IT IS low tide on a crisp, clear winter’s morning in the small fishing village of Rhyll. Blinding sunlight fills the space between French Island and this quiet, sheltered shore on the north-east tip of Phillip Island. The Bass Hills are still smudged with morning mist on the other side of the bay. The receding tide has left behind a patchwork of green seagrass meadows, expanses of deep blue water, luminous sheets of pale blue and a myriad of puddles and pools.

Black swans feed in shallow pools among the seagrass beds, their elegant necks curved into the water to feed. Twenty or thirty ducks skim the surface of the shallows, sweeping their heads from side to side, scooping food into their beaks.

A pelican glides down with massive wings outstretched then skis across a large pool until it comes to a halt. It thrusts its long beak and whole head beneath the water again and again, eagerly hunting for food. Soon two more pelicans arrive to join in.

Floodlit by the morning sun, sacred ibis shine like headlights moving slowing across a watery meadow prodding their curved bills into the mud. Six pied cormorants preen themselves on the metal struts of a small boat moored nearby.

Two red buoys float alone on the water waiting for their boat to return. A local tourist boat motors slowly out of port, following the channel marked by tall red and green navigational posts.

A vehicle with a boat in tow reverses down the boat ramp. Two children chase each other, happily screaming and shouting as their father prepares the boat. There are no queues today but in summer Rhyll is a busy launching place for anglers heading to the popular fishing grounds of Western Port.

Around the corner from the boat ramp is the jetty and out on the water are dozens of sailing boats at anchor, a pretty sight in bright colours of orange, purple, blue and white.

At the jetty, a fisherman walks around the deck of a handsome blue and white commercial fishing boat, hauling in ropes and checking his gear as he prepares to set out to sea.

Out of the blue, several masked lapwings rise up in the air disrupting the quiet with their raucous call. Swans lift their heads in alarm, then seeing no threat, lower their heads into the water again.

Beyond the jetty, where the tide has drained the water away, several boats lean to one side, stranded on the mudflat.

The broad mudflat at the end of the beach is backed by a fringe of mangroves where a white-faced heron struts along in search of food. Out on the open mudflat another heron is barely visible, its blue-grey body, white face and yellow legs well-camouflaged against the motley mud.

The wide grassy embankment above the beach is lined with common reeds. From here you can see the clear line that divides the sandy beach from the rich, brown mudflat. Across the water in the distance is Churchill Island and the township of San Remo.

The shoreline curves around a sweeping bay to Long Point at the edge of the Churchill Island Marine National Park, one of three marine national parks in Western Port where fishing is illegal. These areas are set aside to protect examples of the habitats of Western Port.

The bay’s mangroves, intertidal mudflats, sandflats, saltmarshes, seagrass beds, deep channels and sandy beaches support a rich diversity of birds and fish and are internationally recognised as a Ramsar Wetland for the protection of migratory wading birds.

Rhyll’s position, protected from ocean waves and strong south-westerly winds provides perfect conditions for these wetland habitats and may also explain why Rhyll is the site of Phillip Island’s earliest European habitation.

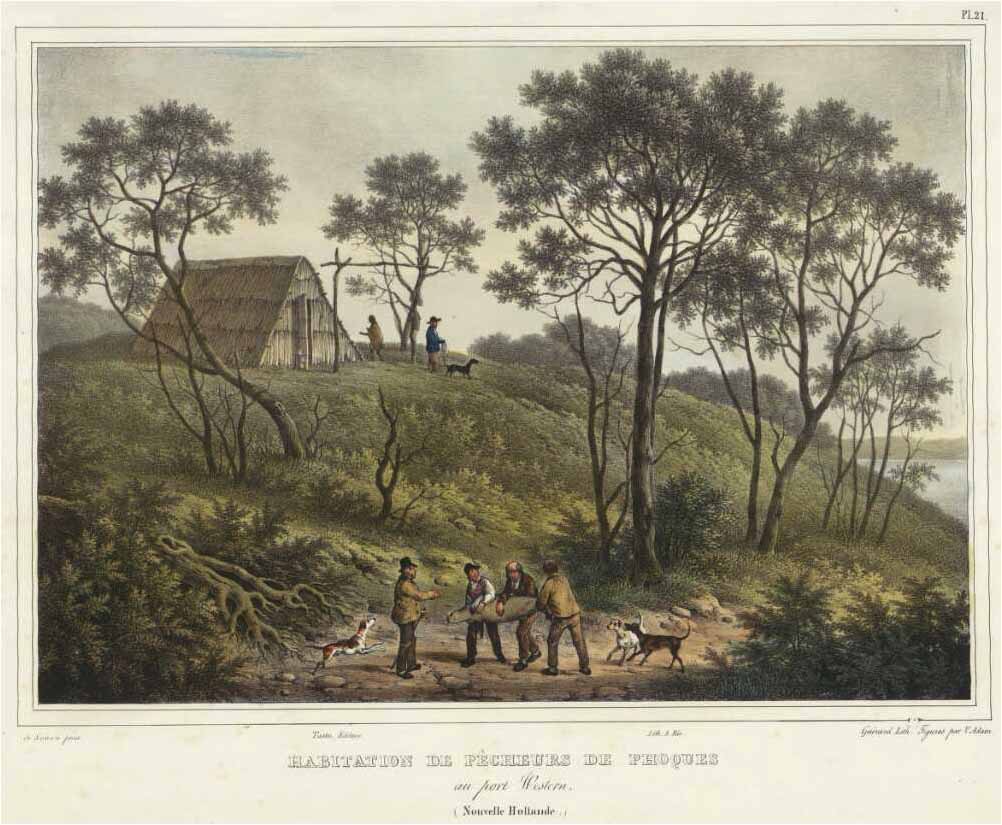

Rhyll was also the site chosen for the establishment of a temporary British settlement (Fort Dumaresq) in 1826. Governor Darling at Sydney Cove was concerned the French might be thinking of annexing territory so ordered posts to be occupied along the southern coast of Australia. Captain D’Urville had just left Western Port when an expedition arrived at Rhyll to erect a flagstaff, hoist the British flag and claim formal possession in the name of the British Crown. Around a year later, the settlement was abandoned for the more reliable water supply at Corinella.

In the 1850s, when the McHaffie family leased the whole of Phillip Island as a pastoral run, an oyster industry developed in Western Port. In the waters off Rhyll, up to 30 boats under sail dredged for oysters for sale to the goldfields. The Rhyll oyster fishers established a village of well-built cottages with neat fences and fruit trees but by 1862, the oyster grounds had been destroyed by silting and overfishing and the village was deserted.

The visits of Lieutenant Grant, Captain D’Urville as well as that of Frenchman Captain Baudin in 1802 and the European discovery of Western Port by George Bass in 1798 are commemorated by the tall monument near the large cypress tree behind the jetty. The low brick well nearby is thought to have been sunk by Captain Wetherall in 1826.

Captain John Barnard Lock and his wife Elizabeth are also remembered here as early settlers of Rhyll. From the 1850s, Captain Lock operated coastal traders around Western Port and beyond then took up permanent residence here in 1869, the year after land on Phillip Island was first opened up for sale.

I return to the waterfront at the end of Lock Road where two little girls in gumboots are wandering across the sandflat collecting seashells from the shore. The incoming tide has now covered the seagrass beds and swallowed the deeper pools. The sheet of bright sunlight has shifted across the bay. From the edge of these sheltered waters it seems that whatever changes a day may bring, the quiet ambience of Rhyll will always remain the same.