Phillip Island Cemetery. Photo: Geoff Ellis

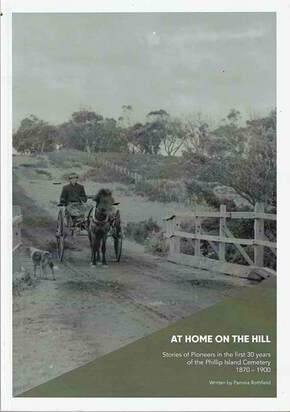

Phillip Island Cemetery. Photo: Geoff Ellis Pamela Rothfield’s meticulous history of the first 73 occupants of the Phillip Island cemetery provides a moving snapshot of this fledgling society: the vulnerability of babies, children and pregnant women, the prevalence of depression, the high rate of death by accident.

Copies of At Home on the Hill are on sale at $35 through the Rhyll General Store, the Phillip Island and District Historical Society and the Phillip Island Cemetery Trust, PO Box 8045, Rhyll, VIC 3923. The book is also available for borrowing from the Cowes Library.

Copies of At Home on the Hill are on sale at $35 through the Rhyll General Store, the Phillip Island and District Historical Society and the Phillip Island Cemetery Trust, PO Box 8045, Rhyll, VIC 3923. The book is also available for borrowing from the Cowes Library. By Pamela Rothfield

IN 1869, the year after Phillip Island was opened to selection, George and Catherine Smith arrived in Rhyll to start a new life. Within a year, their little daughter, Mary, succumbed to dysentery. She was a mere 20 months old.

Although land had been earmarked for a cemetery on the island, it had yet to officially open. This meant that George had to sail to Hastings and then walk to Mornington to obtain authorisation to prepare a grave for his daughter.

Once the permit was in his calloused hand he promptly walked back to Hastings and then sailed back to the Island to perform his sad duty.

In Phillip Island in Picture and Story, Joshua Wicket Gliddon noted that, at the time, "No roads or even tracks existed between the Smith home and the place of burial, which left no other way for him but to carry the casket on his shoulder, for a distance of two miles, through country that was mostly dense scrub. Having arrived, there was then the labour of digging a grave, the first in the Phillip Island Cemetery."

My interest in history, or more accurately genealogy, started just on 30 years ago. My first son’s name was drawn from the patriarchal side of the family. When it was time to name my second son, I quizzed my mother as to the names of my grandmother: Charlotte Ellen Blake Cleeland.

Blake!

My mother wasn’t really sure where that name had come from but she’d heard, somewhere, that there was a connection to the great Admiral Robert Blake. Er, hem, arh – well, although in subsequent years this has turned out to be incorrect, nevertheless, I chose to name my baby Blake.

I then set about researching this family and its history.

In those days there was no internet or ancestry.com or even email – everything had to be done in person, viewing endless microfiche reels and sending letters with a postal note enclosed to cover the cost of whatever document one was seeking. All this was followed by a number of trips to the UK to tread the soil of my ancestors in person.

The more I discovered, the more I delved and the more I delved, the more I discovered. Over these 30 years I have collected many family stories, which I preserved in booklets and distributed at family reunions over the years, in the hope that the next generation will find a connection with their ancestors.

On taking over the responsibilities of the Phillip Island Cemetery Trust some 14 years later, I started researching a number of the more well-known “occupants” of the cemetery.

I led a few walking tours of some of the graves and found there was great interest in these walks and a desire to know more about our pioneers and the lives they had led.

Those early years on Phillip Island were certainly daunting. There were no roads, no medical attendance; water was scarce. The pioneers were hardy and faced countless challenges and often tragedy.

I soon discovered that many descendants of other Island pioneer families also had stories and information, which have been passed down through generations. I felt compelled to preserve these histories and bring them together so they could be shared with today’s Islanders.

So, about four years ago, I decided to research then document the lives of these early Cemetery occupants. The Trust’s earliest records were a bit sketchy; however, contact with the Justice department soon corrected and expanded our information.

As the number of personal histories accumulated, I realised that a book was there to be written. A book that called out to me to write it, even though I am no writer, journalist or academic. I am not gifted with the art of expression, descriptive adjectives or imagination – I just love local history, I love Phillip Island and I love our Cemetery.

