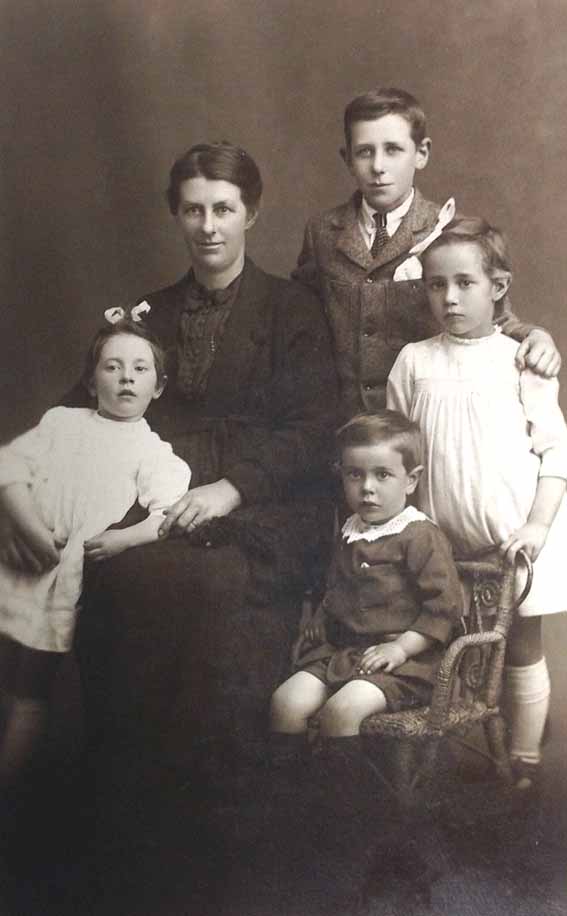

Emily Alice Sanne, 1939

Emily Alice Sanne, 1939 By Kit Sleeman

THE Sannes were a pioneering family of Kilcunda. Sanne is a name Swedish in origin and my Great Aunt Millie, born in the 1880s, was the last Australian family member to remain in contact with the Swedish ancestral family.

THE Sannes were a pioneering family of Kilcunda. Sanne is a name Swedish in origin and my Great Aunt Millie, born in the 1880s, was the last Australian family member to remain in contact with the Swedish ancestral family.

The matriarch of the family at Kilcunda was my great grandmother, Emily Alice (I don’t know her maiden name) who was born near Devonport, Tasmania, in March 1862. Together with her family, she moved to Kilcunda, then in its pioneering days, in about 1873.

At that time, there was a coal mine operated by Watson and Latham and a train/tram line for transporting coal was laid between Kilcunda and the ship-loading station at Griffiths Point/San Remo. This was a narrow-gauge line, originally with horse-drawn carts, but may have been converted to steam-drawn at a later date. Wonthaggi was known in those days simply as “The Wild Cattle Run”.

Emily married my great grandfather, Martin Sanne, in about 1881. Martin was then working as a drill foreman at the mine. He had also worked as a fisherman and in 1901 was instrumental in the salvage of the Artisan, which was shipwrecked on a rock shelf near Harmers Haven during a storm. Martin allegedly built a house at Kilcunda from timber salvaged from the Artisan: this may be the house mentioned in Great Aunt Emily’s poem.

According to a family legend, Martin was also the first person to swim from San Remo to Philip Island. This feat was carried out under some duress: he was being chased by some angry market gardeners waving farm tools after being caught red handed stealing from their fields. Depending on who told the story, Martin was allegedly chased from either Corinella or Kilcunda to San Remo before his enforced swim. This may well be a tall story, but it was perpetuated by his daughters, my grand aunts, and told to me when I was young.

Emily senior lived at Kilcunda for 46 years before moving on. She died aged 83 at Camberwell in 1945. Emily and Martin raised 10 children while at Kilcunda and her newspaper death notice implies that all 10 were alive at the time of her death. Such a survival rate of children is quite remarkable for the time.

The children born at Kilcunda were Millie, Charlie, Florrie (my grandmother), Edie, Fred, Lizzie, Frank, George, Emily and Raymond.

My grandmother, Florrie Sleeman, was well known to me because she lived mainly in Wonthaggi where she raised my father, Beau, and his siblings Paddy, Hazel and Merle.

