Where most of see chaos, Werner Theinert sees patterns.

By Liane Arno

HAVE you ever taken a picnic out to one of our beautiful nature spots in the Bass Coast and, after you’ve had your fill of food and wine and conversation, lain on your back in the grass or on the sand and looked up at the sky?

Have you watched the clouds mass and swirl above you, creating intricate patterns – perhaps seen mythical creatures form in the twists of smoky entrails? Werner Theinert has. What’s more, he played with those images, rolling them over and over in his mind, calling on his imagination to create something more meaningful from a puff of smoke.

Werner takes high quality digital photographs with so many megapixels that only the most modern of computers can successfully process the final 1.5GB images. The photographs are of his world around him – of his work – and where he lives. And so they are the dichotomy of the swirling smoke stacks of the Latrobe Valley and the beauty that is the Bass Coast Shire. He then takes these images, duplicates them and manipulates these multiple images to create another much larger image that on the one hand is a complex and intriguing picture in itself – but then draws you in to explore every image that it contains.

HAVE you ever taken a picnic out to one of our beautiful nature spots in the Bass Coast and, after you’ve had your fill of food and wine and conversation, lain on your back in the grass or on the sand and looked up at the sky?

Have you watched the clouds mass and swirl above you, creating intricate patterns – perhaps seen mythical creatures form in the twists of smoky entrails? Werner Theinert has. What’s more, he played with those images, rolling them over and over in his mind, calling on his imagination to create something more meaningful from a puff of smoke.

Werner takes high quality digital photographs with so many megapixels that only the most modern of computers can successfully process the final 1.5GB images. The photographs are of his world around him – of his work – and where he lives. And so they are the dichotomy of the swirling smoke stacks of the Latrobe Valley and the beauty that is the Bass Coast Shire. He then takes these images, duplicates them and manipulates these multiple images to create another much larger image that on the one hand is a complex and intriguing picture in itself – but then draws you in to explore every image that it contains.

It might be difficult to imagine Werner as an artist. Not only is he an engineer (one of those left brain types, if you know what I mean) but he was also born in Germany. If ever there was a gene pool that determined a man to be quality driven, exact, uncompromising in his work and traditional, then Werner was born into it. And yet he has always had a desire to be creative.

He saw this desire realised when in Bahrain, working as an expat at an aluminium smelters power plant, he experienced a severe rainstorm that shook the drought-ridden country. Huge African blackwood trees were the victims. These mighty trees provided a lifetime supply of beautiful timber for Werner’s creativity. He paints an evocative image as he describes watching the timber he collected, like “chocolate slowly drying”. He went to a local Indian engineering shop whose owner was only too happy for Werner to work with him in his workplace to create the machinery he needed to turn the wood. He knew from the start that he could realise his dream of being creative and it wasn’t long before his colleagues were buying pieces from him.

When Werner returned to Australia after the start of the Second Gulf War, he had to go back to work here to make ends meet. He went back to the Latrobe Valley and made sure he found a house to live in that had a huge shed – half filled with clay for his wife, Ursula’s love of pottery, and half filled with wood for his love of turning. Ursula had enrolled in art classes and he became really envious of her heading off to the local TAFE to master her skills whilst he had to go to work. It wasn’t long before he asked his boss if he could work four days a week, and then three, so he could join his wife in her classes. Studying under Chris Myers at Yallourn TAFE, Werner delighted in making a flat piece of clay into large three-dimensional pieces of art.

What started off as a need to photograph his ceramics became an obsession. Already an eBay nut, Werner bought more and more sophisticated equipment to ensure the best results. Sadly all he has to show of his ceramics now are photographs as when the Black Saturday bushfires raged through their home the ceramics didn’t take kindly to be fired a second time. They turned to chalk.

Werner gives credit to Peter Biram, a photography and visual arts teacher at Yallourn TAFE. Starting in a darkroom with chemicals, Werner couldn’t create the intricate patterns he wanted, and so Peter gave him permission to take his creativity where he wanted to. That meant going digital.

