By John Wells

A talk given to the Wonthaggi and District Historical Society 54 years ago gives an invaluable insight into the lives of the early settlers.

On December 11 1962, W. P. Heslop was the guest speaker at the Wonthaggi and District Historical Society’s December dinner meeting. His talk gave many insights into the lives of the first settlers in the area.

A talk given to the Wonthaggi and District Historical Society 54 years ago gives an invaluable insight into the lives of the early settlers.

On December 11 1962, W. P. Heslop was the guest speaker at the Wonthaggi and District Historical Society’s December dinner meeting. His talk gave many insights into the lives of the first settlers in the area.

My version is a photocopy and it looks as if it came from one of the very first photocopiers and was originally typed on one of the first typewriters. It is on foolscap paper and we haven’t seen that for a long time.

I have one complaint, though, and that is that he doesn’t give much in the way of dates. If you ever write your own story, reader (and we should all do that), put in the dates!

Heslop was the son of Robert Heslop, who was born in 1860 in Rathfriland, County Down, in Northern Ireland, where there was constant and often violent unrest between Catholics and Protestants. He came to Melbourne in 1881, aged only 21. He set up as an auctioneer and estate agent and did well. He was soon a Preston Shire councillor.

He also married, his bride’s family coming from Nova Scotia to Melbourne in the early 1850s – but there is no mention of her name in this document. So there is another message, dear reader. When you write your story remember that your readers won’t know the things you take for granted.

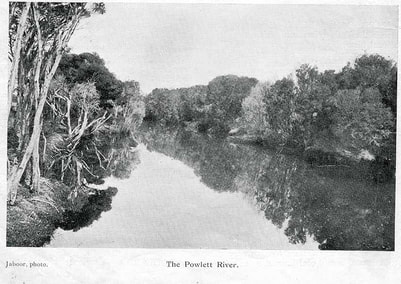

Robert took up The Run, 20,000 acres between the Powlett River and Inverloch. It was pretty poor country. Heslop described it as “Hungry and uninviting, heathy, scrubby country with speargrass plains and grass trees on the hillocks and was completely unfenced.”

Helped by Charlie Anderson and Thomas Martyn, two good men who worked with him for years, Heslop drove a mob of sheep down from Melbourne round the top of Western Port to The Run, not a bad effort in those days. He was clearly a man who enjoyed great success by “having a red-hot go”.

Anderson was a skilled carpenter and he was soon hard at work with Heslop building the collection of necessary sheds and a small homestead called Mayfield. This was about four miles (6.4 kilometres) north of Cape Paterson.

“Cooking was by camp ovens, suspended by hooks … over a very large open fireplace at one end of the kitchen-come-dining room, and it was not long before 17-20 had to be provided for during the shearing season …. Bread had to be baked in the camp ovens. Butter had to be churned by hand and all vegetables had to be grown on the spot. Lighting was by kerosene lamps or candles.”

Heslop doesn’t even talk about what happened once the wool left the sheep. It had to be baled and transported a long slow way before any money came back.

“There were the days of penny postage; a packet of cigarettes was 3d and elsewhere (for there were not any hotels nearby) a pint of beer was 3d. with a counter lunch thrown in. The top price realized for wool was 10d a pound.

“Transport was by horseback, or horse and jinker or buggy. We never saw rubber tyres until many years later. Heavy goods were moved by bullock wagon and stores were got in three months supply and came per boat ‘Ripple’ to Inverloch from whence they were collected by bullock wagon.”

I found it interesting that Heslop refers to Melbourne as the main shopping centre. He says that Leongatha and Korumburra were too small and not easily reached, which makes sense when you think about it. Not that Melbourne was too easily reached either. “The journeys (to Korumburra and Leongatha) were too arduous and Melbourne was the more easily reached centre, even though it meant an 18 mile trip by road to catch the 8.00am steamer from San Remo to Stony Point and then (the) train to Melbourne, arriving about 2.00pm.”

