Meg Viney’s creative journey starts with cast-offs.

By Liane Arno

STOP reading right now. Look outside your window and look at nature’s cast-offs. Look at the eucalyptus leaves that have dropped from your native gum trees now stressed with the heat. Look at the pine needles that have made a silent carpet under the canopy. Now take your eyes to the leaves you have peeled off the cauliflower head before cooking your dinner and the rhubarb leaves that lie discarded in the organic waste bin. I want you to look at them with fresh eyes. I want you to look at them with the eyes of Meg Viney.

For Meg, these cast-offs are the start of a journey of creating the most exquisite forms.

She is constantly searching for inspiration from nature. Nothing escapes her attention as she contemplates how any fibrous material can be re-shaped and used for one of her wondrous, ethereal creations.

Meg was born at a time when career choices were limited and education for women unusual. The term fibre artist did not exist. Working with fibres at that time meant knitting or weaving functional pieces – scarves and jumpers.

It was only in the 1970s that fibre art came into its own, spearheaded by women such as Meg who had a traditional understanding of the use of fibre in the domestic sphere. For the first time, works could be figurative or fanciful, prioritising aesthetic value over utility. Meg’s work was immediately in demand, and is now found in collections around the world, including Dame Elisabeth Murdoch’s. It has delighted and confounded a multitude. Each of her pieces has a story behind it, some confronting social issues, others simply expressing joy. Many of her works are figurative, but in her eyes, they are vessels, containers of life, of love, of one another.

Before meeting Meg Viney, I did my research and found a constant reference to “containment’” being central to her work. Her description was of it being a safe place out of which to emerge -- the assurance of emotional, spiritual and physical security. And yet when I looked at the dictionary definition of “containment” my Google search provided, “the action of keeping something harmful under control or within limits”.

When I met this vivacious, energetic woman, who seems constantly on the move, I found it hard to reconcile the dictionary definition with what I saw. As I learned more about her, I realised that in the 1970s when Meg started creating her art in California – where her new husband had compelled her to travel and settle – it was her way of escaping from the controlling, shallow, materialistic, narcissistic world she found herself in.

She would escape into “a zone” – of comfort and safety, totally immersed in creation. Some of her work is almost disturbing as there is no place for the figures to speak, no mouths for words to form, silent witnesses to a foreign land, and then with others there are many mouths – mouths with which to heal, to succour.

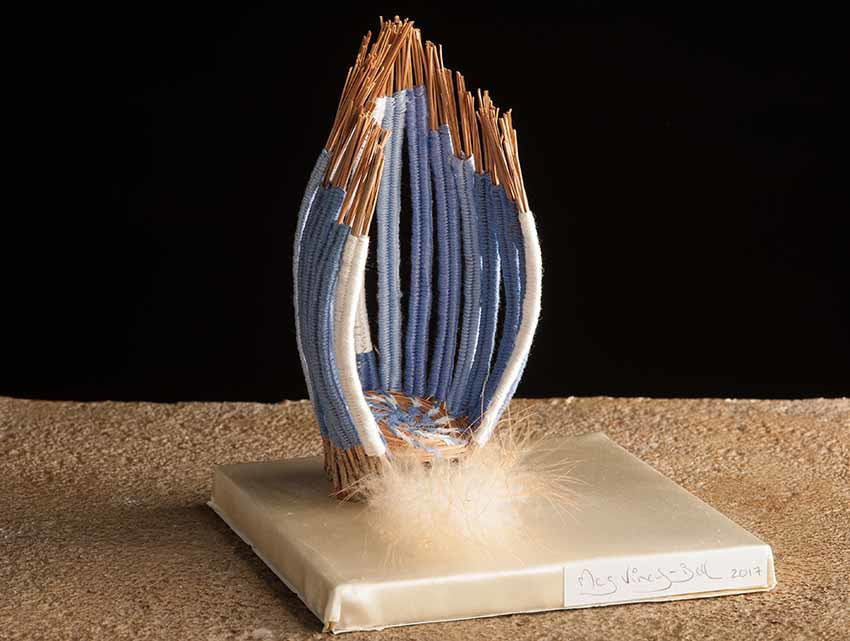

Her latest exhibition, Sipapu, now at Wonthaggi’s ArtSpace, derives its existence from her love of tribal cultures, in this case, in particular, the Hopi people of Arizona.

The name Hopi is a shortened form of Hopituh Shi-nu-mu, which means Peaceful People. The Hopi’s belief system involves a state of total reverence and respect for all things, and living in accordance with the instructions of Maasaw, the Creator or Caretaker of Earth. The Hopi observe their traditional ceremonies for the benefit of the entire world.

The Hopi Indians believe their ancient ancestors were underground dwellers living in kivas, and were “born” when a shrike (bird with sharp beak) pecked a hole in the earth's surface. They changed from their lizard-like state and were able to emerge as the First Peoples of the Earth. Sipapu is the Hopi word for this small hole in the floor of a kiva.

While the Hopi created above-ground dwellings, the shaman (spiritual leader) remained in the kiva in which a fire was constantly tended. A tribesperson wishing to see the shaman would descend though this hole into the smoke-filled kiva. The descent through this Sipapu symbolized the transition from the secular to the sacred world. Emergence symbolised a new life.

For Meg, living in the heart of California in the 1980s, the Sipapu became another symbol for containment and she has continued with this theme up to the present day.