The ultimate resolution that Werner was seeking was 720 dots per square inch. This was initially made possible by an extremely high resolution negative scanner. With such high resolution Werner was able to create amazing images but then faced the challenge of how to print them. A couple of hundred dollars to print and the same again to frame a 700mm x 700mm print of, frankly, poor quality at a photographic studio was not appealing. He tried many alternatives without success until he discovered that sign writers are also artists and they have the ability to print high resolution images on material that will last for many years in all kinds of weather.

Werner was looking not just for a “technician” but an artist, and found one in Rob Mortimer. In many ways, Rob was a man like Werner, obsessive about quality, so much so that he made many 1 inch test strips at a time to check the vibrancy of the image. As Werner walked along the finished product, he realised Rob had enabled him to take his art to the next level.

Werner is still experimenting. Not only in printing the images, but in their creation. He started with spiral masses that sprang from watching the clouds roll by, and then gave them a twist as though spiralling down into the abyss. Then onto the geometric with no concession to anything other than sharp and angular shapes.

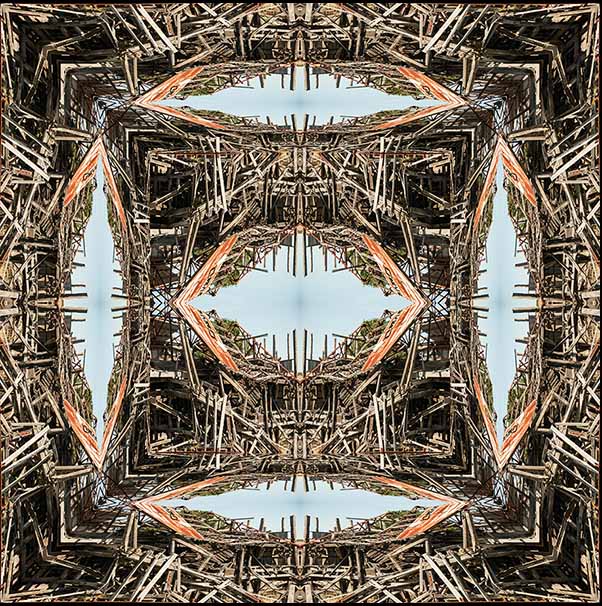

Brace 5 Square, digital print by Werner Theinert

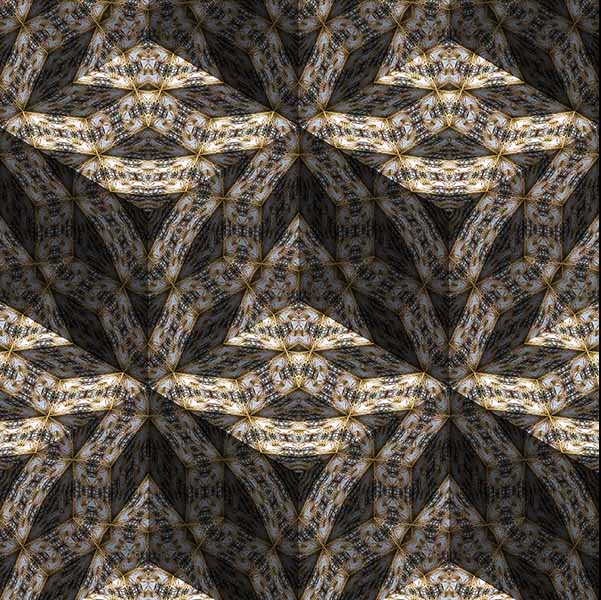

Brace 5 Escher, digital print by Werner Theinert

And now – who knows? He takes between 200 to 400 photos in a single session because he knows that from these there will be at least a handful of gems that he can take and further manipulate. His latest idea is to capture wind turbines at night with the aid of a long exposure and a powerful torch to capture their movement against the night sky. Or perhaps it will be a long pier stretching out into the moonlight with the silver sheen reflecting the sky that captures his imagination.

