As the Americans and Russians battled for supremacy in space, a young Kit Sleeman scanned the skies from Wonthaggi.

By Kit Sleeman

EVERY Saturday afternoon I used to go to the matinee at Wonthaggi’s Union Theatre. Usually, and especially in summertime, I would go early and walk beyond the theatre to Booth’s milk bar and buy an iceberg. An iceberg was a paper cup heaped with shaved ice and topped with whatever coloured sweet flavouring you fancied. Eating it lasted till about half-way through the matinee.

Each week’s matinee session had the same composition: a Movietone newsreel with the pair of laughing kookaburras at the start, a cartoon or two and an exciting instalment of a serial (hence you had to go each week to keep up with the story line, not that it was too sophisticated). At the end, they played the national anthem of the time (God Save the Queen) over “inspiring” footage of a young queen doing her stuff. You were expected to stand at attention for that rubbish, but I can’t really recall many kids doing so: there was a sprint for the doors.

Rolling jaffas and generally yahooing was normal behaviour from the childish audience, unless a particularly good film was on. This misbehaviour had the potential to get you thrown out mid-session or might even result in physical damage. The darkened theatre was prowled by the Good Behaviour Enforcer, Tuillio Moresco. Tuillio’s presence struck momentary terror into all the kids when he was near.

He was a miner and ex-boxer, a big bloke with a gruff voice. He carried a huge torch and if he caught anyone misbehaving, he would belt them over the head with it and then drag them out of the theatre by the collar. Baiting him and getting away with it was a sport for the brave-hearted.

We did not particularly realise it, but the serials were quite old: cops and robbers style G-men or the Cisco Kid, Lone Ranger and even Tom Mix cowboy serials were made in the 1930s and 1940s. Then one Saturday, one started that captured a subject that was appearing more and more in the news: Space. As it happened, Buck Rogers was also old – it was filmed in 1939, but it was new film territory for us. Not long after, a cartoon appeared about the same subject: Daffy Duck as Duck Dodgers in the 24½th Century (it was newer, made in 1953, but still old).

Space started to capture childhood attention and imagination. Sheb Wooley’s song The Purple People Eater, about an unidentified flying object, was always on the radio. We had many philosophical arguments about what it meant: was it a purple creature that ate people, or was it a creature that ate purple people?

Films showing for adults were all about alien invasions from space. Space monsters were everywhere. I even got to meet one: Robby the Robot, from the movie The Forbidden Planet (1956), did a publicity tour of Australia. On one of our periodic day trips to Melbourne for clothes shopping, Robby was performing at Myers, and I got to see him in operation and right up close. He was very BIG and scary and impressive to my four- or five-year-old self.

It got worse. We did not have a TV at the time, but on Sunday nights, I’d go to Webby’s place next door and watch Disneyland. I liked the cartoons and each Sunday hoped the night’s show would be from Fantasyland and that maybe Donald Duck would be on. But week after week, the program was from “Tomorrowland”. I got thoroughly sick of Werhner von Braun’s German accent as he rabbited on about space travel, but I did come out the other end believing that the mighty USA was so far ahead in the ‘Space Race’ that there was no second place getter.

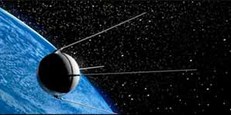

So October 4th 1957 was SHOCK and HORROR. The sneaky Russians had beaten America into space with the launch of Sputnik 1. There were full-page headlines in the newspapers (you can probably imagine those in the Sun, the morning tabloid, and the Herald, the afternoon broadsheet, as they were then) and the radio had updates all day.

This was miraculous stuff: Earth had a satellite other than the moon for the first time. We and the neighbours spent the night in the back yard scanning the skies, and eventually we did see it on its first night orbiting Earth. It is hard to describe just how exciting it all seemed to be.

Sputnik lasted for three months in orbit and fell to Earth the day after my sixth birthday.

In the meantime Lassie and Rin Tin Tin had been displaced as doggie heroes. Just a month after Sputnik’s launch a dog named Laika became the first critter in space to orbit the Earth. Her name became a household word and was so popular that the Russians had to invent a story to cover up the real nature of her demise. They said she was painlessly euthanised by remote control before her oxygen ran out. In actual fact there was a cooling control problem and she was cooked after a few orbits.

The space race was really on and the Ruskies were flogging the Yanks. Schoolyard conversation was all about the latest developments. But nothing prepared us for 1961.

Suddenly from nowhere in April, the Reds had a man in space: Yuri Gagarin was orbiting the Earth. Everyone was dumbfounded: the newspapers had been telling us that America was in front and about to launch a manned rocket (which they did in May with Alan Shepard, but that was non-orbital, just up and down), so they lied again.

After that, people lost interest. They wrote off the Americans as the Russians in following years did more and more dramatic trips into space. The interest did not really return until the Apollo moon-shots.

