Photos: Linda Cuttriss

Photos: Linda Cuttriss By Linda Cuttriss

IT IS such a simple thing, but I get a certain pleasure every time I cross the bridge. I briefly glance towards Cape Woolamai, check for fishing boats at the jetty and wonder what birds will be feeding in the shallows.

Today I have crossed to San Remo to walk the beach from the jetty towards the open sea.

I make my way along the path below San Remo Fisherman’s Co-op and take the stairs down to the beach. Two fancy fishing boats speed noisily towards the bridge while a tourist jetboat roars out along the channel. Several smaller fishing boats remain motionless off the sand bar.

IT IS such a simple thing, but I get a certain pleasure every time I cross the bridge. I briefly glance towards Cape Woolamai, check for fishing boats at the jetty and wonder what birds will be feeding in the shallows.

Today I have crossed to San Remo to walk the beach from the jetty towards the open sea.

I make my way along the path below San Remo Fisherman’s Co-op and take the stairs down to the beach. Two fancy fishing boats speed noisily towards the bridge while a tourist jetboat roars out along the channel. Several smaller fishing boats remain motionless off the sand bar.

There is a loud splash and I turn around to see two teenage boys have jumped from the jetty.

Sounds soften around the bend where a boulder rampart protects the land from coastal erosion. The tide is low and water laps softly on the shore. A light northerly breeze whispers at my back.

A singing honeyeater trills from the coastal scrub. A pied oystercatcher calls clear and sharp as it zooms past. Pied cormorants and seagulls rest on a rocky outcrop.

Then, a subtle change shifts in the air. I stop and look around. Where moments before there was only sand, now tiny wavelets chase each other to the shore. The tide has turned.

Sounds soften around the bend where a boulder rampart protects the land from coastal erosion. The tide is low and water laps softly on the shore. A light northerly breeze whispers at my back.

A singing honeyeater trills from the coastal scrub. A pied oystercatcher calls clear and sharp as it zooms past. Pied cormorants and seagulls rest on a rocky outcrop.

Then, a subtle change shifts in the air. I stop and look around. Where moments before there was only sand, now tiny wavelets chase each other to the shore. The tide has turned.

Standing on this vast expanse of sand, and flanked by a deep blue-water channel flowing out to sea, it is easy to imagine an ancient river valley here.

In the last phase of cold climate, 80,000 to 20,000 years ago, the sea fell at least 100 metres below its present level. As the atmosphere cooled, glaciers, ice sheets and snow fields grew in polar regions locking up frozen water and depleting the oceans.

The sea drained out of Western Port and the coastline lay west of King Island and east of Flinders Island, forming a land bridge to Tasmania. Western Port was a lowland bordered by hill country and the Bass River carved a channel through this lowland to flow out at what is now the Eastern Entrance to Western Port.

In the last phase of cold climate, 80,000 to 20,000 years ago, the sea fell at least 100 metres below its present level. As the atmosphere cooled, glaciers, ice sheets and snow fields grew in polar regions locking up frozen water and depleting the oceans.

The sea drained out of Western Port and the coastline lay west of King Island and east of Flinders Island, forming a land bridge to Tasmania. Western Port was a lowland bordered by hill country and the Bass River carved a channel through this lowland to flow out at what is now the Eastern Entrance to Western Port.

| On this warm summer day, families have set up beach shelters to enjoy a day at the beach. Youngsters play with buckets and spades watched over by their mums and dads. Dogs stand guard at the water’s edge as children swim and snorkel in the shallows. Weathered basalt cliffs curve behind the beach and fallen boulders warn not to seek shade beneath them. A spring seeps from the base of these cliffs formed from 50 million-year-old volcanic rock. Springwater trickles over a platform of sandstones and mudstones created 120 million years ago when this area was a swampland where dinosaurs lived. Across the water is Cape Woolamai, where a band of her 380 million-year-old pink granite slopes gently into the sea. I return along the path above the boulder rampart, the coastal scrub providing shade from the midday sun. When I reach The Narrows, aptly named for the narrow gap between San Remo and Phillip Island, the tide is rushing in. It is bubbling, broiling, glimmering, almost menacing. Meanwhile, a steady stream of vehicles trundles across the bridge. |

