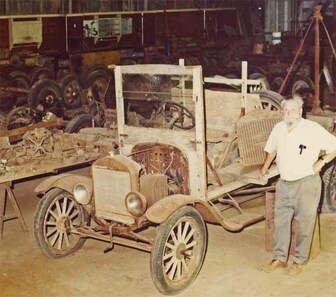

Fred Webb in his shed, now used by Wonthaggi Secondary College.

Fred Webb in his shed, now used by Wonthaggi Secondary College. By Carolyn Landon

This is the story of a man whose cleverness and energy helped to shape Wonthaggi. Fred Webb hasn’t been around since 1985, but his presence is felt every day when the mine whistle blows in the middle of town to signal midday, or whenever anyone passes “Webb’s Shed” in McKenzie Street.

This essay is based on a speech Fred gave about his life in Wonthaggi called “A Young Man and his Truck”, plus additional information taken from an essay, Red Wonthaggi, by Carol Cox (Bass Coast Post, November 1, 2014), and Kit Sleeman's explanation of red stone in his PLOD essay Drains (June 6, 2016).

This is the story of a man whose cleverness and energy helped to shape Wonthaggi. Fred Webb hasn’t been around since 1985, but his presence is felt every day when the mine whistle blows in the middle of town to signal midday, or whenever anyone passes “Webb’s Shed” in McKenzie Street.

This essay is based on a speech Fred gave about his life in Wonthaggi called “A Young Man and his Truck”, plus additional information taken from an essay, Red Wonthaggi, by Carol Cox (Bass Coast Post, November 1, 2014), and Kit Sleeman's explanation of red stone in his PLOD essay Drains (June 6, 2016).

Fred Webb came to Wonthaggi in the early 1930s to work for the State Coal Mine as a road builder, but once his mechanical know-how was recognised he was put in charge of the transition from horse teams to tractors and trucks, and thereafter, given responsibility for all mine transport. This included "par buckling” (rolling heavy boilers through tea tree swamps as the first step in road-making) and spreading the stone from the huge mine stone dumps.

After a while, according to Fred, "It was decided that the roads were good enough to start bussing children to school in Wonthaggi. So, I started with one small bus, but as roads improved and more families were in the district, we needed more buses. I finished with nine large buses and the routes were often stopped by the flooded Powlett River in those days. On the Dalyston, Korumburra and Kongwak roads, the parents would meet the buses with horse and cart on each side of the river.”

When he saw that Fred was building his own buses, the mine manager asked him to transport the miners to and from the mines. A powerful memory in Wonthaggi is of those buses moving through the streets of Wonthaggi for the different mine shifts.

The mine manager asked Fred to build a long distance high-pressure steam pipeline from the Powerhouse to the hospital, which he did after a great deal of creative thinking. The result was a system that was considered unique in Victoria in those days.

Just after World War II, the Cyclone Company asked Fred to build its large factory in Wonthaggi as part of the Government's decentralisation project. Since new materials were almost unprocurable then, Fred used large mine buildings standing idle near worked-out pits. They had to be secured on deep drop-hammer foundations, a continuous pour requiring all the cement at hand to achieve the goal.

Getting large quantities of cement was impossible in Victoria at that time. Undaunted, Fred went to San Remo and hired boats from the fishing fleet, then sailed to Devonport in Tasmania and back again with the cement.

"The State Government takes me out to dinner, but the Federal Government was after my scalp,” said Fred.

"Turns out we need more cement, so we take the fishing fleet to Tassie again. When we start the pour, we had four concrete mixers, eight wheelbarrows and thirty men all day and into the night. It's hurricane lamps everywhere. The men were so tired, and so hungry, so Muggins runs the rabbit – as it is known – beer and sandwiches, trip after trip, Taberners (the Whalebones Hotel) to factory until the job is finished. Taberners saved the day.”

Fred turned his mind to the coal mine slag heaps.

As Kit Sleeman explained in his essay Drains, "The waste dumps from the coal mines contained mainly mudstone, but also splint, which is mudstone with a high carboniferous content, and also coal. There was also wood waste and oily waste mixed in. Eventually, the combustible material self-combusts and the whole mountain of waste slowly smoulders: smoke oozes from the ground, where there are hot-spots with embers and flame and there is a sulphurous stench. In fact, crystals of pure sulphur can be seen growing at the edges of vents emitting smoke.

"The heat from this combustion roasts the mudstone which is grey and relatively soft, but after burning it is brick-hard and brick-red. So the waste dumps were allowed to burn for a few decades and were then quarried and crushed to suitable pebble size.”

