By Liane Arno

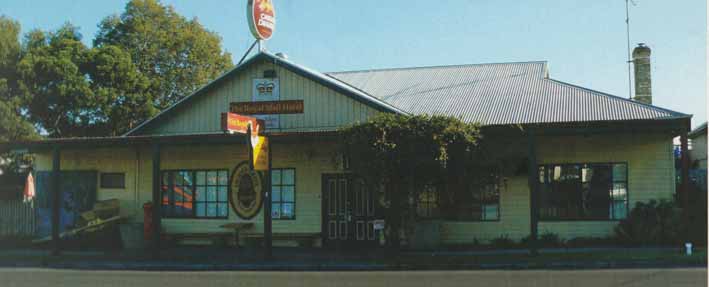

When we bought the Royal Mail hotel in Archies Creek, we didn’t know it only had a turnover (not profit – turnover) of $8000 in a year. My mother proclaimed it an abomination. A fire had burnt out part of the kitchen. When you walked through the kitchen, you literally walked through the white ant-eaten floorboards. A challenge, to say the least.

When we bought the Royal Mail hotel in Archies Creek, we didn’t know it only had a turnover (not profit – turnover) of $8000 in a year. My mother proclaimed it an abomination. A fire had burnt out part of the kitchen. When you walked through the kitchen, you literally walked through the white ant-eaten floorboards. A challenge, to say the least.

Matt Stone and Liane Arno

Matt Stone and Liane Arno Like many sea changers, we had no idea what we were getting ourselves in to. We had decided we would find a business – any business – so long as it was within half an hour of where my parents lived in Korumburra South.

The Archie Creek locals accepted us in the way they do, politely informing us that we had not really bought the hotel, we had just borrowed it from them for a while. Like many places in the country nobody operates by their real name. You only have to look at Matt to see that he resembles Basil Fawlty and so the name of Baz was born. They tried to call me Sybil, but I resisted and so we ended up agreeing on Mrs Fawlty. The names stuck.

Our first customer was Norman – or at least he almost was. Matt turned up for the settlement of the pub on a rainy day in December. Maurice, the previous owner, was there in faded hard yakka stubbies trying desperately to contain a straining beer belly and a four-day growth. The pub was a mess. Maurice was a hoarder and every room was filled to the rafters with a collection of rubbish and rat droppings that had accumulated in the 10 years that he owned it.

The pub had sunk into the mud and Matt was greeted with a flood coming in through the back door ruining the carpets that Maurice was quick to point out had only yesterday been steam cleaned.

In conducting the inventory, Matt came across the cool room blowing hot air. “What’s going on here, Maurice?” Cool rooms are of course fairly necessary in providing cold beer to customers.

“I had it inspected the other day and they said it was running just fine.”

“What as? An oven?!?”

It was so overwhelming that Matt got into his car, turned back to Melbourne and rang me to cancel the settlement. As luck would have it the settlement had already occurred, and the truck full of all of our stuff – not to mention the gang of helpers – were on their way. I arrived a couple of hours later to find the “stock” of two warm slabs getting warmer in the “cool room” and a harassed Matt.

Needless to say, the thought of opening that night was an impossible dream, and so we decided to head off to the nearest pub. And that’s when we saw Norman heading down the hill to the pub that wasn’t going to open that night.

Norman was a lovable rogue who would drink his VB long necks throughout the day. He would regularly pop down to get his three or four long necks, tuck them under his arm, and head back up the hill to drink them in peace under the shade of the palm tree in his back yard. I asked him once, when I saw the long necks precariously balanced, if he had ever broken one. He said, “I broke my wrist watch once, and my shoulder another time, but I’ve never spilt a drop.”

He was a keen lover of the football but there sometimes wasn’t enough left over to put in for the footy tipping competition. So “Normie’s Gnome” was started. Matt would collect an extra 10 cents from each long neck to put in the gnome moneybox to save for the tipping. Believe me, he was never short.

