The author's mother Irene went underground for the first time in 2014 to see the conditions in which her father had worked for 43 years.

The author's mother Irene went underground for the first time in 2014 to see the conditions in which her father had worked for 43 years. IN 1925 my grandfather Jack Thompson emigrated from a coal mining town in the north of England to work in the State Coal Mine, Wonthaggi, where he worked until the mine closed in 1968. My grandmother Emily followed with their young son a year later, after Jack had found a house for them.

My mum Irene grew up in Reed Crescent and became a secretary at the Wonthaggi Co-operative Society Store where she worked until she married. Grandma bought medications from the Miners’ Dispensary, Grandad had a beer with mates at the Workmen’s Club on Saturdays, and on weekends Irene and her friends went to the pictures at the Union Theatre (now Wonthaggi Union Community Arts Centre).

Like other descendants of Wonthaggi’s coal miners, the State Coal Mine is in my DNA. I was born in Wonthaggi Hospital, my first summer holiday job at 14 was in the haberdashery section of the co-op store (now the IGA) and I went to the pictures at the Union Theatre with friends. Although I grew up near Inverloch we visited Grandma and Grandad in Wonthaggi every week and I often stayed overnight. I smelt the coal fires burning, I watched Grandma make Grandad’s crib and I knew only too well that Grandad worked underground in the mine.

Mum had asked her father many times when she was a girl to take her underground but it didn’t ever happen. She said he almost did but, “I was about fifteen. Dad was all set and we were excited. Finally, he was going to take us after school, Roma Hassen and I. Then Father changed his mind. He hated the idea of us seeing where he worked”.

One sunny day in February 2014 we arrived at the State Coal Mine Heritage Area for the underground tour. Mum and I were excited and my dad Len was just as keen. After lunch at the café we strolled around the miner’s cottage and Mum reminisced about the familiar furniture, the copper wash tub in the laundry and the ‘outhouse’ at the back of the garden. She laughed and said, “I remember having to walk out at night, it was such a long way down the yard”.

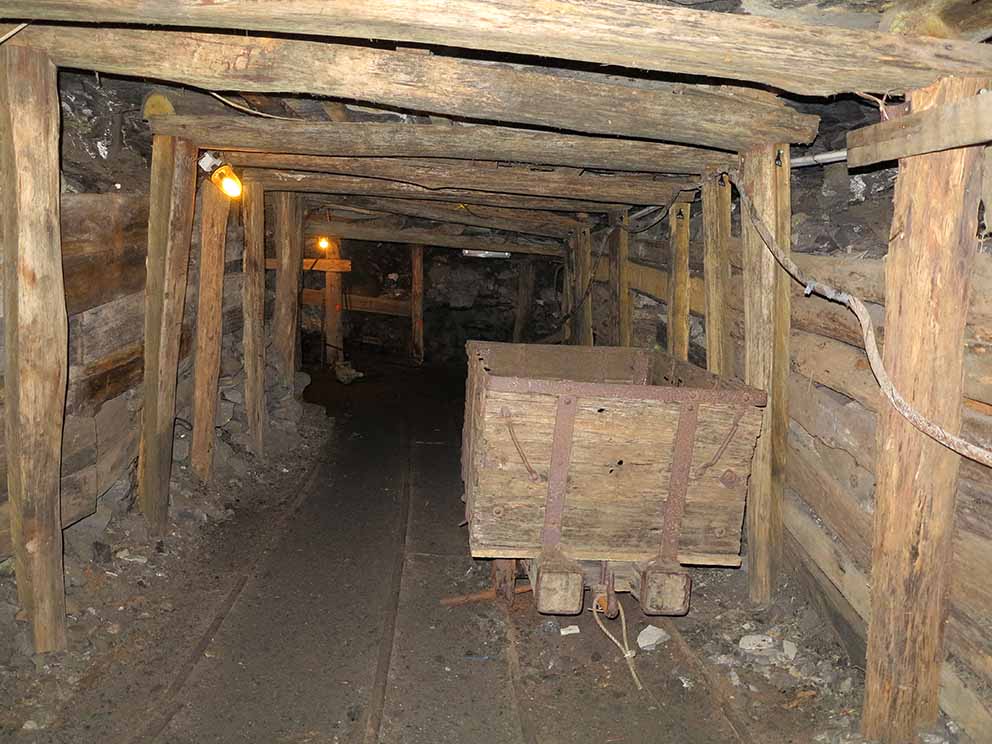

| We assembled with about 15 other people of various ages in a weatherboard building with maps of the extensive workings of the coalfields that cover a staggering 4,828 kilometres of underground tunnels. We were instructed to select a hard hat which, as we put them on, was like getting into costume for a theatre show. I felt a sense of drama fill the room. Our tour guide was Steve Harrop whose enthusiasm had us enthralled from the start. Two small children stared up at Steve, wide-eyed, completely absorbed. We entered the tunnel and I snapped a photo of Mum as she turned to me and said, “My father would be horrified to think I had to pay to come down here”. Dad strode ahead, at 86 undaunted by the steep descent. We took hold of the handrail and made our way down into the gloom. We followed quietly in single file until our guide Steve stopped for the group to gather round for a run-down of the workings of the mine. How the men tunnelled through solid sandstone, worked in virtual darkness, sometimes laboured in water all day long. How they endured constant danger of rockfalls, explosions and poisonous gases that could kill. Small lamps on the walls provided a dim light for us to see but carbide headlamps were the only source of light for my grandfather and his fellow miners. The naked light of a carbide lamp combined with methane gas and coal dust is believed to be the cause of the tragic explosion of February 1937 at No. 20 Shaft in which 13 men were killed. Grandad’s carbide lamp was his only keepsake of 42 years in the mine. That piece of equipment was vital to his life underground but, at the same time, could have led to his death. Every ten metres or so we saw ‘manholes’, sections of rock cut away for several men to shelter when a blast was set off or if there was a rockfall. Heavy posts and beams of local messmate timber stabilised the roof of the manholes and secured vast sections of the tunnel. There was a section where low timber struts appeared to hold up massive rock for miners to work beneath and I shuddered to think of the fate of a miner if the rock gave way. When Steve Harrop pointed to a narrow opening beyond a jumble of rock and coal and explained how miners had to crawl on their stomachs through such small spaces with barely room to swing their picks, I thought of Grandad down there in the dark, day after day. No wonder he didn’t want his young daughter to see where he worked. I thought of Grandma and wondered whether she worried every day or found a way to put the fear away. A glimmering wall of shiny black rock sparked a memory for Mum. “When Mum got a load of coal she’d be going crook if it wasn’t the good shiny stuff. The shiny stuff burnt beautiful down to ash. The other stuff was heavier and didn’t burn well.” Wonthaggi’s black coal was the good stuff that powered up Victoria’s economy and kept it running for the best part of 60 years. |

But the State Coal Mine is more than memories; it is part of the spirit of the town. With its extraordinary history of co-operation and resilience and its authentic old energy heritage, the State Coal Mine might just be the perfect place to demonstrate, educate and help power up Victoria’s new energy future.