John Bordignon told Carol Cox the dumps didn't just smoulder but at times also had flames coming from them. He said the Western Area dump was used as a beacon for fishermen to get their bearings in the dark. And that burning dumps would help pilots flying from Tasmania to confirm their position. His mother told him she remembered coming into Wonthaggi by train, and seeing the glowing dumps told her she was getting close to home.

John believed there was an unsuccessful attempt to extinguish the dumps during the Second World War as they contravened “no lights visible” rule of the blackout.

Late in the 1930s, a Powlett Express article about “Red Stone Raiders” talked about “private persons persist[ing] in helping themselves to the Council’s crushed stone at the mine dumps. The State, which controlled the mines, had gifted the operation of the Eastern Area to the Borough Council, but it was left unfenced and uncontrolled until after the war when Fred asked, “What can we do with the huge mine stone dumps? Millions of tons just burning away for the past twenty years or more? Perhaps crushing it would turn it into something valuable!”

He got permission to establish a stone crushing plant. According to Carol, although Fred did not have a formal contract with the council, “just a minute on the books giving him permission to operate the crusher at the stone dump for which he paid threepence per cubic yards for stone he sold to private contractors.” He also sold crushed stone to the Council at a discount price. The Council was of the opinion that with crushing and labour costs they would make no profit if they operated the dump themselves.

So Fred got the job. He built the crusher himself, had the crushed stone tested by the Country Roads Board who found it was OK, and then he’s open for business. “Everyone wants it,” he said. “There were over 30 trucks carting six days a week.” The Herald did a half page feature Wonthaggi redstone in Wonthaggi industry begins.” Highways from Wonthaggi to Tooradin, Loch, Leongatha and many hundreds of shire and borough roads were all built of Wonthaggi red stone.

“Millions of tons, and million of dollars paid in wages, cartage and royalties. We have a lot to thank the State Government for besides coal,” he was fond of saying.

In the mid-50s the big news was that Melbourne was to have the Olympic Games. Fred jumped at the announcement: “So, nice letters to Minister Kent Hughes: ‘All fine red stone for the games - free at crusher in Wonthaggi.’”

“‘This should help Wonthaggi along’ thinks a government member, but not so. Nice letter back, thanks, etc., but government experts have ascertained no suitable material in Australia, so it is ordered from England.

“A cabinet leak. Yes! Back in ’56 a professor Bill Rawlinson, President of Melbourne University Athletic Club with fellow professor come to Wonthaggi to see the red stone. It is the very thing, so trucks start carting day and night to the Beaurepaire One-Million-Pound Sporting Complex at Melbourne University sports oval.

The track is finished and the world-renowned coach, Franz Stamphl, says it is the best! So visiting world athletes converge on University running track - 100% Wonthaggi red stone.

“The grapevine is at work and the Minister, Kent Hughes, also comes to Wonthaggi. He has a long story to tell, but much secrecy, please. The imported material is not so good. ‘We are a bit behind schedule,’ he says. ‘The press is a bit critical, but how much and how fast can you get the same stone as the University track to the Melbourne Cricket Ground and Olympic Village?

“So! The world’s best athletes set world records on Wonthaggi red stone. It is a story I think should be told, and I am unashamedly proud of it.”

This essay was first published in The Plod, the magazine of the Wonthaggi & District Historical Society.

After a while, according to Fred, "It was decided that the roads were good enough to start bussing children to school in Wonthaggi. So, I started with one small bus, but as roads improved and more families were in the district, we needed more buses. I finished with nine large buses and the routes were often stopped by the flooded Powlett River in those days. On the Dalyston, Korumburra and Kongwak roads, the parents would meet the buses with horse and cart on each side of the river.”

When he saw that Fred was building his own buses, the mine manager asked him to transport the miners to and from the mines. A powerful memory in Wonthaggi is of those buses moving through the streets of Wonthaggi for the different mine shifts.

The mine manager asked Fred to build a long distance high-pressure steam pipeline from the Powerhouse to the hospital, which he did after a great deal of creative thinking. The result was a system that was considered unique in Victoria in those days.

Just after World War II, the Cyclone Company asked Fred to build its large factory in Wonthaggi as part of the Government's decentralisation project. Since new materials were almost unprocurable then, Fred used large mine buildings standing idle near worked-out pits. They had to be secured on deep drop-hammer foundations, a continuous pour requiring all the cement at hand to achieve the goal.

Getting large quantities of cement was impossible in Victoria at that time. Undaunted, Fred went to San Remo and hired boats from the fishing fleet, then sailed to Devonport in Tasmania and back again with the cement.

