For over 150 years, Phillip Island has been a natural haven for weary city folk, writes Linda Cuttriss, but there are dark clouds on the horizon.

Cartoon Natasha Williams-Novak

Cartoon Natasha Williams-Novak By Linda Cuttriss

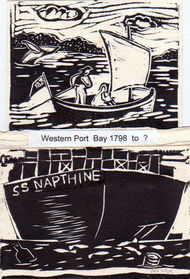

GEORGE Bass was certainly an intrepid explorer, but the name he gave to Western Port in January 1798 has a few things about it that don’t quite fit. I suppose he wasn’t to know that Western Port would end up east of the Port of Melbourne, Australia’s largest port. Besides that, there was no port there, no place to unload ships. It was home to the Boonwurrung people who had lived there for thousands of years. But perhaps his most obvious error was to omit to call it a bay.

Bass and his six-man crew left Sydney Cove in a 28-foot open whale boat to explore the south-east coast of the continent. He arrived through the narrow Eastern Passage near present-day San Remo, looked around for 12 days and drew a rough map. Maybe he had run out of food, maybe he was ready for home or maybe he was eager to report this excellent place for ships to shelter from a storm. He left via the Western Passage without venturing around the corner to “discover” Port Phillip Bay.

Bass was as far west as anyone had yet reported in the Colony of New South Wales, so he named the place Western Port for its position relative to “every other known harbour on the coast”. No-one will ever know why he chose the word “port” instead of “harbour”, but if he had investigated further he would have known this place was a bay.

Almost 40 years after Bass rowed away, John Batman set up camp near the mouth of the Yarra. Other entrepreneurial pastoralists soon selected land around Western Port. In 1836 Samuel Anderson took up land near the Bass River. In 1842 the McHaffie brothers leased the whole of Phillip Island and in 1845 Mrs Martha Jane King established her run where Hastings now stands.

From the early years of European settlement, Phillip Island was a holiday retreat for Melbourne’s social elite. Baron von Mueller, Governor George Bowen and Superintendent Hare (of Ned Kelly fame) were among those who travelled by buggy then boat across Western Port to visit the McHaffies.

Although Melbourne was a fraction of its current size in the 1860s, newspapers were reporting opportunities for its citizens to get out of town for a spot of shooting, boating or just relaxing. An article in The Australian News for Home Readers on February 23, 1866 extolled the virtues of the fishing village of Hastings and picturesque French Island in Western Port as an “ideal retreat …. free from the bustle of city life”.

From the 1870s, gentlemen and ladies stayed at the Isle of Wight in Cowes, promenaded along the jetty and went boating on Green Lake. In the early 1900s, a nine-hole golf course and guest house were established on the Summerland Peninsula near the site of the now world-famous Penguin Parade. Celebrated garden designer Edna Walling was one of those who visited.

Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton were two of many renowned artists to capture Phillip Island’s scenic beauty. Eugene von Guerard first visited the island in 1869. Charles Blackman painted Night Tide at Flinders in 1957 after walking in the moonlight near the sea with friends. In 1955 Australian landscape painter Arthur Boyd painted Lovers in a Boat, Hastings. Fred Williams depicted two scenes of the tidal flats at Cannons Creek in 1974.

By the 1920s, when Bert West took the first tours to see penguins by torchlight, Phillip Island had long been a place to come for a nature experience. The island was marketed as the “natural attraction” well before the term “nature-based tourism” was coined.

Phillip Island has always had a sense of isolation despite its proximity to Melbourne. In the Sydney Morning Herald on September 20 1933, M. D. Sefton wrote of “Phillip Island: An Australian Variety Spot”. He was delighted by “the pretty coast of the mainland opposite, the calm clear waters and the sandy beaches”. He marvelled at the wildlife – the seals, penguins, muttonbirds and koalas – but the thing that most fascinated him was how people “wonder at their feats of going from Melbourne to a distant land in fifty miles of travel”.

Phillip Island’s popularity as a holiday destination picked up pace after a bridge connected it to the mainland in 1940. In the decades that followed, more and more Melbourne folk came for a day trip, for the weekend or for their holidays. They came to fish, swim and surf, view the wildlife, walk along the beach or simply laze around and read.

Generations of Melbournians have fond childhood memories of summer holidays at Somers, Flinders or Phillip Island. While mums and dads sheltered under beach umbrellas, the kids made sandcastles, rode body boards to the shore or investigated underwater rock-pool worlds. In the evenings they had family barbecues or fish and chips on the beach.

Although there are more houses now and more visitors come, the nature of Phillip Island, the Mornington Peninsula and Western Port remains relatively unchanged. The bay is still a playground for Melbourne’s ever-swelling population. Holiday makers still swim at Cowes beach just as they did when the old sea-baths were built in 1893.

Cowes Jetty (circa 1900). Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria

Cowes Jetty, January 2014. Photo: Linda Cuttriss

Now there are plans for Hastings, in the upper reaches of the bay, to become Australia’s biggest port. Currently Hastings handles about 60 ships a year; if the port expansion proceeds, that will increase 50-fold to around 3000 mega container ships.

No-one knows for sure what changes a major port will bring to this extraordinary, much-loved bay.

How will it feel to swim at Cowes with multiple ships parked nearby, waiting their turn to dock at Hastings?

How will it feel when the narrow Western Passage between Phillip Island and the mainland has become a megaship freeway?

And how will Melbourne holiday makers feel when their once-beautiful getaway has been transformed to just another industrial site?

