Three generations of Terri Allen's family have lived in Frog Hollow, on the outskirts of Wonthaggi.

By Terri Allen

IN 1909 and 1910 men flocked to the Powlett Field built on an area called The Clump to work at the new State Coal Mine. Many of them had relocated from the goldmining areas of Ballarat, Creswick and Allendale. One was my grandfather, Cliff Gitsham.

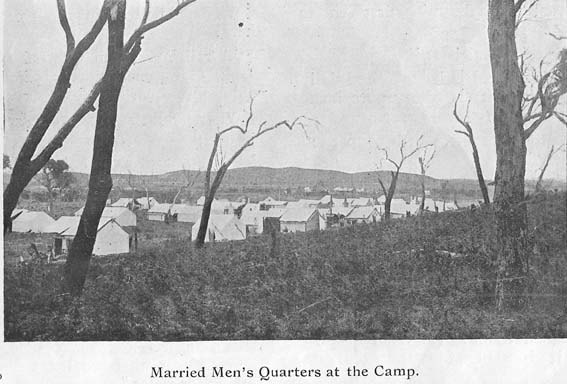

To accommodate this influx of men the government supplied and erected tents on two acres cleared of swamp paperbark opposite the site of today’s hospital in Wonthaggi. Four hundred tents and a few wooden buildings knew only the tramp of male feet… As women arrived, a separate section was established for the married men’s quarters. Cliff, previously waited on hand and foot by his doting mother and sisters, must have had a hard time batching, but when his sister arrived things would have been easier.

In September 1910 the model town of Wonthaggi was proclaimed after having been laid out on land bought by the state government from the grazing leases of Hollis, Scott and Heslop. By July 1910, tent town was deserted and those miners without recourse to a house in the newly established town upped tents and moved away from the swampy Tent Town to the drier, sandier environment of Flea Hill (today’s Easton Street). By then the town’s population was 4000 and rising. It had roads, footpaths, and Lance Creek Reservoir, which would supply water to the town, was being made. In 1915, when this story of Frog Hollow really begins, the town consisted of a post office, state school, six churches, two banks, police station, two newspapers, several coffee palaces, and boarding houses, public hall, picture theatre and skating rink.

Miner WJG (Jack) Brown built a house at the bush end of the newly extended Broome Crescent and soon thereafter moved his family – most importantly for this story his daughter Eva – to town. Cliff Gitsham soon began courting Eva Brown and then bought a block adjoining the Browns’ block for £8. It was a flat quarter acre block of virgin bush with nearby sand ridges and a string of froggy pools. Messmate stringybark, scrub sheoak, swamp paperbark, spreading roperush, common reed, long purple flag and dagger hakea covered the block. Eva’s father, Jack, helped Cliff to clear the house site by hand. And Cliff set about building a house.

Set on the outskirts of town, the house had a view of distant dunes and was serenaded by the thunder of pounding surf. All the streets were unlit and surfaces were rough, so any evening social occasion involved wearing boots and carrying good shoes and taking a lantern.

By the time Cliff made the final payment for his block of land in 1921, he had built a two-roomed dwelling running east and west, its inner walls packing cases, floors wooden and with a chimney on the west side. Bag mats, curtains, jam jars of wild flowers and family photos were the only things to relieve its stark utilitarianism. Essential conveniences were buckets (all water had to be carted from the spring at Tank Hill a half mile away), a metal tub (for washing in front of the fire), a post and prop clothes line strung across the backyard, the coal heap (essential fuel), the woodshed (for dry kindling), the lavatory on the western side of the backyard and gradually established ash paths.

At first the eastern room was the bedroom while western one was the living room. Here the family ate, relaxed and bathed. All cooking had to be done over the open fire in black cast iron cooking pots: frying pan, kettle, saucepans, camp oven. Lighting was provided by kerosene lamps and a pit lamp for night excursions through the backyard. The powerhouse had been established in 1912, but it took a long time for power to reach the outskirts of town.