My book is a simple glimpse into the lives of 73 people who lived and died on Phillip Island between 1870 and 1900. These 73 individuals are all buried in the Phillip Island Cemetery.

I hope that I have captured the spirit of those times and the lives of those pioneers who came to Phillip Island, looking for an opportunity for an improved life.

Their names are dotted around the Island - remembered in street signs, beaches and other landmarks like the Forrests, Richardsons, McIlwraiths, Jenners, Sunderlands, Smiths, Reids, Waltons Wests. They all have a story to tell. And I have written a book!

IN 1869, the year after Phillip Island was opened to selection, George and Catherine Smith arrived in Rhyll to start a new life. Within a year, their little daughter, Mary, succumbed to dysentery. She was a mere 20 months old.

Although land had been earmarked for a cemetery on the island, it had yet to officially open. This meant that George had to sail to Hastings and then walk to Mornington to obtain authorisation to prepare a grave for his daughter.

Once the permit was in his calloused hand he promptly walked back to Hastings and then sailed back to the Island to perform his sad duty.

In Phillip Island in Picture and Story, Joshua Wicket Gliddon noted that, at the time, "No roads or even tracks existed between the Smith home and the place of burial, which left no other way for him but to carry the casket on his shoulder, for a distance of two miles, through country that was mostly dense scrub. Having arrived, there was then the labour of digging a grave, the first in the Phillip Island Cemetery."

My interest in history, or more accurately genealogy, started just on 30 years ago. My first son’s name was drawn from the patriarchal side of the family. When it was time to name my second son, I quizzed my mother as to the names of my grandmother: Charlotte Ellen Blake Cleeland.

Blake!

My mother wasn’t really sure where that name had come from but she’d heard, somewhere, that there was a connection to the great Admiral Robert Blake. Er, hem, arh – well, although in subsequent years this has turned out to be incorrect, nevertheless, I chose to name my baby Blake.

I then set about researching this family and its history.

In those days there was no internet or ancestry.com or even email – everything had to be done in person, viewing endless microfiche reels and sending letters with a postal note enclosed to cover the cost of whatever document one was seeking. All this was followed by a number of trips to the UK to tread the soil of my ancestors in person.

The more I discovered, the more I delved and the more I delved, the more I discovered. Over these 30 years I have collected many family stories, which I preserved in booklets and distributed at family reunions over the years, in the hope that the next generation will find a connection with their ancestors.

On taking over the responsibilities of the Phillip Island Cemetery Trust some 14 years later, I started researching a number of the more well-known “occupants” of the cemetery.

I led a few walking tours of some of the graves and found there was great interest in these walks and a desire to know more about our pioneers and the lives they had led.

Those early years on Phillip Island were certainly daunting. There were no roads, no medical attendance; water was scarce. The pioneers were hardy and faced countless challenges and often tragedy.

I soon discovered that many descendants of other Island pioneer families also had stories and information, which have been passed down through generations. I felt compelled to preserve these histories and bring them together so they could be shared with today’s Islanders.

So, about four years ago, I decided to research then document the lives of these early Cemetery occupants. The Trust’s earliest records were a bit sketchy; however, contact with the Justice department soon corrected and expanded our information.

As the number of personal histories accumulated, I realised that a book was there to be written. A book that called out to me to write it, even though I am no writer, journalist or academic. I am not gifted with the art of expression, descriptive adjectives or imagination – I just love local history, I love Phillip Island and I love our Cemetery.

My book is a simple glimpse into the lives of 73 people who lived and died on Phillip Island between 1870 and 1900. These 73 individuals are all buried in the Phillip Island Cemetery.

I hope that I have captured the spirit of those times and the lives of those pioneers who came to Phillip Island, looking for an opportunity for an improved life.

Their names are dotted around the Island - remembered in street signs, beaches and other landmarks like the Forrests, Richardsons, McIlwraiths, Jenners, Sunderlands, Smiths, Reids, Waltons Wests. They all have a story to tell. And I have written a book!