At that time, there was a coal mine operated by Watson and Latham and a train/tram line for transporting coal was laid between Kilcunda and the ship-loading station at Griffiths Point/San Remo. This was a narrow-gauge line, originally with horse-drawn carts, but may have been converted to steam-drawn at a later date. Wonthaggi was known in those days simply as “The Wild Cattle Run”.

Emily married my great grandfather, Martin Sanne, in about 1881. Martin was then working as a drill foreman at the mine. He had also worked as a fisherman and in 1901 was instrumental in the salvage of the Artisan, which was shipwrecked on a rock shelf near Harmers Haven during a storm. Martin allegedly built a house at Kilcunda from timber salvaged from the Artisan: this may be the house mentioned in Great Aunt Emily’s poem.

According to a family legend, Martin was also the first person to swim from San Remo to Philip Island. This feat was carried out under some duress: he was being chased by some angry market gardeners waving farm tools after being caught red handed stealing from their fields. Depending on who told the story, Martin was allegedly chased from either Corinella or Kilcunda to San Remo before his enforced swim. This may well be a tall story, but it was perpetuated by his daughters, my grand aunts, and told to me when I was young.

Emily senior lived at Kilcunda for 46 years before moving on. She died aged 83 at Camberwell in 1945. Emily and Martin raised 10 children while at Kilcunda and her newspaper death notice implies that all 10 were alive at the time of her death. Such a survival rate of children is quite remarkable for the time.

The children born at Kilcunda were Millie, Charlie, Florrie (my grandmother), Edie, Fred, Lizzie, Frank, George, Emily and Raymond.

My grandmother, Florrie Sleeman, was well known to me because she lived mainly in Wonthaggi where she raised my father, Beau, and his siblings Paddy, Hazel and Merle.

Florence and Millie in about 1950

Florence and Millie in about 1950 My grandmother’s sisters Millie and Emily were regular occasional visitors to Wonthaggi until well advanced in age. They were both full of historical tales about Kilcunda as it was in their youth. At every visit they demanded a drive tour around Kilcunda and the hills of its hinterland to renew their memories and love of the place.

As a kid, I used to very much enjoy their historical monologues as we drove about: they described an entirely different perspective from what I viewed through the car window.

Raymond was also a fairly regular visitor and is buried at Kilcunda cemetery, but the others I saw only rarely or never. I think Fred visited once.

Frank visited a couple of times, and the first time scared the willies out of me. I met him unexpectedly in our backyard one day when I was about four years old. He had been badly disfigured in either a sawmill accident or during military service, and was missing a few fingers and had a badly scarred face. I found it very confronting at the time.

Frank had joined the navy at about 17 and, after completing four years’ service at sea, enlisted in the World War 1 army. He served in the 29th Infantry Battalion fighting on the Western Front at some very nasty places like Polygon Wood, Fromelles, St Quentin Canal, Amiens and Bullecourt.

Great Aunt Emily’s poem is a reflection of a simple girlhood life lived at Kilcunda in the late 19th and early 20th century. I’m not sure when it was written, but other documents with it suggest maybe in the 1940s, 20 or so years after she left Kilcunda.

She clearly loved Kilcunda and that love and the memories remained with her all her life.

As a kid, I used to very much enjoy their historical monologues as we drove about: they described an entirely different perspective from what I viewed through the car window.

Raymond was also a fairly regular visitor and is buried at Kilcunda cemetery, but the others I saw only rarely or never. I think Fred visited once.

Frank visited a couple of times, and the first time scared the willies out of me. I met him unexpectedly in our backyard one day when I was about four years old. He had been badly disfigured in either a sawmill accident or during military service, and was missing a few fingers and had a badly scarred face. I found it very confronting at the time.

Frank had joined the navy at about 17 and, after completing four years’ service at sea, enlisted in the World War 1 army. He served in the 29th Infantry Battalion fighting on the Western Front at some very nasty places like Polygon Wood, Fromelles, St Quentin Canal, Amiens and Bullecourt.

Great Aunt Emily’s poem is a reflection of a simple girlhood life lived at Kilcunda in the late 19th and early 20th century. I’m not sure when it was written, but other documents with it suggest maybe in the 1940s, 20 or so years after she left Kilcunda.

She clearly loved Kilcunda and that love and the memories remained with her all her life.