Whatever he comes up with next I can’t wait to see it.

Werner Theinert's studio/gallery, Theinert Gallery,

3 Chisholm Road, Wonthaggi, is open from 6-8pm next Saturday, May 13 as part of the Creative Gippsland Festival.

He saw this desire realised when in Bahrain, working as an expat at an aluminium smelters power plant, he experienced a severe rainstorm that shook the drought-ridden country. Huge African blackwood trees were the victims. These mighty trees provided a lifetime supply of beautiful timber for Werner’s creativity. He paints an evocative image as he describes watching the timber he collected, like “chocolate slowly drying”. He went to a local Indian engineering shop whose owner was only too happy for Werner to work with him in his workplace to create the machinery he needed to turn the wood. He knew from the start that he could realise his dream of being creative and it wasn’t long before his colleagues were buying pieces from him.

When Werner returned to Australia after the start of the Second Gulf War, he had to go back to work here to make ends meet. He went back to the Latrobe Valley and made sure he found a house to live in that had a huge shed – half filled with clay for his wife, Ursula’s love of pottery, and half filled with wood for his love of turning. Ursula had enrolled in art classes and he became really envious of her heading off to the local TAFE to master her skills whilst he had to go to work. It wasn’t long before he asked his boss if he could work four days a week, and then three, so he could join his wife in her classes. Studying under Chris Myers at Yallourn TAFE, Werner delighted in making a flat piece of clay into large three-dimensional pieces of art.

What started off as a need to photograph his ceramics became an obsession. Already an eBay nut, Werner bought more and more sophisticated equipment to ensure the best results. Sadly all he has to show of his ceramics now are photographs as when the Black Saturday bushfires raged through their home the ceramics didn’t take kindly to be fired a second time. They turned to chalk.

Werner gives credit to Peter Biram, a photography and visual arts teacher at Yallourn TAFE. Starting in a darkroom with chemicals, Werner couldn’t create the intricate patterns he wanted, and so Peter gave him permission to take his creativity where he wanted to. That meant going digital.

The ultimate resolution that Werner was seeking was 720 dots per square inch. This was initially made possible by an extremely high resolution negative scanner. With such high resolution Werner was able to create amazing images but then faced the challenge of how to print them. A couple of hundred dollars to print and the same again to frame a 700mm x 700mm print of, frankly, poor quality at a photographic studio was not appealing. He tried many alternatives without success until he discovered that sign writers are also artists and they have the ability to print high resolution images on material that will last for many years in all kinds of weather.

Werner was looking not just for a “technician” but an artist, and found one in Rob Mortimer. In many ways, Rob was a man like Werner, obsessive about quality, so much so that he made many 1 inch test strips at a time to check the vibrancy of the image. As Werner walked along the finished product, he realised Rob had enabled him to take his art to the next level.

Werner is still experimenting. Not only in printing the images, but in their creation. He started with spiral masses that sprang from watching the clouds roll by, and then gave them a twist as though spiralling down into the abyss. Then onto the geometric with no concession to anything other than sharp and angular shapes.

Brace 5 Square, digital print by Werner Theinert

Brace 5 Escher, digital print by Werner Theinert

And now – who knows? He takes between 200 to 400 photos in a single session because he knows that from these there will be at least a handful of gems that he can take and further manipulate. His latest idea is to capture wind turbines at night with the aid of a long exposure and a powerful torch to capture their movement against the night sky. Or perhaps it will be a long pier stretching out into the moonlight with the silver sheen reflecting the sky that captures his imagination.

Whatever he comes up with next I can’t wait to see it.

Werner Theinert's studio/gallery, Theinert Gallery,

3 Chisholm Road, Wonthaggi, is open from 6-8pm next Saturday, May 13 as part of the Creative Gippsland Festival.