At some stage Heslop Senior acquired 340 acres on the Powlett, later named The Wattles. It was again a fairly primitive spot, with a ruined wattle and daub house, but a small two-roomed cottage that served while a new house was built.

“The hardwood for the house came from Kennedy’s saw mills on Kennedy’s Road off the Archies Creek Road and had to be brought from the mill by bullock wagon and across the Powlett River at the ‘slip’, a shelving slipway over the river between Tom Rileys’s and The Wattles. The bricks were from P.J. Daleys brick kiln at Bridge Creek …

“The Wattles became our main homestead, and an adjoining property ‘Orleigh Park” … with a frontage to the Powlett River was added. Clearing the land was arduous and heavy work and the handiest implement available was the Trewhella jack, plus muscle and brawn plus bullock teams to haul the logs together in heaps. Fires were going for weeks on end.

“Further additional farm buildings, stockyards, extensive stabling and chaff house, large hay shed, machinery sheds, slaughter house and yards and butcher’s shop were later added. Thus The Wattles became the main home property and Mayfield was utilized as an outstation, though mostly occupied by an overseer and one or other of the family, and when not so occupied the boundaries were ridden over, two or three times a week (a day’s job) from The Wattles.

“It only required more than one day of rain to make the roads impassable in the weak spots to even light vehicles, so that to be home-bound for days, other than on horse-back, was a not infrequent occurrence. Road metal was not available within the Shire. It was many years later before it was discovered and became available for everyday use.”

The rest of of Heslop’s story deals with the development and schools, hotels, famous people in the district and so forth, in a slightly disconnected manner, but an interesting one.

I said that he never gave us his mother’s name but I was somewhat wrong. She was Mary Gruber Heslop, who died in 1933. It is her maiden name I am missing, though, given the customs of the day that might have been Gruber. Robert Heslop died in 1920 and they are both buried in the Wonthaggi cemetery. That puts an end to that part of Heslop’s talk.

He went on to pick up on various things in Wonthaggi’s past, but just remember that there was no Wonthaggi until the State Coal Mine was established there in 1910.

There was a school at Bridge Creek but that was a bridge too far (sorry) and Heslop built a school nearby, rented from him and staffed by the Education Department. Heslop speaks highly of the school and its long-serving teacher, John Baker. He points out that with an enrolment of under twenty the school produced one member of parliament, two shire presidents, 2 Military Cross winners, one graduate of the Central Flying School at Point Cook in the Great War, one Colonel and one Doctor. When the coalfields were opened, of course, the school grew larger.

The family names of the early students included Kelly, Daly, Pinkerton, Cock, Hollole, Darling, Cadee, Jepson, Masters and Heslop.

The school Heslop is talking about was No. 3404 Powlett River, opened on Heslop’s on 7 November 1901. It was closed for a short time the following year, then worked half-time with Bridge Creek before going back to full-time in late 1902. The school struggled to maintain enrolments, with Dudley State School being only a mile away, but it survived until 1946.

State School 2722 Powlett River, opened in 1885. The name was changed to Wonthaggi in 1889. The school worked half-time with the Goodhurst State School (which was a new name to me) in 1893, and closed in 1896, all the furniture being taken to the Kilcunda school.

The Wonthaggi North school, No. 3203, became Glen Alvie and was a bit out of Heslop’s area. There was also a Wonthaggi school numbered 3715 opened in 1911 when the population was growing. This was called St Clair but became Lance Creek and was closed in 1965. The Hicksborough and Dudley schools were set up to serve the new mining communities.

The mail, and the newspapers, came in three times a week and there was a post office on the Powlett, which was at Heslop’s as one of its several locations. He speaks of young Jackie Dwyer, from San Remo, who brought the mail in on his pony, often having to swim his horse over the flooded river.

