Kit Sleeman looks back to an age of real service when fresh milk and bread appeared on the kitchen table every morning as if by magic.

By Kit Sleeman

MY VERY earliest childhood memory involves an illness when I was about three. I had a very high fever, which caused hallucinations. Symptoms of this kind were not to be sneezed at, given the times. It was still the age of polio epidemics. Jonas Salk invented his polio vaccine the year I was born, but it was not until I was about six or seven that the threat of polio had receded. Kids with leg braces, who had survived polio, were not an uncommon sight. “You’ll get locked up in an iron lung”, was used as a threat for misdemeanours like not washing hands.

I don’t remember the treatment or unpleasantness of my illness, but even now, the memory of the hallucination is quite clear. It was my behaviour during the hallucination that convinced Mum and Dad to take me to the hospital in the middle of the night. They said that I appeared to be not of this world during the event.

I spent a few days in hospital and do not know what the illness was, but given the symptoms and duration, it was probably something like viral meningitis, which can be caused by a bug related to polio. I survived that illness, but for several years I periodically had a recurring nightmare. It commenced like a migraine attack with changing patterns of light. From there it progressed to a surreal sort of landscape with geometric shapes that became rooms where the walls were not of fixed dimensions and kept changing. Either I was trapped inside and was unable to find a way out, or there was a malignant presence, never fully seen, outside and trying to get in.

Whichever scenario played out, I would wake up screaming. Unsurprisingly, these dreams made me wary of bedtimes. I had to be convinced, before getting into bed, that there were no monsters under the bed or creatures lurking in wardrobes. Mum would assure me that nothing could get into the house because the doors were all closed, but I detected some holes in her argument: tooth-fairies seemed to have no trouble finding my bedroom, and Santa always made it to the Christmas tree.

In fact, Santa seemed to be so comfortable wandering around my house that he usually had time to scoff some food, drink a beer and write some poetry. If they could get in, then why could the bogeyman and his mates not? I was also puzzled by some food items that appeared daily during the night without apparent human intervention.

How did they appear if no-one came into the house at night? Each night Mum would put a large empty billycan on the kitchen table. Each morning when I got up, I would find that it had been magically filled with milk during the night. Not only that, but next to the billycan would be a loaf of fresh bread, sometimes so fresh that it was still warm and fragrant.

How did that happen without visitations? I made enquiries and got mumbled responses about milkmen and breadmen who came while it was still dark. Great. I’m supposed to feel safe and cosy in my bed because bogeymen can’t get into the house, but tooth-fairies, Santas, milkmen and breadmen wander in at will.

I decided to investigate further. As the days got warmer and lighter and we moved toward summer, I tried to wake up earlier and earlier. Dad usually got up first; because one of his jobs was to light the kitchen stove so Mum could cook breakfast when she got up a bit later. I joined Dad on the early watch. One day I got up very early and my puzzle was solved. Dad hadn’t even started to light the fire yet. Instead he was sitting at the table with a little old man with a wizened, sunburnt face and bald head, smoking cigarettes and talking quietly.

Dad introduced me to Welshie, the milkman: I now knew what a milkman looked like. Not only that, I found out where our milk came from – he had not yet made his delivery. When he finished his smoke, he positioned our billycan on the floor and filled it from a big milk can that he had with him, and then put it back on the table. Then off he went with his can to the horse and dray waiting for him at our back gate, loaded with similar cans.

MY VERY earliest childhood memory involves an illness when I was about three. I had a very high fever, which caused hallucinations. Symptoms of this kind were not to be sneezed at, given the times. It was still the age of polio epidemics. Jonas Salk invented his polio vaccine the year I was born, but it was not until I was about six or seven that the threat of polio had receded. Kids with leg braces, who had survived polio, were not an uncommon sight. “You’ll get locked up in an iron lung”, was used as a threat for misdemeanours like not washing hands.

I don’t remember the treatment or unpleasantness of my illness, but even now, the memory of the hallucination is quite clear. It was my behaviour during the hallucination that convinced Mum and Dad to take me to the hospital in the middle of the night. They said that I appeared to be not of this world during the event.

I spent a few days in hospital and do not know what the illness was, but given the symptoms and duration, it was probably something like viral meningitis, which can be caused by a bug related to polio. I survived that illness, but for several years I periodically had a recurring nightmare. It commenced like a migraine attack with changing patterns of light. From there it progressed to a surreal sort of landscape with geometric shapes that became rooms where the walls were not of fixed dimensions and kept changing. Either I was trapped inside and was unable to find a way out, or there was a malignant presence, never fully seen, outside and trying to get in.

Whichever scenario played out, I would wake up screaming. Unsurprisingly, these dreams made me wary of bedtimes. I had to be convinced, before getting into bed, that there were no monsters under the bed or creatures lurking in wardrobes. Mum would assure me that nothing could get into the house because the doors were all closed, but I detected some holes in her argument: tooth-fairies seemed to have no trouble finding my bedroom, and Santa always made it to the Christmas tree.