As Cliff and Eva became more established, they added lino and cut-out paper doyleys for mantel edges to the living room, which was dominated by a huge scrubbed wooden table and wooden chairs. Against one wall was a homemade wooden dresser. Outside was the meat safe hanging from a branch and a wooden bench. There were two cut V-shaped kerosene tins used for dishes, washing and bathing babies.

While the bedroom was finished with a double bed, chest of drawers, dressing table and crib, the growing family over-flowed into the living room where they were housed in a curtained nook.

Soon extensions were needed and the two-roomed house expanded to four rooms. The back western room became the girls’ bedroom. (Today its polished Baltic pine floorboards are marred by a deep char mark bearing witness to the fire started by one child to warm another.) Its eastern counterpart was the kitchen. This room boasted a coal stove with oven and was reached by a porch way, which had a tap from the newly installed tank. A Coolgardie safe kept food cool and fresh. Opposite the kitchen window was the washhouse, a wooden construction used to store carbide, supplies, garden tools, and stone wash troughs that complemented the copper, which remained outside. In this coal-fired convenience oodles of hot water for bathing and washing clothes, especially filthy pit clothes, was boiled. It was also in this kettle where crayfish, which were plentiful back then, were boiled.

Gradually the yard took shape, its fences a barrier to wandering stock and animals, while keeping little girls inside. The western side was wire netting festooned with dolichos; the other fences were picket with three study wooden gates, front, middle and back. Between Browns’ and Gitshams’ was a walkway used weekly by the night man.

Huge trees shaded the backyard: gums either side of the back gate, two at the present clothesline site, and three more; often these trees provided food for itinerant koalas and flocks of honeyeaters, not to mention Christmas beetles in summer and bull ants. Where the chook pen ran at the top end of the yard, there was teatree, while scrub sheoak and native cherries grew along the side fence. As soon as the yard was cleared it became infested with bracken and high grass, which necessitated the wearing of boots in the winter.

An effort was made to establish two gardens: a small vegetable plot not far from the sheltering cypress someone at some time planted in the south-west corner of the front yard in an attempt to hinder the prevailing westerlies in their onslaught on the flimsy dwelling; and a flowerbed either side of the front gate. Often Eva’s flower garden was a blaze of colour, a mass of waving poppies.

Beyond the side fence, despite its impressive title of Chambers Street, lay thick scrub, an enchanted realm of teatree, wiry-grass tunnels, bracken, gums and shrubs. Almost opposite the back gate was a sandpit, just right for digging in and creating shelves and hidey-holes, however dangerous in hindsight. Tantalisingly beckoning lay “The Hill” with its scrub, winding tracks and sand pockets, playground to scores of children. (And onwards for decades to come!) At its base was a chain of ponds, home of tadpoles, insects, frogs, yabbies, and, of course, leeches. For some strange reason snakes were never sighted. Next to the ponds was “The Flat”.

Without material possessions, the children entertained themselves weaving intricate fantasies using the environment. Some of the games they played were Charlie-over-the-water, kick-the-tin, and hide-and-seek, most of which were played in Broome Crescent. “The Flat” was used for games of cricket and the annual bonfire on Guy Fawkes Night. Gutter clay was collected and moulded into primitive pots, which were dried in the oven for use in the cubbies dotting the scrub.

Toys were simple and home-made: jam-tin stilts, stick stilts, swords, bows and arrows, jacks from the shanks, brown paper kites with rag tails, skipping ropes, allies (often the glass marble from lemonade bottles), blackboard, chalk and pencils. Dolls were, in the main, celluloid baby dolls or tiny china dolls for which the girls made clothes. Perhaps the greatest gift each Christmas was a book.

These early days in Wonthaggi were tough with a bracing climate ruled by westerlies off Bass Strait, a regimen of back-breaking work in primitive conditions, the ever-present fear of the mine whistle heralding disaster and a time of intermittent strikes when miners fought for safe working conditions and security. The Gitsham family territory was hemmed in by relatives. As a neighbourhood it was tight-knit, succouring the young family.

The street was a tangle of teatree and a swamp, fittingly dubbed “Frog Hollow”. To cross the street, the pedestrian had to negotiate a narrow bridge over a main drain and stepping stones across Frog Hollow.