He speaks very briefly about the wreck of the Artisan. This was on 23 April 1902, at Cape Paterson. She was a barquentine of 1038 tons, with a crew of seventeen. She was blown ashore on a very high tide, partly built up by an onshore gale. When the tide ebbed the crew were able to walk ashore but the ship was too high on the rocks to be salvaged and the winter storms soon destroyed her. Captain Purdey was very ill and need medical assistance, but this was not a result of the stranding.

He talks of the local flora and fauna, noting that there were hares there long before there were rabbits, and quoting a cook hired for the shearing time who bolted when she saw a large goanna sliding down the kitchen window.

He also told the humorous story of Wonthaggi’s own Tantanoola Tiger. Some time in 1905 or not long thereafter there was a scare when very large tracks were found in the sand. Plaster casts sent to Le Souef, Director of the Zoological Gardens in Melbourne, were identified by him as being from a large carnivorous animal, though he couldn’t say which one.

“Many armed search parties were organized and finally the tracks were found in the sand leading to a small hillock covered with scrub, and then ending there. The tiger proved to be a innocent teddy bear, which when it ambles along overlaps the print of the front paw with the hind paw, thus producing a very large footprint on sand.”

“The nearest police station was at Inverloch and Mounted Constable John Kelleher was very popular, yet tactful and firm. At a local sports meeting one of the locals had imbibed and was argumentative and in a fighting mood, and so Constable Kelleher said to him “I’ll have to arrest you, Joe.” (Joe was not his real name). “Alright, John, but wait until I chuck this b(lighter) in the creek.” Heslop doesn’t tell us whether the Constable actually waited for that outcome.

He doesn’t say much about the development of the State Coal Mine and the Wonthaggi township, preferring to leave it to those with better memories. He does point out that the little satellite townships rather shrivelled on the vine when the big “tent city” was established. That is usually the case.

There had been much speculation and many subdivisions prepared, before the government announced the actual site, which it bought from John Hollins at £15 an acre, which seems rather a lot. The name Wonthaggi had been the parish name and was adopted for the new township, but I have never been able to establish where the name was first used or what it actually means, despite many efforts.

It was used for a local school in 1889 and that is the earliest use I know.

That is about the end of the Heslop talk for us, though there is more in this remarkably useful document. The Heslops were important and influential pioneers in the district and there is far more for us to know, but let’s just be grateful that W.P. Heslop was invited to speak to his local historical society in 1962 and that the notes of his talk have survived.

When I said you should write down your own story, I meant it. It is almost a duty. Papers like Heslop’s tell it the way it was, and only the people who lived it could tell it. That applies to your story, too. Only you can really tell it, and it is part of the collective history of all of us.

This essay was first published in the West Gippsland Trader.

I have one complaint, though, and that is that he doesn’t give much in the way of dates. If you ever write your own story, reader (and we should all do that), put in the dates!

Heslop was the son of Robert Heslop, who was born in 1860 in Rathfriland, County Down, in Northern Ireland, where there was constant and often violent unrest between Catholics and Protestants. He came to Melbourne in 1881, aged only 21. He set up as an auctioneer and estate agent and did well. He was soon a Preston Shire councillor.

He also married, his bride’s family coming from Nova Scotia to Melbourne in the early 1850s – but there is no mention of her name in this document. So there is another message, dear reader. When you write your story remember that your readers won’t know the things you take for granted.

Robert took up The Run, 20,000 acres between the Powlett River and Inverloch. It was pretty poor country. Heslop described it as “Hungry and uninviting, heathy, scrubby country with speargrass plains and grass trees on the hillocks and was completely unfenced.”

Helped by Charlie Anderson and Thomas Martyn, two good men who worked with him for years, Heslop drove a mob of sheep down from Melbourne round the top of Western Port to The Run, not a bad effort in those days. He was clearly a man who enjoyed great success by “having a red-hot go”.

Anderson was a skilled carpenter and he was soon hard at work with Heslop building the collection of necessary sheds and a small homestead called Mayfield. This was about four miles (6.4 kilometres) north of Cape Paterson.