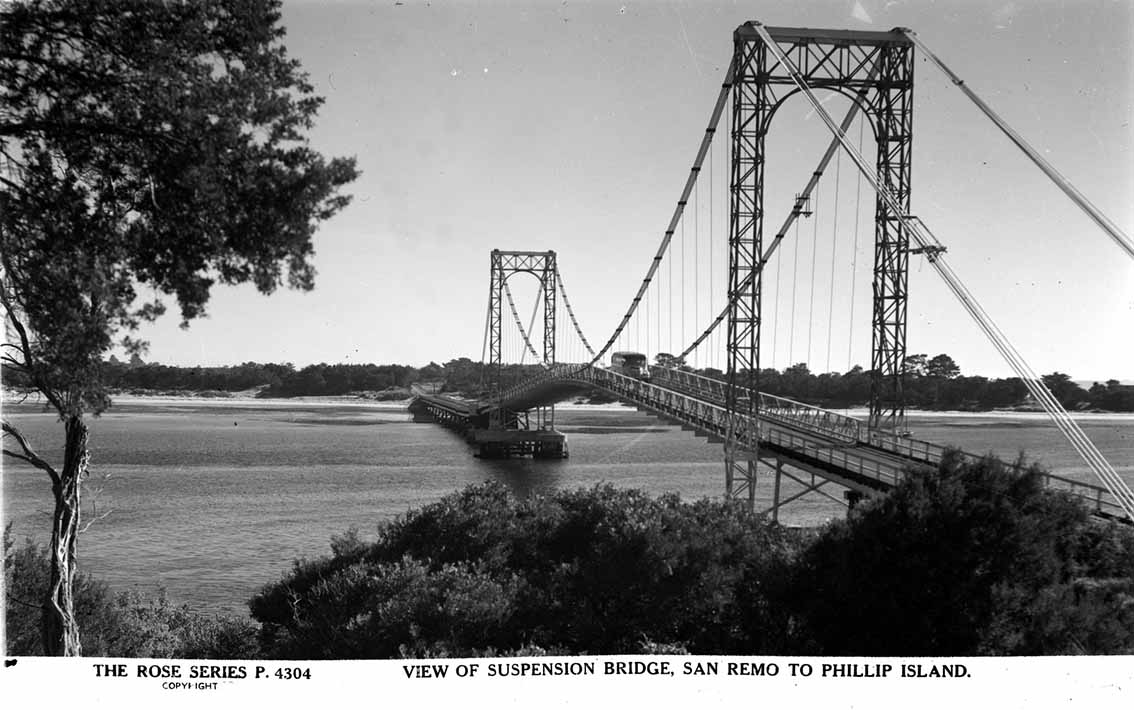

It wasn’t always so easy to cross The Narrows before a bridge was built. It is said that Yalluk-Bulluk people crossed in bark canoes and probably also swam. But they had few trappings to carry. It was more precarious for the early settlers who had to get cattle, horses, buggies, and later motor cars across the swiftly flowing channel.

In the early days, cattle were yarded on the beach, roped to a boat and towed to the opposite shore. But this was rarely a smooth affair as the cattle were usually wild and had never been handled before. When the gate was opened they invariably charged at the men and soon found themselves in deep water with no choice but to swim to the other side.

When a settler arrived by buggy it was driven onto the beach, unharnessed, hauled aboard the boat and often with wheels overhanging, transported across with the horse tied behind.

Later, vehicles drove onto a punt that was towed by a launch, but this was still a challenge. Often when the vessels reached the middle of the channel the wind and the tide would swing them broadside. Approaching the other side, the launch would speed up then swing out of the way and with luck the punt would land without mishap.

Eventually, after years of meetings and appeals to government led by Richard Grayden, an impressive suspension bridge was opened on November 29, 1940. It was replaced by the current bridge in 1969.

In the early days, cattle were yarded on the beach, roped to a boat and towed to the opposite shore. But this was rarely a smooth affair as the cattle were usually wild and had never been handled before. When the gate was opened they invariably charged at the men and soon found themselves in deep water with no choice but to swim to the other side.

When a settler arrived by buggy it was driven onto the beach, unharnessed, hauled aboard the boat and often with wheels overhanging, transported across with the horse tied behind.

Later, vehicles drove onto a punt that was towed by a launch, but this was still a challenge. Often when the vessels reached the middle of the channel the wind and the tide would swing them broadside. Approaching the other side, the launch would speed up then swing out of the way and with luck the punt would land without mishap.

Eventually, after years of meetings and appeals to government led by Richard Grayden, an impressive suspension bridge was opened on November 29, 1940. It was replaced by the current bridge in 1969.

Getting across The Narrows was once an arduous and risky necessity but now in February each year, hundreds of people of all ages and abilities willingly sign up for the San Remo Channel Challenge and pay to swim across.

Perhaps the biggest challenge of the day is deciding exactly when to sound the starting siren. Graeme Burgan, who for over 30 years has made the call, spends hours analysing the conditions in the lead-up to the day. Tide charts are just a prediction of tide times and there’s a lot going on in The Narrows he says. Conditions can change from one day to the next and every year is different.

The race is timed to start just before ‘slack water’, the brief period of calm water before the tide turns, when the tide is not running in and not running out. On a day when the tide is not very low, the period of slack water can last 15 or 20 minutes, but when there is a very low tide the water rushes quickly and there might only be five minutes of calm water.

It was a perfect scenario for this year’s event on February 10. With a record turnout of over 700 competitors, fifteen minutes of slack water gave time for four waves of swimmers, starting one and two minutes apart, to get safely across before the tide turned.

The 550-metre channel swim and two-kilometre run across the bridge to the finish line is a big event on the Bass Coast calendar, drawing competitors and spectators from near and far. One lane of the bridge is closed to vehicles for the duration of the event but as soon as it is over, the traffic resumes its steady flow across The Narrows.

Perhaps the biggest challenge of the day is deciding exactly when to sound the starting siren. Graeme Burgan, who for over 30 years has made the call, spends hours analysing the conditions in the lead-up to the day. Tide charts are just a prediction of tide times and there’s a lot going on in The Narrows he says. Conditions can change from one day to the next and every year is different.

The race is timed to start just before ‘slack water’, the brief period of calm water before the tide turns, when the tide is not running in and not running out. On a day when the tide is not very low, the period of slack water can last 15 or 20 minutes, but when there is a very low tide the water rushes quickly and there might only be five minutes of calm water.

It was a perfect scenario for this year’s event on February 10. With a record turnout of over 700 competitors, fifteen minutes of slack water gave time for four waves of swimmers, starting one and two minutes apart, to get safely across before the tide turned.

The 550-metre channel swim and two-kilometre run across the bridge to the finish line is a big event on the Bass Coast calendar, drawing competitors and spectators from near and far. One lane of the bridge is closed to vehicles for the duration of the event but as soon as it is over, the traffic resumes its steady flow across The Narrows.