IN 1909 and 1910 men flocked to the Powlett Field built on an area called The Clump to work at the new State Coal Mine. Many of them had relocated from the goldmining areas of Ballarat, Creswick and Allendale. One was my grandfather, Cliff Gitsham.

To accommodate this influx of men the government supplied and erected tents on two acres cleared of swamp paperbark opposite the site of today’s hospital in Wonthaggi. Four hundred tents and a few wooden buildings knew only the tramp of male feet… As women arrived, a separate section was established for the married men’s quarters. Cliff, previously waited on hand and foot by his doting mother and sisters, must have had a hard time batching, but when his sister arrived things would have been easier.

In September 1910 the model town of Wonthaggi was proclaimed after having been laid out on land bought by the state government from the grazing leases of Hollis, Scott and Heslop. By July 1910, tent town was deserted and those miners without recourse to a house in the newly established town upped tents and moved away from the swampy Tent Town to the drier, sandier environment of Flea Hill (today’s Easton Street). By then the town’s population was 4000 and rising. It had roads, footpaths, and Lance Creek Reservoir, which would supply water to the town, was being made. In 1915, when this story of Frog Hollow really begins, the town consisted of a post office, state school, six churches, two banks, police station, two newspapers, several coffee palaces, and boarding houses, public hall, picture theatre and skating rink.

Miner WJG (Jack) Brown built a house at the bush end of the newly extended Broome Crescent and soon thereafter moved his family – most importantly for this story his daughter Eva – to town. Cliff Gitsham soon began courting Eva Brown and then bought a block adjoining the Browns’ block for £8. It was a flat quarter acre block of virgin bush with nearby sand ridges and a string of froggy pools. Messmate stringybark, scrub sheoak, swamp paperbark, spreading roperush, common reed, long purple flag and dagger hakea covered the block. Eva’s father, Jack, helped Cliff to clear the house site by hand. And Cliff set about building a house.

Set on the outskirts of town, the house had a view of distant dunes and was serenaded by the thunder of pounding surf. All the streets were unlit and surfaces were rough, so any evening social occasion involved wearing boots and carrying good shoes and taking a lantern.

By the time Cliff made the final payment for his block of land in 1921, he had built a two-roomed dwelling running east and west, its inner walls packing cases, floors wooden and with a chimney on the west side. Bag mats, curtains, jam jars of wild flowers and family photos were the only things to relieve its stark utilitarianism. Essential conveniences were buckets (all water had to be carted from the spring at Tank Hill a half mile away), a metal tub (for washing in front of the fire), a post and prop clothes line strung across the backyard, the coal heap (essential fuel), the woodshed (for dry kindling), the lavatory on the western side of the backyard and gradually established ash paths.

At first the eastern room was the bedroom while western one was the living room. Here the family ate, relaxed and bathed. All cooking had to be done over the open fire in black cast iron cooking pots: frying pan, kettle, saucepans, camp oven. Lighting was provided by kerosene lamps and a pit lamp for night excursions through the backyard. The powerhouse had been established in 1912, but it took a long time for power to reach the outskirts of town.

As Cliff and Eva became more established, they added lino and cut-out paper doyleys for mantel edges to the living room, which was dominated by a huge scrubbed wooden table and wooden chairs. Against one wall was a homemade wooden dresser. Outside was the meat safe hanging from a branch and a wooden bench. There were two cut V-shaped kerosene tins used for dishes, washing and bathing babies.

While the bedroom was finished with a double bed, chest of drawers, dressing table and crib, the growing family over-flowed into the living room where they were housed in a curtained nook.

Soon extensions were needed and the two-roomed house expanded to four rooms. The back western room became the girls’ bedroom. (Today its polished Baltic pine floorboards are marred by a deep char mark bearing witness to the fire started by one child to warm another.) Its eastern counterpart was the kitchen. This room boasted a coal stove with oven and was reached by a porch way, which had a tap from the newly installed tank. A Coolgardie safe kept food cool and fresh. Opposite the kitchen window was the washhouse, a wooden construction used to store carbide, supplies, garden tools, and stone wash troughs that complemented the copper, which remained outside. In this coal-fired convenience oodles of hot water for bathing and washing clothes, especially filthy pit clothes, was boiled. It was also in this kettle where crayfish, which were plentiful back then, were boiled.