“Cooking was by camp ovens, suspended by hooks … over a very large open fireplace at one end of the kitchen-come-dining room, and it was not long before 17-20 had to be provided for during the shearing season …. Bread had to be baked in the camp ovens. Butter had to be churned by hand and all vegetables had to be grown on the spot. Lighting was by kerosene lamps or candles.”

Heslop doesn’t even talk about what happened once the wool left the sheep. It had to be baled and transported a long slow way before any money came back.

“There were the days of penny postage; a packet of cigarettes was 3d and elsewhere (for there were not any hotels nearby) a pint of beer was 3d. with a counter lunch thrown in. The top price realized for wool was 10d a pound.

“Transport was by horseback, or horse and jinker or buggy. We never saw rubber tyres until many years later. Heavy goods were moved by bullock wagon and stores were got in three months supply and came per boat ‘Ripple’ to Inverloch from whence they were collected by bullock wagon.”

I found it interesting that Heslop refers to Melbourne as the main shopping centre. He says that Leongatha and Korumburra were too small and not easily reached, which makes sense when you think about it. Not that Melbourne was too easily reached either. “The journeys (to Korumburra and Leongatha) were too arduous and Melbourne was the more easily reached centre, even though it meant an 18 mile trip by road to catch the 8.00am steamer from San Remo to Stony Point and then (the) train to Melbourne, arriving about 2.00pm.”

At some stage Heslop Senior acquired 340 acres on the Powlett, later named The Wattles. It was again a fairly primitive spot, with a ruined wattle and daub house, but a small two-roomed cottage that served while a new house was built.

“The hardwood for the house came from Kennedy’s saw mills on Kennedy’s Road off the Archies Creek Road and had to be brought from the mill by bullock wagon and across the Powlett River at the ‘slip’, a shelving slipway over the river between Tom Rileys’s and The Wattles. The bricks were from P.J. Daleys brick kiln at Bridge Creek …

“The Wattles became our main homestead, and an adjoining property ‘Orleigh Park” … with a frontage to the Powlett River was added. Clearing the land was arduous and heavy work and the handiest implement available was the Trewhella jack, plus muscle and brawn plus bullock teams to haul the logs together in heaps. Fires were going for weeks on end.

“Further additional farm buildings, stockyards, extensive stabling and chaff house, large hay shed, machinery sheds, slaughter house and yards and butcher’s shop were later added. Thus The Wattles became the main home property and Mayfield was utilized as an outstation, though mostly occupied by an overseer and one or other of the family, and when not so occupied the boundaries were ridden over, two or three times a week (a day’s job) from The Wattles.

“It only required more than one day of rain to make the roads impassable in the weak spots to even light vehicles, so that to be home-bound for days, other than on horse-back, was a not infrequent occurrence. Road metal was not available within the Shire. It was many years later before it was discovered and became available for everyday use.”

The rest of of Heslop’s story deals with the development and schools, hotels, famous people in the district and so forth, in a slightly disconnected manner, but an interesting one.

I said that he never gave us his mother’s name but I was somewhat wrong. She was Mary Gruber Heslop, who died in 1933. It is her maiden name I am missing, though, given the customs of the day that might have been Gruber. Robert Heslop died in 1920 and they are both buried in the Wonthaggi cemetery. That puts an end to that part of Heslop’s talk.

He went on to pick up on various things in Wonthaggi’s past, but just remember that there was no Wonthaggi until the State Coal Mine was established there in 1910.

There was a school at Bridge Creek but that was a bridge too far (sorry) and Heslop built a school nearby, rented from him and staffed by the Education Department. Heslop speaks highly of the school and its long-serving teacher, John Baker. He points out that with an enrolment of under twenty the school produced one member of parliament, two shire presidents, 2 Military Cross winners, one graduate of the Central Flying School at Point Cook in the Great War, one Colonel and one Doctor. When the coalfields were opened, of course, the school grew larger.

