His latest book is a lot more personal. A Sort of History of Me, My Family… And a Cow Named Gina tells the story of the Gatto family’s migration in 1951 from the village of Caridà, in the south of Italy, to the coal town of Wonthaggi. Much of the story is seen through the eyes of eight-year-old Sam, who, as the eldest child, is invested with great responsibilities to help his parents and siblings along the journey.

A Sort of History was shortlisted for the 2022 Victorian Community History Awards.

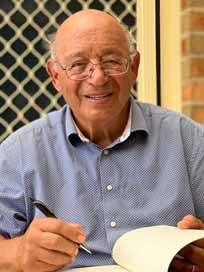

By Sam Gatto

In March 1952, Dad wrote to Zio Micuccio that he had a beautiful cow and calf, hens, ducks and ‘una bella iarda’, which he explained, since iarda is an Italianised version of the word ‘yard’, that has itself a special meaning in Australian English. What Dad really meant was a beautiful vegetable garden. An unmistakeable pride and achievement can be felt in his simple words. In fact, the whole quarter acre block in Broome Crescent was luxuriant with all sorts of vegetables, especially tomatoes and climbing beans. Gina was milking well too, partly thanks to the scifata, the gruel that Mum and Dad made by first washing all the pans, dishes and cutlery in just hot water and then adding pollard and bran, which was very cheap at the time, to the soup-like mixture. Gina loved it and she recompensed us with a plentiful supply of rich Jersey milk, so Mum and Dad could once again make their own cheese and ricotta. Except for meat, bread, oil and pasta, we were almost self-sufficient as far as food was concerned and would become even more so in years to come. In order to save money, and also because she didn’t like the bread supplied by the Co-op bakery, too white, too soft, too bland, Mum had tried to bake her own. She soon worked out that it was cheaper to buy bread than to make it yourself. And anyway, what she baked here did not taste the same as the wholesome bread made from her own wheat, ground in the traditional way at the local stone mill, and baked in the big oven under the house, fired by twigs and branches gathered in the local countryside, which infused the bread with a sweet aroma.

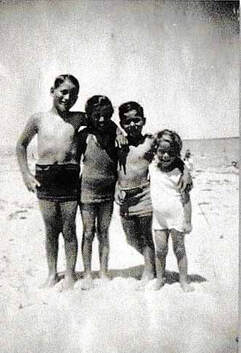

An early trip to Inverloch Beach, 1952. Sam, left, with siblings Mary, Peter and Tina. Photos were taken to send back to family in Italy.

An early trip to Inverloch Beach, 1952. Sam, left, with siblings Mary, Peter and Tina. Photos were taken to send back to family in Italy. Within a very short time the Gatto household in Broome Crescent had become a sort of meeting place for men from Caridà and its neighbouring villages. We were one of the first families from our region to migrate to Wonthaggi after the war; Mum was the only woman from Caridà until late in 1952, so on Sundays and public holidays our house was always full of paesani who would come for lunch or in the afternoon to play cards. It was a lot of work for Mum but, as I've said before, these occasions brought with them the sounds, smells and tastes of home, and she could express her sense of fun in this company. At the beginning of 1950 Zio Furci, always a good one for a laugh, and Cousin Lino, a calming influence, had joined Dad in Wonthaggi. In April 1951, Dad's brother, Uncle Jack, arrived and by the end of 1951 Michele Morfea had also arrived. When they got together with other paesani, there was not a dull moment. But Mum, except for Mrs Chiodo, had no female company, and she missed that terribly.

A House of Our Own

As far as I know, no member of either my mother's or my father's families had ever lived in rented accommodation. In fact, in Caridà, even poor people generally owned their own homes. Their house may have been only two rooms with no electricity or running water, with the barest of furnishings, but the roof over their heads was theirs, so Mum took it for granted that the lady who came each fortnight to collect the money they put aside each week was collecting instalments for the house that Dad was paying off.

From the first day she knocked on our door, Mum took a strong dislike to the heavily made-up, perfumed woman who, almost like clockwork, arrived on Saturday morning at 10 o'clock. Mum was always in a bad mood on Saturdays. It was the day when the house was cleaned from top to bottom, and she was always impatient to do the work thoroughly and quickly. We knew to keep out of her way... By the time the lady came, the house was spick and span. ·

One day the lady got on Mum’s nerves even more than usual. She confronted Dad and demanded to know how long that woman would be coming into her house, how much we still owed for the baracca, the shack, we were living in … It was then that Dad broke down and informed Mum that they were not paying the house off; they were renting it. What? Mum felt cheated, offended, let down. Dad was repentant, apologetic, pathetic in his explanations. Mum eventually pursed her lips. She would not be living in rented accommodation much longer, even if she was not here permanently, she let Dad know. We would have a house of our own. She may have been illiterate, but she knew the value of property and money and she knew that we could put the deposit together if we made a few more sacrifices.

In June 1952, a house of our own became a reality. Mum and Dad bought the house on two blocks at what was then 55 White Road, North Wonthaggi. With pride, in a letter dated 7 July, Dad wrote to Zio Micuccio and the rest of the family: apologizing for replying to his letter so belatedly, he explained that he had bought a house and, until he had settled everything, he had not had the time to write. In fact, they must have wondered what had happened, since Dad almost always replied to letters on the day he received them. He may have repeated the same phrases all the time, but this habit of his, which I wish I had inherited, meant that he kept in contact with many people.

The Gatto family and relatives in the garden at White Road, mid 50s.

The Gatto family and relatives in the garden at White Road, mid 50s. The weatherboard house, which still stands next door to the North Wonthaggi Kindergarten, had been built by the Ryan brothers most probably sometime in the late 1930s or early 1940s. Mr Joe Ryan had sold the house to an Italian acquaintance of Dad's, who, for some reason could not keep up the re-payments and so was forced to sell. This can probably partly explain the bargain that Dad got. The credit squeeze of 1952 which resulted in an increase in unemployment and a fall in house prices must also have played a role. The money Mum and Dad had been able to save in eighteen months was a substantial down payment in the circumstances.

At the time, there was a massive cypress hedge at the front and western side of the block, which meant that the house and garden were protected from the prevailing winds and got the benefit of the early morning sun. The gardener in Dad must have seen these advantages when he and I went to see the house for the first time. Mum also inspected the house before the contract was signed and, when she compared it to the house in Broome Crescent, she must also have been impressed, since I cannot remember any disagreement about it between Mum and Dad. The other advantage Dad must have seen was the many empty blocks in the area, where he could tether and graze his cows. He was also aware that he would be able to graze cows ‘on the long paddock’ for a very small fee. North Wonthaggi was then part of the Shire of Bass and, as a rural shire, it allowed residents to let their animals roam free and graze on the nature strips and empty blocks of Dudley, Hicksborough, Edgarton and North Wonthaggi. When we went to see the house, the grass was lush and green, which must have impressed Dad.

On the day of the move, Mr Nesci came in his truck and transported our few belongings to our new house. With Dad leading our two cows, both of which were in calf, Dad, my brother Peter and I walked through the town, along the thin strip of red stone footpath on the western side of McKenzie Street, under the canopy of tea-tree, past the stinking muddy drain, up the slight hill with the ‘Dog Course’ opposite, through the Country Roads Board tar depot just before the junction with White Road, crossed the rough gravel surface of White Road and there, opposite, was our new home, the house we grew up in.

It was a sad day for my mother when it was sold in the early 1970s, when Mum and Dad built their new house further up the road.