Gradually the yard took shape, its fences a barrier to wandering stock and animals, while keeping little girls inside. The western side was wire netting festooned with dolichos; the other fences were picket with three study wooden gates, front, middle and back. Between Browns’ and Gitshams’ was a walkway used weekly by the night man.

Huge trees shaded the backyard: gums either side of the back gate, two at the present clothesline site, and three more; often these trees provided food for itinerant koalas and flocks of honeyeaters, not to mention Christmas beetles in summer and bull ants. Where the chook pen ran at the top end of the yard, there was teatree, while scrub sheoak and native cherries grew along the side fence. As soon as the yard was cleared it became infested with bracken and high grass, which necessitated the wearing of boots in the winter.

An effort was made to establish two gardens: a small vegetable plot not far from the sheltering cypress someone at some time planted in the south-west corner of the front yard in an attempt to hinder the prevailing westerlies in their onslaught on the flimsy dwelling; and a flowerbed either side of the front gate. Often Eva’s flower garden was a blaze of colour, a mass of waving poppies.

Beyond the side fence, despite its impressive title of Chambers Street, lay thick scrub, an enchanted realm of teatree, wiry-grass tunnels, bracken, gums and shrubs. Almost opposite the back gate was a sandpit, just right for digging in and creating shelves and hidey-holes, however dangerous in hindsight. Tantalisingly beckoning lay “The Hill” with its scrub, winding tracks and sand pockets, playground to scores of children. (And onwards for decades to come!) At its base was a chain of ponds, home of tadpoles, insects, frogs, yabbies, and, of course, leeches. For some strange reason snakes were never sighted. Next to the ponds was “The Flat”.

Without material possessions, the children entertained themselves weaving intricate fantasies using the environment. Some of the games they played were Charlie-over-the-water, kick-the-tin, and hide-and-seek, most of which were played in Broome Crescent. “The Flat” was used for games of cricket and the annual bonfire on Guy Fawkes Night. Gutter clay was collected and moulded into primitive pots, which were dried in the oven for use in the cubbies dotting the scrub.

Toys were simple and home-made: jam-tin stilts, stick stilts, swords, bows and arrows, jacks from the shanks, brown paper kites with rag tails, skipping ropes, allies (often the glass marble from lemonade bottles), blackboard, chalk and pencils. Dolls were, in the main, celluloid baby dolls or tiny china dolls for which the girls made clothes. Perhaps the greatest gift each Christmas was a book.

These early days in Wonthaggi were tough with a bracing climate ruled by westerlies off Bass Strait, a regimen of back-breaking work in primitive conditions, the ever-present fear of the mine whistle heralding disaster and a time of intermittent strikes when miners fought for safe working conditions and security. The Gitsham family territory was hemmed in by relatives. As a neighbourhood it was tight-knit, succouring the young family.

The street was a tangle of teatree and a swamp, fittingly dubbed “Frog Hollow”. To cross the street, the pedestrian had to negotiate a narrow bridge over a main drain and stepping stones across Frog Hollow.

Part II: Domestic Life

THE early days in Wonthaggi were tough with the bracing climate rolling in off Bass Strait, a regimen of back-breaking work in primitive conditions, the ever-present fear of the mine whistle heralding disaster and a time of intermittent strikes when miners fought for safe working conditions and security.

Cliff Gitsham needed to maintain a thriving vegetable garden and fowl yard, as well as become a fisherman and rabbiter, to provide for his family in strike times in the 1920s and especially the 1930s. Cupboards were always well provisioned to tide the family over in such events. Add to this the need to repair and extend the house, shedding and fences, and to keep up fuel supplies and there was little time left for relaxation. However, reading, woodturning local blackwood on a homemade bicycle lathe, and radio after 1930, filled in the gaps. Eva, too, had a heavy workload with washing nappies and pit clothes, preserving, baking, making clothes and rearing children, yet she enjoyed dancing, films, reading and crafts such as embroidery, crocheting, knitting and tatting. The crafts were done over morning tea as the neighbourhood women chatted, swapping recipes, cures and advice – their hands were never idle. It was here they traded produce and pickles, collecting milk from the local cow.