"The State Government takes me out to dinner, but the Federal Government was after my scalp,” said Fred.

"Turns out we need more cement, so we take the fishing fleet to Tassie again. When we start the pour, we had four concrete mixers, eight wheelbarrows and thirty men all day and into the night. It's hurricane lamps everywhere. The men were so tired, and so hungry, so Muggins runs the rabbit – as it is known – beer and sandwiches, trip after trip, Taberners (the Whalebones Hotel) to factory until the job is finished. Taberners saved the day.”

Fred turned his mind to the coal mine slag heaps.

As Kit Sleeman explained in his essay Drains, "The waste dumps from the coal mines contained mainly mudstone, but also splint, which is mudstone with a high carboniferous content, and also coal. There was also wood waste and oily waste mixed in. Eventually, the combustible material self-combusts and the whole mountain of waste slowly smoulders: smoke oozes from the ground, where there are hot-spots with embers and flame and there is a sulphurous stench. In fact, crystals of pure sulphur can be seen growing at the edges of vents emitting smoke.

"The heat from this combustion roasts the mudstone which is grey and relatively soft, but after burning it is brick-hard and brick-red. So the waste dumps were allowed to burn for a few decades and were then quarried and crushed to suitable pebble size.”

John Bordignon told Carol Cox the dumps didn't just smoulder but at times also had flames coming from them. He said the Western Area dump was used as a beacon for fishermen to get their bearings in the dark. And that burning dumps would help pilots flying from Tasmania to confirm their position. His mother told him she remembered coming into Wonthaggi by train, and seeing the glowing dumps told her she was getting close to home.

John believed there was an unsuccessful attempt to extinguish the dumps during the Second World War as they contravened “no lights visible” rule of the blackout.

Late in the 1930s, a Powlett Express article about “Red Stone Raiders” talked about “private persons persist[ing] in helping themselves to the Council’s crushed stone at the mine dumps. The State, which controlled the mines, had gifted the operation of the Eastern Area to the Borough Council, but it was left unfenced and uncontrolled until after the war when Fred asked, “What can we do with the huge mine stone dumps? Millions of tons just burning away for the past twenty years or more? Perhaps crushing it would turn it into something valuable!”

He got permission to establish a stone crushing plant. According to Carol, although Fred did not have a formal contract with the council, “just a minute on the books giving him permission to operate the crusher at the stone dump for which he paid threepence per cubic yards for stone he sold to private contractors.” He also sold crushed stone to the Council at a discount price. The Council was of the opinion that with crushing and labour costs they would make no profit if they operated the dump themselves.

So Fred got the job. He built the crusher himself, had the crushed stone tested by the Country Roads Board who found it was OK, and then he’s open for business. “Everyone wants it,” he said. “There were over 30 trucks carting six days a week.” The Herald did a half page feature Wonthaggi redstone in Wonthaggi industry begins.” Highways from Wonthaggi to Tooradin, Loch, Leongatha and many hundreds of shire and borough roads were all built of Wonthaggi red stone.

“Millions of tons, and million of dollars paid in wages, cartage and royalties. We have a lot to thank the State Government for besides coal,” he was fond of saying.

In the mid-50s the big news was that Melbourne was to have the Olympic Games. Fred jumped at the announcement: “So, nice letters to Minister Kent Hughes: ‘All fine red stone for the games - free at crusher in Wonthaggi.’”

“‘This should help Wonthaggi along’ thinks a government member, but not so. Nice letter back, thanks, etc., but government experts have ascertained no suitable material in Australia, so it is ordered from England.

“A cabinet leak. Yes! Back in ’56 a professor Bill Rawlinson, President of Melbourne University Athletic Club with fellow professor come to Wonthaggi to see the red stone. It is the very thing, so trucks start carting day and night to the Beaurepaire One-Million-Pound Sporting Complex at Melbourne University sports oval.

The track is finished and the world-renowned coach, Franz Stamphl, says it is the best! So visiting world athletes converge on University running track - 100% Wonthaggi red stone.

“The grapevine is at work and the Minister, Kent Hughes, also comes to Wonthaggi. He has a long story to tell, but much secrecy, please. The imported material is not so good. ‘We are a bit behind schedule,’ he says. ‘The press is a bit critical, but how much and how fast can you get the same stone as the University track to the Melbourne Cricket Ground and Olympic Village?

“So! The world’s best athletes set world records on Wonthaggi red stone. It is a story I think should be told, and I am unashamedly proud of it.”

This essay was first published in The Plod, the magazine of the Wonthaggi & District Historical Society.