voyage to America. A huge, multi-legged regatta had been organised. They were told the Kruzenshtern wasn’t sailing but they could sail on the Sedov instead. They booked on the Tenerife to Puerto Rico leg and flew out to Tenerife. Seeing the Sedov’s masts for the first time, they were knocked sideways: “Oh, she was so huge!” They were intoxicated by the sights and sounds around them, the largest fleet of tall ships since the Napoleonic wars. The Young Endeavour was there, the Soren Larsen. “We had friends on board both of them.” They introduced themselves on board the Sedov. No-one could speak English; the cooking smells coming up from the galley were truly awful. They said: “Oh my God, what are we doing??”

As they were walking back along the wharf, they caught sight of a tiny shape on the horizon. Rooted to the spot they thought, “Could it be...?” A shift in angle confirmed four masts. It had to be the Kruzenshtern. Enthralled, they watched it all the way into the harbour. They were smitten.

Dream ride: Liz Alger finds it difficult to hide the satisfaction after finally boarding the Kruzenshternin Tenerife.On board the Sedov, they experienced the massing of all those amazing tall ships for the race start and the crossing of the Atlantic. They couldn’t believe how fast the Sedov was.

“We lived with the Russian boys; ate with them, worked aloft with them,” says Liz. “Being told you can’t do something spurs you on to do amazing things aloft.”

Unbelievably, at Puerto Rico on a brief tour of the Kruzenshtern, they were offered a place with the crew on the last leg to New York. They had to decline. They had flights booked for the US and Europe and almost no spending money. But then they told themselves, life is not a dress rehearsal. Many phone calls, cancellations and calls on parents’ bank accounts later, they sailed out of Puerto Rico on the Kruzenshtern.

“Everybody on board loved that ship so much,” says Liz. “There was something magical about her. She’s got so much charisma.” They sailed past Bermuda through a Force 10 gale and the whole fleet sailed together up the Hudson on July 4.

In the years that followed, Liz and Trish tried to keep track of the Kruzenshtern but news was hard to get. Her future was looking bleak and there was a possibility she might never sail again. But a gift from the German Government of 11 million deutschmarks (about A$7 million) had her sailing again, still under a Russian flag.

Then in 1996 they heard the ship was to circumnavigate the globe to celebrate her 70th birthday. “We tried to get them to come to Melbourne; we wrote to Canberra; we worked really hard on the idea of hosting a visit,” says Liz ruefully. But the only planned port of call was Fremantle and the ship wasn’t taking on any foreigners. So they jumped on a plane to Perth, found that no-one seemed to know about the ship, persuaded the pilot to take them on his boat, and drawing alongside the ship, created their own personal welcoming party, waving madly all the while to Mamikon, the bosun.

Inveigling permission to crew on the next leg to Capetown, the two women combed the local op shops for work clothes, madly rang the local media to build some interest in the ship and were interviewed on radio.

The voyage across the Indian Ocean with big swells rolling up from the Atlantic was unforgettable. “The ship just powered along. It was so exhilarating. The feeling of speed, knowing it’s all happening just with the free and clean energy of the wind. You look up at the bridge and the officers are all there with big grins. Every single person is feeling it.”

They hit a Force 11 gale just before the Cape of Good Hope. They two of them were told later it is one of the most dangerous coasts in the world. You get holes in the sea. The water beneath you drops away just as a wave comes over the top. “We loved it,” says Liz. Tossed about in all this sky and sea and howling wind, they saw storm petrels, albatrosses... “It was just wonderful.”

Liz likes Joseph Conrad’s thoughts on this. He says sailing is like being on your own planet; on it is everything you need. You are a little self-contained world sailing across an amazing universe.

“It’s hard to become a normal person after experiencing that,” she says.