This neighbourhood was close-knit, with people helping each other with jobs and ready to share at all times, a feature of Wonthaggi’s staunch unionism. Workmates rallied in times of need and the tightly bound union town established the co-operative store – butcher, baker, grocer, haberdasher, ironmonger – (family account number: Gitsham G9), which provided help in times of strike and strife.

Although the Gitshams had no car before the war, the whole extended family enjoyed outings walking to the Back Beach a few miles away through the scrub. They joined the train-loads picnicking at Kilcunda, followed the local sports, tramped the muddy streets to visit friends to play cards or to go to the pictures or attend the girls’ Scottish dancing contests.

The 1940s saw the start of a new era with Cliff widowed, his daughter housekeeping and a new generation introduced to Frog Hollow. Another bedroom and verandah were added to the front of the house after the war. The builder was Keith Kidd. Concrete paths and garden borders delineated areas and the advent of a car in the late 40s meant a garage/workshop was needed. The vegetable plots multiplied and a shower was installed in the washhouse for hot weather to wash off beach sand. A rotary clothesline sprang up in the back yard, the ‘lawn’ was rank grass and a worthy foe for the hand mower.

The `50s heralded a time of plenty: a refrigerator, the Namco washing machine in 1950, television in 1958, Sunday drives around the coast in the FJ Holden, organised sports on Saturday, Friday night pictures and Saturday matinees (“the flicks”). Fishing trips at night yielded garfish and flounder, rock-pool forays crayfish, the rock platforms sweep, leather-jackets and parroties.

Now the cottage was painted cream with maroon trim, the backyard roughly grassed with gravel ruts leading to the garage. A huge boobialla sheltered the back section where the netted fowl-run, fowl shed and pigeon loft filled the western corner.

Despite growing affluence, children’s pastimes in this era differed little from their parents’, depending on imagination and ingenuity: cubbies in the bush, “gangs”, home-made kites, bows and arrows, stilts, billycarts, treks to the Back Beach, mushrooming, blackberrying, jacks, skipping ropes, marbles, swap cards, pets. More bicycles extended the range of activities. Perhaps a pogo-stick, a scooter, a game of Monopoly or shuttlecock added a touch of sophistication. However, no matter how far they ranged, these kids of the `50s always returned home as it grew dark.

Now, in retirement, Cliff sought refuge from noisy grandchildren in the boiler shed, a warm, dark appendage to the house. Here he tended the donkey boiler, source of hot water. Soon, he had a separate bungalow built west of the house, a large light room where he had an open fireplace (later an oil heater), washbasin, beloved radio and books. He retired at night with a flask of tea to enjoy ABC radio in peace and comfort.

Swamp paperbark still pervaded the area in the 1960s, drains were open and deep, roads roughly remetalled from the mine stone dumps. Now the old wooden kitchen table and chairs gave way to tubular steel chairs with red leather upholstery and red laminex table, laminex benchtops, a cream painted kitchen with an aluminium hit-rail for chair backs. There were a large south-facing window, red-and-white patterned curtains, wall brackets to hold flowers and the red and white radio. The lounge, too, had undergone change. Out with the table, half-moon leadlight crystal cabinet, the original suite of two armchairs, three chairs and chaise longue (Blackwood and black old cloth), and the blackwood mantelpiece. All this was replaced by an oil heater, vinyl lounge suite and veneer buffet.

The yard was transformed. Lawns were developed, unfortunately with the new miracle grass, kikuyu, which certainly necessitated a motor mower (and which I am painstakingly rooting out by hand now). Native plants were established to complement the row of tree ferns planted in 1950 and the boobialla. There were paling fences, rockeries, tubs of plants, shrubbery and bright flowerbeds. A septic system meant a relocation of the lavatory from the back fence.