It is not only the Hopi people who have influenced Meg but also the Japanese culture. Through this culture Meg believes that it is her role as an artist to bring the essence of all materials into existence. “It is like a midwife ensuring the safe emergence of a child,” she says.

Shibori is the Japanese art of dyeing with a traditional indigo bath with the earliest known example dating from the 8th century.

There are an infinite number of ways an artist can bind, stitch, fold, twist, or compress material for Shibori. Each way results in very different patterns which are multiplied by the type of material used. “Accidental changes” are welcomed by Meg as she seeks a perfect combination for the materials she uses.

Today Meg finds sanctuary in Koonwarra with her beloved Bill and her cavoodle, which is almost as animated as she is. She has one big project in front of her, she says. “I think that might be my last.” I look across at her and we both know she is kidding herself.

Meg Viney’s exhibition 'Sipapu' runs at ArtSpace Gallery until February 19. You can find more of her work at www.megviney.com.

STOP reading right now. Look outside your window and look at nature’s cast-offs. Look at the eucalyptus leaves that have dropped from your native gum trees now stressed with the heat. Look at the pine needles that have made a silent carpet under the canopy. Now take your eyes to the leaves you have peeled off the cauliflower head before cooking your dinner and the rhubarb leaves that lie discarded in the organic waste bin. I want you to look at them with fresh eyes. I want you to look at them with the eyes of Meg Viney.

For Meg, these cast-offs are the start of a journey of creating the most exquisite forms.

She is constantly searching for inspiration from nature. Nothing escapes her attention as she contemplates how any fibrous material can be re-shaped and used for one of her wondrous, ethereal creations.

Meg was born at a time when career choices were limited and education for women unusual. The term fibre artist did not exist. Working with fibres at that time meant knitting or weaving functional pieces – scarves and jumpers.

It was only in the 1970s that fibre art came into its own, spearheaded by women such as Meg who had a traditional understanding of the use of fibre in the domestic sphere. For the first time, works could be figurative or fanciful, prioritising aesthetic value over utility. Meg’s work was immediately in demand, and is now found in collections around the world, including Dame Elisabeth Murdoch’s. It has delighted and confounded a multitude. Each of her pieces has a story behind it, some confronting social issues, others simply expressing joy. Many of her works are figurative, but in her eyes, they are vessels, containers of life, of love, of one another.

Before meeting Meg Viney, I did my research and found a constant reference to “containment’” being central to her work. Her description was of it being a safe place out of which to emerge -- the assurance of emotional, spiritual and physical security. And yet when I looked at the dictionary definition of “containment” my Google search provided, “the action of keeping something harmful under control or within limits”.

When I met this vivacious, energetic woman, who seems constantly on the move, I found it hard to reconcile the dictionary definition with what I saw. As I learned more about her, I realised that in the 1970s when Meg started creating her art in California – where her new husband had compelled her to travel and settle – it was her way of escaping from the controlling, shallow, materialistic, narcissistic world she found herself in.

She would escape into “a zone” – of comfort and safety, totally immersed in creation. Some of her work is almost disturbing as there is no place for the figures to speak, no mouths for words to form, silent witnesses to a foreign land, and then with others there are many mouths – mouths with which to heal, to succour.

Her latest exhibition, Sipapu, now at Wonthaggi’s ArtSpace, derives its existence from her love of tribal cultures, in this case, in particular, the Hopi people of Arizona.

The name Hopi is a shortened form of Hopituh Shi-nu-mu, which means Peaceful People. The Hopi’s belief system involves a state of total reverence and respect for all things, and living in accordance with the instructions of Maasaw, the Creator or Caretaker of Earth. The Hopi observe their traditional ceremonies for the benefit of the entire world.

The Hopi Indians believe their ancient ancestors were underground dwellers living in kivas, and were “born” when a shrike (bird with sharp beak) pecked a hole in the earth's surface. They changed from their lizard-like state and were able to emerge as the First Peoples of the Earth. Sipapu is the Hopi word for this small hole in the floor of a kiva.

While the Hopi created above-ground dwellings, the shaman (spiritual leader) remained in the kiva in which a fire was constantly tended. A tribesperson wishing to see the shaman would descend though this hole into the smoke-filled kiva. The descent through this Sipapu symbolized the transition from the secular to the sacred world. Emergence symbolised a new life.

For Meg, living in the heart of California in the 1980s, the Sipapu became another symbol for containment and she has continued with this theme up to the present day.

It is not only the Hopi people who have influenced Meg but also the Japanese culture. Through this culture Meg believes that it is her role as an artist to bring the essence of all materials into existence. “It is like a midwife ensuring the safe emergence of a child,” she says.

Shibori is the Japanese art of dyeing with a traditional indigo bath with the earliest known example dating from the 8th century.

There are an infinite number of ways an artist can bind, stitch, fold, twist, or compress material for Shibori. Each way results in very different patterns which are multiplied by the type of material used. “Accidental changes” are welcomed by Meg as she seeks a perfect combination for the materials she uses.

Today Meg finds sanctuary in Koonwarra with her beloved Bill and her cavoodle, which is almost as animated as she is. She has one big project in front of her, she says. “I think that might be my last.” I look across at her and we both know she is kidding herself.

Meg Viney’s exhibition 'Sipapu' runs at ArtSpace Gallery until February 19. You can find more of her work at www.megviney.com.