Wonthaggi owes its existence to Norm’s great-grandfather, Richard Stephen Davis, who discovered coal here in 1841 prior to the creation of the state of Victoria. Leaving the Welsh mines and 14-hour days behind him, he sought a better life in Australia.

Richard boasted that he could tell if there was coal underground by the lay of the land. He found it on the shores of Harmers Haven near Wonthaggi. With his boots tied around his neck and his feet bare but covered with rags so that he would have decent boots to see Lieutenant Governor La Trobe, he carried a 25-pound bag of coal on his back in order to seek the offered £1000 reward (worth about $200,000 today) for finding a commercial quantity of coal. After receiving a warm response from La Trobe, he walked back to Kilcunda carrying two 50-pound bags of flour. Unable to carry 100 pounds (45 kilograms) of flour in one go, he walked 100 yards with one bag, then went back to retrieve the second – for over 100 miles!!

Despite the warm response, there were many complications. Only nine years later was he finally paid £400 – hardly worth his efforts. He was clearly dogged and persistent. Despite being illiterate, and only signing a mark on any contract he entered into, he made a huge difference to what was then a barren stretch of coast.

Norm’s wife, Amy also has a long history in the district. Her grandfather was on the committee of the Wonthaggi Workers Club – and most of her family were mine workers – everywhere from Kalgoorlie to Wonthaggi. She worked at the Archies Creek Butter Factory, along with Norman, at the time when the factory was one of the most innovative, winning prizes as far away as London, and selling to places as far flung as the Middle East. They worked there until it closed in 1983, and as Amy had, in her words, carried through one of her smartest ideas in buying one of the factory’s houses, were able to see out their retirement here in Archies Creek.

Amy works hard at keeping a beautiful garden whose centrepiece was a 60-year old palm tree. When St Kilda Road was being upgraded, a search began for all the old palm trees that had been planted around Victoria. Norm and Amy were offered over $15,000 for it. Despite the fact that the money would have been very handy, they refused to sell. You would understand why if you saw the garden.

Norm lost his fight to cancer a couple of years ago but Amy remains a strong figure in the community. She continues to volunteer at a number of local bodies. She also pops down for the odd glass of beer with a dash of soda at the weekend – just for old time’s sake. She never looks down the passage in the pub without remembering her days doing the cleaning at the pub for Jean Bethune, down on her hands and knees and scrubbing that wretched dark red inlaid lino in the days before modern floor polishers and light-weight vacuum cleaners. In those days she would be paid £2 a day. Wouldn’t even pay for her glass of beer these days.

This is an edited extract from Liane Arno’s book A Matter of Complete Embuggerance, a collection of portraits of the regulars at the Royal Mail Hotel.

The Archie Creek locals accepted us in the way they do, politely informing us that we had not really bought the hotel, we had just borrowed it from them for a while. Like many places in the country nobody operates by their real name. You only have to look at Matt to see that he resembles Basil Fawlty and so the name of Baz was born. They tried to call me Sybil, but I resisted and so we ended up agreeing on Mrs Fawlty. The names stuck.

Our first customer was Norman – or at least he almost was. Matt turned up for the settlement of the pub on a rainy day in December. Maurice, the previous owner, was there in faded hard yakka stubbies trying desperately to contain a straining beer belly and a four-day growth. The pub was a mess. Maurice was a hoarder and every room was filled to the rafters with a collection of rubbish and rat droppings that had accumulated in the 10 years that he owned it.

The pub had sunk into the mud and Matt was greeted with a flood coming in through the back door ruining the carpets that Maurice was quick to point out had only yesterday been steam cleaned.

In conducting the inventory, Matt came across the cool room blowing hot air. “What’s going on here, Maurice?” Cool rooms are of course fairly necessary in providing cold beer to customers.

“I had it inspected the other day and they said it was running just fine.”