Thus the cottage had undergone great change from its 1915 inception: open fire to oil heaters, meat safe to refrigerator, copper to washing machine, coal stove to gad, copper heated water to donkey boiler, shank’s ponies and hand tools to car and power tools. Frog Hollow moved with the times.

Another watershed occurred in 1970 when Cliff died. From a three-generation household, it quickly became a one-generation home. Kitchen and bathroom were renovated when Wonthaggi was sewered, a hot-water system and freezer became modern necessities. Aluminium window frames, the lowering of the original lounge room ceiling, more concreting, a refurbished roof and new fencing followed. At 5am on Saturday, June 5, 1993, a freak storm hit Wonthaggi. The wind attacked from the west, reaching 145km/h. The barometer dropped to 974 millibars and temperature plummeted from 9.4˚c to 4˚c in five minutes. The middle front hit Frog Hollow, but the little cottage stood firm.

Today Frog Hollow huddles bravely against the bracing westerlies, facing its rutted red metal road on the town’s outskirts. Freshly painted, reroofed, all electric, it sits amid manicured lawns, pebble-mulched native garden beds and a large vegetable garden. Five generations have known this house; four have resided in it.

Its guardian gum, mature when Wonthaggi began, still protects with shelter and shade. It no longer houses koalas, but still harbours insects and an old possum, and is visited by a multitude of birds including crested shrike tits, spotted and striated thornbills, golden and rufous whistlers, silvereyes, brown thornbills, grey butcherbirds, magpies, black-faced cuckoo-shrikes …

Frog Hollow, a family home with history, weathers on.

This essay was first published in The Plod, the newsletter of the Wonthaggi Historical Society.

THE early days in Wonthaggi were tough with the bracing climate rolling in off Bass Strait, a regimen of back-breaking work in primitive conditions, the ever-present fear of the mine whistle heralding disaster and a time of intermittent strikes when miners fought for safe working conditions and security.

Cliff Gitsham needed to maintain a thriving vegetable garden and fowl yard, as well as become a fisherman and rabbiter, to provide for his family in strike times in the 1920s and especially the 1930s. Cupboards were always well provisioned to tide the family over in such events. Add to this the need to repair and extend the house, shedding and fences, and to keep up fuel supplies and there was little time left for relaxation. However, reading, woodturning local blackwood on a homemade bicycle lathe, and radio after 1930, filled in the gaps. Eva, too, had a heavy workload with washing nappies and pit clothes, preserving, baking, making clothes and rearing children, yet she enjoyed dancing, films, reading and crafts such as embroidery, crocheting, knitting and tatting. The crafts were done over morning tea as the neighbourhood women chatted, swapping recipes, cures and advice – their hands were never idle. It was here they traded produce and pickles, collecting milk from the local cow.

This neighbourhood was close-knit, with people helping each other with jobs and ready to share at all times, a feature of Wonthaggi’s staunch unionism. Workmates rallied in times of need and the tightly bound union town established the co-operative store – butcher, baker, grocer, haberdasher, ironmonger – (family account number: Gitsham G9), which provided help in times of strike and strife.

Although the Gitshams had no car before the war, the whole extended family enjoyed outings walking to the Back Beach a few miles away through the scrub. They joined the train-loads picnicking at Kilcunda, followed the local sports, tramped the muddy streets to visit friends to play cards or to go to the pictures or attend the girls’ Scottish dancing contests.

The 1940s saw the start of a new era with Cliff widowed, his daughter housekeeping and a new generation introduced to Frog Hollow. Another bedroom and verandah were added to the front of the house after the war. The builder was Keith Kidd. Concrete paths and garden borders delineated areas and the advent of a car in the late 40s meant a garage/workshop was needed. The vegetable plots multiplied and a shower was installed in the washhouse for hot weather to wash off beach sand. A rotary clothesline sprang up in the back yard, the ‘lawn’ was rank grass and a worthy foe for the hand mower.