In fact, Santa seemed to be so comfortable wandering around my house that he usually had time to scoff some food, drink a beer and write some poetry. If they could get in, then why could the bogeyman and his mates not? I was also puzzled by some food items that appeared daily during the night without apparent human intervention.

How did they appear if no-one came into the house at night? Each night Mum would put a large empty billycan on the kitchen table. Each morning when I got up, I would find that it had been magically filled with milk during the night. Not only that, but next to the billycan would be a loaf of fresh bread, sometimes so fresh that it was still warm and fragrant.

How did that happen without visitations? I made enquiries and got mumbled responses about milkmen and breadmen who came while it was still dark. Great. I’m supposed to feel safe and cosy in my bed because bogeymen can’t get into the house, but tooth-fairies, Santas, milkmen and breadmen wander in at will.

I decided to investigate further. As the days got warmer and lighter and we moved toward summer, I tried to wake up earlier and earlier. Dad usually got up first; because one of his jobs was to light the kitchen stove so Mum could cook breakfast when she got up a bit later. I joined Dad on the early watch. One day I got up very early and my puzzle was solved. Dad hadn’t even started to light the fire yet. Instead he was sitting at the table with a little old man with a wizened, sunburnt face and bald head, smoking cigarettes and talking quietly.

Dad introduced me to Welshie, the milkman: I now knew what a milkman looked like. Not only that, I found out where our milk came from – he had not yet made his delivery. When he finished his smoke, he positioned our billycan on the floor and filled it from a big milk can that he had with him, and then put it back on the table. Then off he went with his can to the horse and dray waiting for him at our back gate, loaded with similar cans.

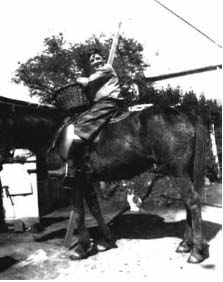

Meat delivery, Wonthaggi

Meat delivery, Wonthaggi A little while later, a second horse, with a covered van this time, pulled up and our bread was delivered by another man, the breadman, whose name I’ve forgotten. The mystery of the magic food appearance and night-time visitors was solved.

There was another night-time visitor, but he only came once a week and only as far as the back fence. We did our best to keep out of his way and there was very little mystery about him, because he could be smelled well before he came into sight. He was the ‘Dunny-man’, the man who removed full lavatory pans and replaced them with empty ones.

There were also some regular day visitors. When I was small, we did not have a fridge, but an ice-box which needed regular resupply with ice. Along would come another horse and dray, this time loaded with big rectangular blocks of ice, which seemed to be almost as big as me. The iceman would grab one of these with a special pair of large tongs, sling it over his shoulder which was protected by a hessian bag, bring it to the ice chest and reload it.

Our groceries were also delivered by horse and dray. This time the visitor was the driver, Dabba Taffe. If I happened to be walking along the street when Dabba went past, he would stop and pick me up. I’d then ride on the dray amongst all of the groceries. I used to like that very much. Dabba did not even have to direct the horse – he would just slowly plod along until Dabba stopped him to make a delivery.

There never used to be any locked house doors, so it’s just as well that the bogeyman did not call. Doors were left open so delivery people could get in. Their money would be waiting for them on the kitchen table, with a note if there were any changes of order to be made.

Last, but certainly not least, was the coal man. One of the benefits of being a State Coal Mine employee was a regular coal delivery. Mister Spunner would roll up every month or so in a battered green tip truck, back into the back yard and drop off a couple of tons of coal which we used for heating, cooking and hot water generation.

It may have been mainly horses and carts, but it was a better level of service than today.

There was another night-time visitor, but he only came once a week and only as far as the back fence. We did our best to keep out of his way and there was very little mystery about him, because he could be smelled well before he came into sight. He was the ‘Dunny-man’, the man who removed full lavatory pans and replaced them with empty ones.

There were also some regular day visitors. When I was small, we did not have a fridge, but an ice-box which needed regular resupply with ice. Along would come another horse and dray, this time loaded with big rectangular blocks of ice, which seemed to be almost as big as me. The iceman would grab one of these with a special pair of large tongs, sling it over his shoulder which was protected by a hessian bag, bring it to the ice chest and reload it.

Our groceries were also delivered by horse and dray. This time the visitor was the driver, Dabba Taffe. If I happened to be walking along the street when Dabba went past, he would stop and pick me up. I’d then ride on the dray amongst all of the groceries. I used to like that very much. Dabba did not even have to direct the horse – he would just slowly plod along until Dabba stopped him to make a delivery.

There never used to be any locked house doors, so it’s just as well that the bogeyman did not call. Doors were left open so delivery people could get in. Their money would be waiting for them on the kitchen table, with a note if there were any changes of order to be made.

Last, but certainly not least, was the coal man. One of the benefits of being a State Coal Mine employee was a regular coal delivery. Mister Spunner would roll up every month or so in a battered green tip truck, back into the back yard and drop off a couple of tons of coal which we used for heating, cooking and hot water generation.

It may have been mainly horses and carts, but it was a better level of service than today.