| By Linda Cuttriss ON THE south coast of Phillip Island there is a lovely long beach rich with stories spanning millennia. Like elsewhere along Bass Coast, the beach at Forrest Caves was formed around six thousand years ago as a rising sea carried sand from the floor of Bass Strait to the raw edge of the land. Wind winnowed sand from these beaches building dunes that became covered with grasses and hardy shrubs. Parts of the land fringe became submerged as rocky reefs and those that remained close to the surface created habitats for abalone, limpets and other shellfish. Aboriginal family groups lived across the coastal lowlands that once connected the mainland to the island now known as Tasmania, before the sea flooded Bass Strait. It is hard to grasp the magnitude of change that generations of First People faced as the sea swallowed their lands and they were forced to retreat to higher ground. |

The Bunurong people, the First People of Bass Coast, were witness to this great change. Their stories are not mine to tell, but it is known that one of their seasonal campsites on this island of Millowl was a short distance inland from Forrest Caves. Remains of shellfish, wallaby, marsupial mouse, bush rat, penguin and shearwater have been found in middens here and quartz implements and other stone tools have also been uncovered. What an excellent place to spend the spring and summer months tucked behind the dunes, possibly in the shade of old moonah trees and sheltered from storms. Shellfish were accessible and abundant on the craggy basalt shore platforms, shearwaters were plentiful and pigface and coast beard heath berries were ripe for eating.

Colonialism crept across Bunurong Country in a more devastating way than the sea ever did. Traditional Bunurong life was brutally eroded away as sealers, pastoralists and wattle-bark woodcutters moved onto their lands and family groups that for generations had spent the warmer months on Millowl no longer came.

Colonialism crept across Bunurong Country in a more devastating way than the sea ever did. Traditional Bunurong life was brutally eroded away as sealers, pastoralists and wattle-bark woodcutters moved onto their lands and family groups that for generations had spent the warmer months on Millowl no longer came.

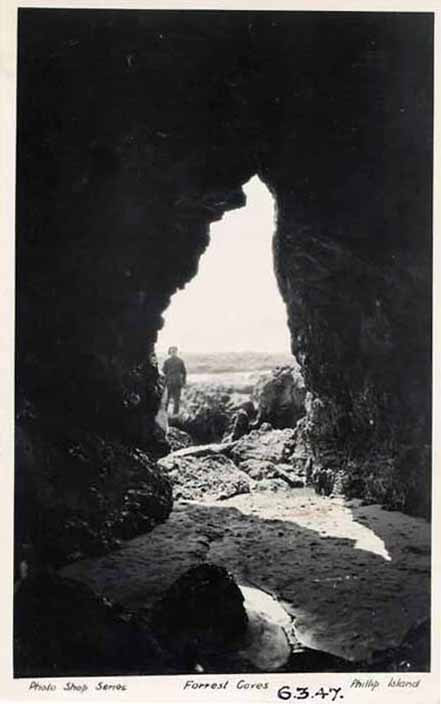

| Some decades later, after Phillip Island was opened for closer settlement in 1868, the Forrest family established a homestead and farm near Forrest Caves. Before long grazing by cattle, sheep and rabbits had destroyed the protective dune vegetation. Sand mobilised by the wind drifted inland, steadily creeping, looming larger, spilling towards the family home. The farmhouse was moved but the cowshed, stables and pigsties were eventually buried beneath a great pile of sand. European marram grass was planted to stabilise the sand and restore the dunes along the island’s fringe. It is said that marram grass builds steeper dunes than would naturally occur along this coast and this would appear to be true from the commanding views at the top of the stairs at Forrest Caves car park. Bass Strait stretches to the southern horizon between Cape Woolamai and Pyramid Rock and the waters of Western Port can be seen glimmering to the north. Marram grass still dominates the high dunes but clumps of silvery velvet leaves spreading across the lower slopes show native hairy spinifex grass is now taking hold. At the eastern end of the beach a sprawling mass of red tuff, rock formed from compacted volcanic ash, has been hollowed out by the sea to form Forrest Caves, one of many natural features attracting tourists to this island since the early 1900s. A 1940s postcard taken from inside Forrest Caves looking out to sea shows a man standing outside on the rocks. The man is dwarfed by the cave entrance and the roof reaches high above. The roof has now mostly collapsed into a jumble of boulders and the entrance is barely a metre above my head but the caves still hold a fascination and people venture within to explore what might be hiding there. Sunlight streams into the grotto and there are echoes of water trickling out with the tide. The rock is wrinkled and pocked and the sea has carved ledges and cavities where limpets, chitons and thick clusters of purple barnacles grow. Gardens of bright-green marine algae flourish among small tidal pools perched on the crusty rock. Beyond the caves towards Forrest Bluff is a cornucopia of delights for rock lovers. Volcanic basalt cliffs are weathered into crumbling clay and cliffs of tuff into patterned walls of red, brown, white and pink topped with cascading succulent plants. Great multi-coloured piles of cobbles and pebbles are strewn about the base of the cliffs, worn smooth from tumbling around when the tide is in. Beds of sea grapes (Neptune’s necklace) adorn the dissected shore platform exposed by low tide. Encrustations of tiny tube worms decorate the edges of intertidal rockpools carved into pink tuff. Some rocks are baked to shiny purple and seem to be melting in the sun. When the tide is right and the wind blows from the land, swell that has travelled from deep in the Southern Ocean rears up as it reaches the shallows forming waves that surfers come here to ride. The offshore breeze holds up and smooths the face of the wave while its energy drives it along, its fluttering crest hovering, then peeling and spilling over until it crashes onto the shore in a massive explosion of white water. Here at the edge of the wide blue sea the shoreline moves ceaselessly with the tide, its shape ever changing as the swash of each wave leaves arcs of tiny bubbles on the sand. While the rocks give a sense of permanence they are slowly breaking up and wearing down. No wave is the same. The sun shifts through the sky. Storms roll in and move away. As I stop to watch a Pacific Gull ride upon the wind, it is quite thrilling to know this moment will never happen again. |