GEORGE Bass was certainly an intrepid explorer, but the name he gave to Western Port in January 1798 has a few things about it that don’t quite fit. I suppose he wasn’t to know that Western Port would end up east of the Port of Melbourne, Australia’s largest port. Besides that, there was no port there, no place to unload ships. It was home to the Boonwurrung people who had lived there for thousands of years. But perhaps his most obvious error was to omit to call it a bay.

Bass and his six-man crew left Sydney Cove in a 28-foot open whale boat to explore the south-east coast of the continent. He arrived through the narrow Eastern Passage near present-day San Remo, looked around for 12 days and drew a rough map. Maybe he had run out of food, maybe he was ready for home or maybe he was eager to report this excellent place for ships to shelter from a storm. He left via the Western Passage without venturing around the corner to “discover” Port Phillip Bay.

Bass was as far west as anyone had yet reported in the Colony of New South Wales, so he named the place Western Port for its position relative to “every other known harbour on the coast”. No-one will ever know why he chose the word “port” instead of “harbour”, but if he had investigated further he would have known this place was a bay.

Almost 40 years after Bass rowed away, John Batman set up camp near the mouth of the Yarra. Other entrepreneurial pastoralists soon selected land around Western Port. In 1836 Samuel Anderson took up land near the Bass River. In 1842 the McHaffie brothers leased the whole of Phillip Island and in 1845 Mrs Martha Jane King established her run where Hastings now stands.

From the early years of European settlement, Phillip Island was a holiday retreat for Melbourne’s social elite. Baron von Mueller, Governor George Bowen and Superintendent Hare (of Ned Kelly fame) were among those who travelled by buggy then boat across Western Port to visit the McHaffies.

Although Melbourne was a fraction of its current size in the 1860s, newspapers were reporting opportunities for its citizens to get out of town for a spot of shooting, boating or just relaxing. An article in The Australian News for Home Readers on February 23, 1866 extolled the virtues of the fishing village of Hastings and picturesque French Island in Western Port as an “ideal retreat …. free from the bustle of city life”.

From the 1870s, gentlemen and ladies stayed at the Isle of Wight in Cowes, promenaded along the jetty and went boating on Green Lake. In the early 1900s, a nine-hole golf course and guest house were established on the Summerland Peninsula near the site of the now world-famous Penguin Parade. Celebrated garden designer Edna Walling was one of those who visited.

Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton were two of many renowned artists to capture Phillip Island’s scenic beauty. Eugene von Guerard first visited the island in 1869. Charles Blackman painted Night Tide at Flinders in 1957 after walking in the moonlight near the sea with friends. In 1955 Australian landscape painter Arthur Boyd painted Lovers in a Boat, Hastings. Fred Williams depicted two scenes of the tidal flats at Cannons Creek in 1974.

By the 1920s, when Bert West took the first tours to see penguins by torchlight, Phillip Island had long been a place to come for a nature experience. The island was marketed as the “natural attraction” well before the term “nature-based tourism” was coined.

Phillip Island has always had a sense of isolation despite its proximity to Melbourne. In the Sydney Morning Herald on September 20 1933, M. D. Sefton wrote of “Phillip Island: An Australian Variety Spot”. He was delighted by “the pretty coast of the mainland opposite, the calm clear waters and the sandy beaches”. He marvelled at the wildlife – the seals, penguins, muttonbirds and koalas – but the thing that most fascinated him was how people “wonder at their feats of going from Melbourne to a distant land in fifty miles of travel”.

Phillip Island’s popularity as a holiday destination picked up pace after a bridge connected it to the mainland in 1940. In the decades that followed, more and more Melbourne folk came for a day trip, for the weekend or for their holidays. They came to fish, swim and surf, view the wildlife, walk along the beach or simply laze around and read.

Generations of Melbournians have fond childhood memories of summer holidays at Somers, Flinders or Phillip Island. While mums and dads sheltered under beach umbrellas, the kids made sandcastles, rode body boards to the shore or investigated underwater rock-pool worlds. In the evenings they had family barbecues or fish and chips on the beach.

Although there are more houses now and more visitors come, the nature of Phillip Island, the Mornington Peninsula and Western Port remains relatively unchanged. The bay is still a playground for Melbourne’s ever-swelling population. Holiday makers still swim at Cowes beach just as they did when the old sea-baths were built in 1893.

Cowes Jetty (circa 1900). Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria

Cowes Jetty, January 2014. Photo: Linda Cuttriss

Now there are plans for Hastings, in the upper reaches of the bay, to become Australia’s biggest port. Currently Hastings handles about 60 ships a year; if the port expansion proceeds, that will increase 50-fold to around 3000 mega container ships.

No-one knows for sure what changes a major port will bring to this extraordinary, much-loved bay.

How will it feel to swim at Cowes with multiple ships parked nearby, waiting their turn to dock at Hastings?

How will it feel when the narrow Western Passage between Phillip Island and the mainland has become a megaship freeway?

And how will Melbourne holiday makers feel when their once-beautiful getaway has been transformed to just another industrial site?

COMMENTS

September 9, 2014

We simply cannot allow beautiful near pristine Westernport Bay to be destroyed by this ridiculous scheme. No one should have the right to do that.

Kate Pick, Cowes

Excellent Sept. issue. I loved the collaborative piece by Linda and Natasha. Keep up the good work!

Jill Shannon, Ventnor

September 9, 2014

We simply cannot allow beautiful near pristine Westernport Bay to be destroyed by this ridiculous scheme. No one should have the right to do that.

Kate Pick, Cowes

Excellent Sept. issue. I loved the collaborative piece by Linda and Natasha. Keep up the good work!

Jill Shannon, Ventnor