The `50s heralded a time of plenty: a refrigerator, the Namco washing machine in 1950, television in 1958, Sunday drives around the coast in the FJ Holden, organised sports on Saturday, Friday night pictures and Saturday matinees (“the flicks”). Fishing trips at night yielded garfish and flounder, rock-pool forays crayfish, the rock platforms sweep, leather-jackets and parroties.

Now the cottage was painted cream with maroon trim, the backyard roughly grassed with gravel ruts leading to the garage. A huge boobialla sheltered the back section where the netted fowl-run, fowl shed and pigeon loft filled the western corner.

Despite growing affluence, children’s pastimes in this era differed little from their parents’, depending on imagination and ingenuity: cubbies in the bush, “gangs”, home-made kites, bows and arrows, stilts, billycarts, treks to the Back Beach, mushrooming, blackberrying, jacks, skipping ropes, marbles, swap cards, pets. More bicycles extended the range of activities. Perhaps a pogo-stick, a scooter, a game of Monopoly or shuttlecock added a touch of sophistication. However, no matter how far they ranged, these kids of the `50s always returned home as it grew dark.

Now, in retirement, Cliff sought refuge from noisy grandchildren in the boiler shed, a warm, dark appendage to the house. Here he tended the donkey boiler, source of hot water. Soon, he had a separate bungalow built west of the house, a large light room where he had an open fireplace (later an oil heater), washbasin, beloved radio and books. He retired at night with a flask of tea to enjoy ABC radio in peace and comfort.

Swamp paperbark still pervaded the area in the 1960s, drains were open and deep, roads roughly remetalled from the mine stone dumps. Now the old wooden kitchen table and chairs gave way to tubular steel chairs with red leather upholstery and red laminex table, laminex benchtops, a cream painted kitchen with an aluminium hit-rail for chair backs. There were a large south-facing window, red-and-white patterned curtains, wall brackets to hold flowers and the red and white radio. The lounge, too, had undergone change. Out with the table, half-moon leadlight crystal cabinet, the original suite of two armchairs, three chairs and chaise longue (Blackwood and black old cloth), and the blackwood mantelpiece. All this was replaced by an oil heater, vinyl lounge suite and veneer buffet.

The yard was transformed. Lawns were developed, unfortunately with the new miracle grass, kikuyu, which certainly necessitated a motor mower (and which I am painstakingly rooting out by hand now). Native plants were established to complement the row of tree ferns planted in 1950 and the boobialla. There were paling fences, rockeries, tubs of plants, shrubbery and bright flowerbeds. A septic system meant a relocation of the lavatory from the back fence.

Thus the cottage had undergone great change from its 1915 inception: open fire to oil heaters, meat safe to refrigerator, copper to washing machine, coal stove to gad, copper heated water to donkey boiler, shank’s ponies and hand tools to car and power tools. Frog Hollow moved with the times.

Another watershed occurred in 1970 when Cliff died. From a three-generation household, it quickly became a one-generation home. Kitchen and bathroom were renovated when Wonthaggi was sewered, a hot-water system and freezer became modern necessities. Aluminium window frames, the lowering of the original lounge room ceiling, more concreting, a refurbished roof and new fencing followed. At 5am on Saturday, June 5, 1993, a freak storm hit Wonthaggi. The wind attacked from the west, reaching 145km/h. The barometer dropped to 974 millibars and temperature plummeted from 9.4˚c to 4˚c in five minutes. The middle front hit Frog Hollow, but the little cottage stood firm.

Today Frog Hollow huddles bravely against the bracing westerlies, facing its rutted red metal road on the town’s outskirts. Freshly painted, reroofed, all electric, it sits amid manicured lawns, pebble-mulched native garden beds and a large vegetable garden. Five generations have known this house; four have resided in it.

Its guardian gum, mature when Wonthaggi began, still protects with shelter and shade. It no longer houses koalas, but still harbours insects and an old possum, and is visited by a multitude of birds including crested shrike tits, spotted and striated thornbills, golden and rufous whistlers, silvereyes, brown thornbills, grey butcherbirds, magpies, black-faced cuckoo-shrikes …

Frog Hollow, a family home with history, weathers on.

This essay was first published in The Plod, the newsletter of the Wonthaggi Historical Society.