The family names of the early students included Kelly, Daly, Pinkerton, Cock, Hollole, Darling, Cadee, Jepson, Masters and Heslop.

The school Heslop is talking about was No. 3404 Powlett River, opened on Heslop’s on 7 November 1901. It was closed for a short time the following year, then worked half-time with Bridge Creek before going back to full-time in late 1902. The school struggled to maintain enrolments, with Dudley State School being only a mile away, but it survived until 1946.

State School 2722 Powlett River, opened in 1885. The name was changed to Wonthaggi in 1889. The school worked half-time with the Goodhurst State School (which was a new name to me) in 1893, and closed in 1896, all the furniture being taken to the Kilcunda school.

The Wonthaggi North school, No. 3203, became Glen Alvie and was a bit out of Heslop’s area. There was also a Wonthaggi school numbered 3715 opened in 1911 when the population was growing. This was called St Clair but became Lance Creek and was closed in 1965. The Hicksborough and Dudley schools were set up to serve the new mining communities.

The mail, and the newspapers, came in three times a week and there was a post office on the Powlett, which was at Heslop’s as one of its several locations. He speaks of young Jackie Dwyer, from San Remo, who brought the mail in on his pony, often having to swim his horse over the flooded river.

He speaks very briefly about the wreck of the Artisan. This was on 23 April 1902, at Cape Paterson. She was a barquentine of 1038 tons, with a crew of seventeen. She was blown ashore on a very high tide, partly built up by an onshore gale. When the tide ebbed the crew were able to walk ashore but the ship was too high on the rocks to be salvaged and the winter storms soon destroyed her. Captain Purdey was very ill and need medical assistance, but this was not a result of the stranding.

He talks of the local flora and fauna, noting that there were hares there long before there were rabbits, and quoting a cook hired for the shearing time who bolted when she saw a large goanna sliding down the kitchen window.

He also told the humorous story of Wonthaggi’s own Tantanoola Tiger. Some time in 1905 or not long thereafter there was a scare when very large tracks were found in the sand. Plaster casts sent to Le Souef, Director of the Zoological Gardens in Melbourne, were identified by him as being from a large carnivorous animal, though he couldn’t say which one.

“Many armed search parties were organized and finally the tracks were found in the sand leading to a small hillock covered with scrub, and then ending there. The tiger proved to be a innocent teddy bear, which when it ambles along overlaps the print of the front paw with the hind paw, thus producing a very large footprint on sand.”

“The nearest police station was at Inverloch and Mounted Constable John Kelleher was very popular, yet tactful and firm. At a local sports meeting one of the locals had imbibed and was argumentative and in a fighting mood, and so Constable Kelleher said to him “I’ll have to arrest you, Joe.” (Joe was not his real name). “Alright, John, but wait until I chuck this b(lighter) in the creek.” Heslop doesn’t tell us whether the Constable actually waited for that outcome.

He doesn’t say much about the development of the State Coal Mine and the Wonthaggi township, preferring to leave it to those with better memories. He does point out that the little satellite townships rather shrivelled on the vine when the big “tent city” was established. That is usually the case.

There had been much speculation and many subdivisions prepared, before the government announced the actual site, which it bought from John Hollins at £15 an acre, which seems rather a lot. The name Wonthaggi had been the parish name and was adopted for the new township, but I have never been able to establish where the name was first used or what it actually means, despite many efforts.

It was used for a local school in 1889 and that is the earliest use I know.

That is about the end of the Heslop talk for us, though there is more in this remarkably useful document. The Heslops were important and influential pioneers in the district and there is far more for us to know, but let’s just be grateful that W.P. Heslop was invited to speak to his local historical society in 1962 and that the notes of his talk have survived.

When I said you should write down your own story, I meant it. It is almost a duty. Papers like Heslop’s tell it the way it was, and only the people who lived it could tell it. That applies to your story, too. Only you can really tell it, and it is part of the collective history of all of us.

This essay was first published in the West Gippsland Trader.