But apart from spending June 20 1969 glued to a TV at school, watching grainy images either from the moon or from Stanley Kubrick’s purpose-built secret film-lot (if you believe the conspiracy theorists), I was no longer really interested: it was not as exciting as Sputnik.

EVERY Saturday afternoon I used to go to the matinee at Wonthaggi’s Union Theatre. Usually, and especially in summertime, I would go early and walk beyond the theatre to Booth’s milk bar and buy an iceberg. An iceberg was a paper cup heaped with shaved ice and topped with whatever coloured sweet flavouring you fancied. Eating it lasted till about half-way through the matinee.

Each week’s matinee session had the same composition: a Movietone newsreel with the pair of laughing kookaburras at the start, a cartoon or two and an exciting instalment of a serial (hence you had to go each week to keep up with the story line, not that it was too sophisticated). At the end, they played the national anthem of the time (God Save the Queen) over “inspiring” footage of a young queen doing her stuff. You were expected to stand at attention for that rubbish, but I can’t really recall many kids doing so: there was a sprint for the doors.

Rolling jaffas and generally yahooing was normal behaviour from the childish audience, unless a particularly good film was on. This misbehaviour had the potential to get you thrown out mid-session or might even result in physical damage. The darkened theatre was prowled by the Good Behaviour Enforcer, Tuillio Moresco. Tuillio’s presence struck momentary terror into all the kids when he was near.

He was a miner and ex-boxer, a big bloke with a gruff voice. He carried a huge torch and if he caught anyone misbehaving, he would belt them over the head with it and then drag them out of the theatre by the collar. Baiting him and getting away with it was a sport for the brave-hearted.

We did not particularly realise it, but the serials were quite old: cops and robbers style G-men or the Cisco Kid, Lone Ranger and even Tom Mix cowboy serials were made in the 1930s and 1940s. Then one Saturday, one started that captured a subject that was appearing more and more in the news: Space. As it happened, Buck Rogers was also old – it was filmed in 1939, but it was new film territory for us. Not long after, a cartoon appeared about the same subject: Daffy Duck as Duck Dodgers in the 24½th Century (it was newer, made in 1953, but still old).

Space started to capture childhood attention and imagination. Sheb Wooley’s song The Purple People Eater, about an unidentified flying object, was always on the radio. We had many philosophical arguments about what it meant: was it a purple creature that ate people, or was it a creature that ate purple people?

Films showing for adults were all about alien invasions from space. Space monsters were everywhere. I even got to meet one: Robby the Robot, from the movie The Forbidden Planet (1956), did a publicity tour of Australia. On one of our periodic day trips to Melbourne for clothes shopping, Robby was performing at Myers, and I got to see him in operation and right up close. He was very BIG and scary and impressive to my four- or five-year-old self.

It got worse. We did not have a TV at the time, but on Sunday nights, I’d go to Webby’s place next door and watch Disneyland. I liked the cartoons and each Sunday hoped the night’s show would be from Fantasyland and that maybe Donald Duck would be on. But week after week, the program was from “Tomorrowland”. I got thoroughly sick of Werhner von Braun’s German accent as he rabbited on about space travel, but I did come out the other end believing that the mighty USA was so far ahead in the ‘Space Race’ that there was no second place getter.

So October 4th 1957 was SHOCK and HORROR. The sneaky Russians had beaten America into space with the launch of Sputnik 1. There were full-page headlines in the newspapers (you can probably imagine those in the Sun, the morning tabloid, and the Herald, the afternoon broadsheet, as they were then) and the radio had updates all day.

This was miraculous stuff: Earth had a satellite other than the moon for the first time. We and the neighbours spent the night in the back yard scanning the skies, and eventually we did see it on its first night orbiting Earth. It is hard to describe just how exciting it all seemed to be.

Sputnik lasted for three months in orbit and fell to Earth the day after my sixth birthday.

In the meantime Lassie and Rin Tin Tin had been displaced as doggie heroes. Just a month after Sputnik’s launch a dog named Laika became the first critter in space to orbit the Earth. Her name became a household word and was so popular that the Russians had to invent a story to cover up the real nature of her demise. They said she was painlessly euthanised by remote control before her oxygen ran out. In actual fact there was a cooling control problem and she was cooked after a few orbits.

The space race was really on and the Ruskies were flogging the Yanks. Schoolyard conversation was all about the latest developments. But nothing prepared us for 1961.

Suddenly from nowhere in April, the Reds had a man in space: Yuri Gagarin was orbiting the Earth. Everyone was dumbfounded: the newspapers had been telling us that America was in front and about to launch a manned rocket (which they did in May with Alan Shepard, but that was non-orbital, just up and down), so they lied again.

After that, people lost interest. They wrote off the Americans as the Russians in following years did more and more dramatic trips into space. The interest did not really return until the Apollo moon-shots.

But apart from spending June 20 1969 glued to a TV at school, watching grainy images either from the moon or from Stanley Kubrick’s purpose-built secret film-lot (if you believe the conspiracy theorists), I was no longer really interested: it was not as exciting as Sputnik.