“What as? An oven?!?”

It was so overwhelming that Matt got into his car, turned back to Melbourne and rang me to cancel the settlement. As luck would have it the settlement had already occurred, and the truck full of all of our stuff – not to mention the gang of helpers – were on their way. I arrived a couple of hours later to find the “stock” of two warm slabs getting warmer in the “cool room” and a harassed Matt.

Needless to say, the thought of opening that night was an impossible dream, and so we decided to head off to the nearest pub. And that’s when we saw Norman heading down the hill to the pub that wasn’t going to open that night.

Norman was a lovable rogue who would drink his VB long necks throughout the day. He would regularly pop down to get his three or four long necks, tuck them under his arm, and head back up the hill to drink them in peace under the shade of the palm tree in his back yard. I asked him once, when I saw the long necks precariously balanced, if he had ever broken one. He said, “I broke my wrist watch once, and my shoulder another time, but I’ve never spilt a drop.”

He was a keen lover of the football but there sometimes wasn’t enough left over to put in for the footy tipping competition. So “Normie’s Gnome” was started. Matt would collect an extra 10 cents from each long neck to put in the gnome moneybox to save for the tipping. Believe me, he was never short.

Wonthaggi owes its existence to Norm’s great-grandfather, Richard Stephen Davis, who discovered coal here in 1841 prior to the creation of the state of Victoria. Leaving the Welsh mines and 14-hour days behind him, he sought a better life in Australia.

Richard boasted that he could tell if there was coal underground by the lay of the land. He found it on the shores of Harmers Haven near Wonthaggi. With his boots tied around his neck and his feet bare but covered with rags so that he would have decent boots to see Lieutenant Governor La Trobe, he carried a 25-pound bag of coal on his back in order to seek the offered £1000 reward (worth about $200,000 today) for finding a commercial quantity of coal. After receiving a warm response from La Trobe, he walked back to Kilcunda carrying two 50-pound bags of flour. Unable to carry 100 pounds (45 kilograms) of flour in one go, he walked 100 yards with one bag, then went back to retrieve the second – for over 100 miles!!

Despite the warm response, there were many complications. Only nine years later was he finally paid £400 – hardly worth his efforts. He was clearly dogged and persistent. Despite being illiterate, and only signing a mark on any contract he entered into, he made a huge difference to what was then a barren stretch of coast.

Norm’s wife, Amy also has a long history in the district. Her grandfather was on the committee of the Wonthaggi Workers Club – and most of her family were mine workers – everywhere from Kalgoorlie to Wonthaggi. She worked at the Archies Creek Butter Factory, along with Norman, at the time when the factory was one of the most innovative, winning prizes as far away as London, and selling to places as far flung as the Middle East. They worked there until it closed in 1983, and as Amy had, in her words, carried through one of her smartest ideas in buying one of the factory’s houses, were able to see out their retirement here in Archies Creek.

Amy works hard at keeping a beautiful garden whose centrepiece was a 60-year old palm tree. When St Kilda Road was being upgraded, a search began for all the old palm trees that had been planted around Victoria. Norm and Amy were offered over $15,000 for it. Despite the fact that the money would have been very handy, they refused to sell. You would understand why if you saw the garden.

Norm lost his fight to cancer a couple of years ago but Amy remains a strong figure in the community. She continues to volunteer at a number of local bodies. She also pops down for the odd glass of beer with a dash of soda at the weekend – just for old time’s sake. She never looks down the passage in the pub without remembering her days doing the cleaning at the pub for Jean Bethune, down on her hands and knees and scrubbing that wretched dark red inlaid lino in the days before modern floor polishers and light-weight vacuum cleaners. In those days she would be paid £2 a day. Wouldn’t even pay for her glass of beer these days.

This is an edited extract from Liane Arno’s book A Matter of Complete Embuggerance, a collection of portraits of the regulars at the Royal Mail Hotel.